Art World

Why the Slaughterhouse Became a Powerful and Enduring Motif in Art

Contemporary artists Aria Dean, Mire Lee, and