This year’s Met Gala saw many of its high-profile attendees looking like cyborgs as its theme, Manus x Machina, commented on the growing influence of tech on the fashion world. But the impact of electronic media and technology on contemporary life is also being reflected in the art world. Over the past few years there has been a growing trend of artists experimenting with humanoid creations and more often than not, the result is nightmare-fuel.

We rounded up six of the most disturbing humanoids sighted in the art world recently.

1. Colored Sculpture (2016), Jordan Wolfson.

Jordan Wolfson, Colored sculpture (2016). Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ and David Zwirner.

At the top of the list is Jordan Wolfson’s latest installation: Coloured Sculpture, which is currently on show at David Zwirner’s Chelsea Gallery. An enormous red-haired animatronic puppet is chained to the center of the gallery. Equipped with motion sensors, its creepy eyes follow you around the room but its gap-toothed grimace is no Mona Lisa smile. Over the course of 20 minutes the chains winch in and out, manipulating the marionette, sometimes twisting its limbs in a manner that recalls ancient torture techniques, other times roughly slamming the puppet to the ground and dragging it across the floor in a violent frenzy. Occasionally, the chains relax and the humanoid collapses. As it hangs limply, eyes rolling about the room, it emanates a deep monotone, listing alternately gentle and terrible thoughts about someone… the spectators perhaps? The installation becomes particularly lurid when it croons Percy Sledge’s 1966 When a Man Loves a Woman, which marks the cue for the apparatus to transition from stillness to attacking the puppet with renewed intensity. Colored Sculpture is the sequel to Wolfson’s dancer robot, Female Figure, which caused a furor in 2014.

2. Female Figure (2014), Jordan Wolfson.

Jordan Wolfson’s animatronic sculpture at David Zwirner. Photo: Rozalia Jovanovic.

Not unlike Wolfson’s polarizing videos that draw you in just to spit you back out, Female Figure is simultaneously seductive and repulsive. With flowing blonde locks and clad in thigh-high leather boots and a white leotard that could put Miley Cyrus to shame, the robot dances sensuously to pop music and, because she is equipped with facial-recognition technology, makes unnerving eye-contact with her spectators. The upbeat tunes are occasionally punctuated by a male voice (Wolfson’s), a jarring interruption of the robot’s femininity, that proclaims “My mother’s dead. My Father’s dead. I’m gay. I’d like to be a poet. This is my house.” The spectator’s sense of unease is heightened by the fact that most of her face is obscured by a witch mask and, on close inspection, her body is covered in dirty smears. The piece was so unbelievably odd that it inspired artists Jen Catron and Paul Outlaw to send artnet News a mini-sexy robot for your desk, a parody of Wolfson’s bot complete with wind-up gyration. After a six-week run (again, at Zwirner’s Chelsea gallery) Female Figure was snapped up by mega-collectors Eli and Edyth Broad.

Perhaps the most disturbing element of both Wolfson’s pieces is the eyes. The conspicuous installations invite spectators (we couldn’t tear our eyes away if we tried) but the animated eyes challenge that spectacle by reflecting the gaze straight back to the spectator.

3. Untitled (2014), Andro Wekua.

Andro Wekua, installation view at Kölnischer Kunstverein 2016. Photo: Simon Vogel.

Andro Wekua’s debut show at Sprüth Magers in 2014, mystifyingly entitled Some Pheasants in Singularity, featured another uncanny humanoid. The untitled centerpiece of the show was the life-size figure of a young woman. The blonde girl, sporting a short black mesh dress and silver tennis shoes floats, ghost-like, just above the floor. But she is no spirit, she is a cyborg; one of her arms is encased in a robotic prosthesis and the other, adorned only with a sweatband, thrums against her bare thigh. Her chin rests upon a rectangle of reflective glass suspended horizontally from the ceiling, which simultaneously recalls both a childhood swing and a hangman’s noose. The eerie pallor of her face, her almost peacefully closed lids and the rhythmic thrumming of her fingers against her bare legs would almost be erotic if it weren’t so distressing. Connected by black wires to the source of her movement, a conspicuous black box, she makes a hair-raising sight. She is currently on view at the Kunstverein in Cologne.

4. To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll (2016), Goshka Macuga.

Goshka Macuga, To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll, (2016). Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani Studio. Courtesy Fondazione Prada

Perched on the edge of a stage at Prada Foundation wearing a transparent PVC jacket, sits Goshka Macuga’s bearded android. Created by A-Lab in Japan, he blinks, moves his hands, and turns his head as he rehearses a monologue pieced together from excerpts of history’s greatest orations. Surrounded by a cosmos of great art from around the world that suggests a history museum rather than a contemporary institution, he is a repository of human speech for a post-human world. Like Wolfson’s installations, Macuga’s man-made man is both alluring and repellent, for though he may spout the wisdom of ages, he suggests a somewhat dystopic future where this wisdom is manipulated into demagoguery bereft of meaning.

A fascinating take on post-humanity, Goshka Macuga’s show “To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll” is exhibiting until 19 June at Prada Foundation.

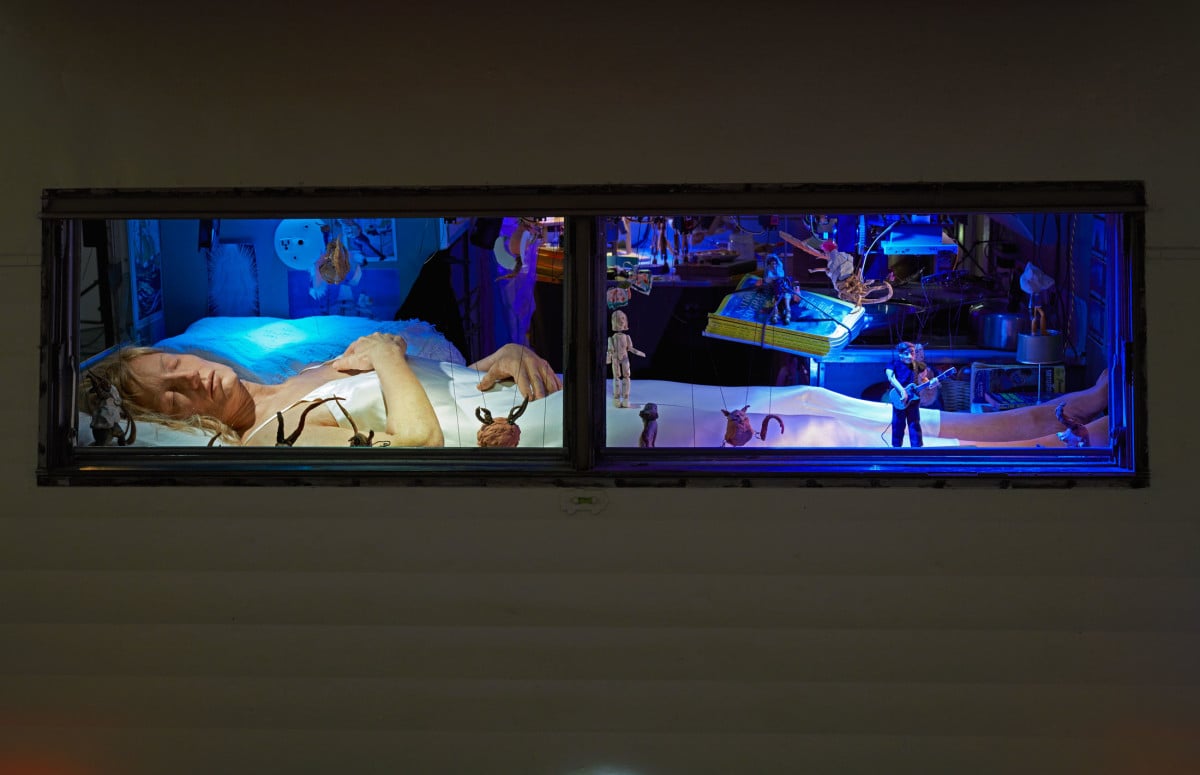

5. The Marionette Maker (2014), Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller.

Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, The Marionette Maker (2014). Image: ©Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller; Courtesy of the artists, Luhring Augustine, New York, and Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid.

Next in our lineup is Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s The Marionette Maker, which exhibited at Luhring Augustine in 2014. An 11-foot caravan is parked in a darkened gallery. Perched atop the isolated trailer sit giant megaphones: from one side, a tiny opera singer and pianist burst into song, from another, a looping soundscape of animal calls fades into thunderclaps and the patter of rain on a tin roof. If you peer into the window you see a tiny robot-controlled puppet show suspended over a life-size wax figure of a woman sleeping in a white slip. The marionettes, which range from a tiny fidgeting sketch artist at a desk to bulbous, anthropomorphic globs of clay, bounce up and down above her, raising the question of who is in fact pulling the strings. Did the sleeping woman (who bears an uncanny resemblance to Cardiff) dream the scene or is the little puppet toiling at his desk the true architect? It’s enough to make anyone jittery.

6. OMOH (2014), Julius von Bismarck.

Julius von Bismarck, OMOH, 2014. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Finally, if you weren’t creeped out enough, Julius von Bismarck brings us yet more humanoids. In OMOH, a battalion of uniformed police officers stand in intimidating formation. Individually, and almost imperceptibly, their bodies fidget. A shoulder moves here, a hand twitches there, and occasionally one shifts its weight from one foot to the other. At first they seem lifelike: restless soldiers trying their best to remain still. Up close, however, you notice the repetition of some of the movements that tells you which figures are disguised humans and which are mindless automata. At the Winzavod Center for Contemporary Art in Moscow, the figures were clad in the military uniform of the OMOH, a special police unit. When exhibited at Kunst-Werke in Berlin, they were outfitted in the uniforms and gear of the German riot polizei. Chilling.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.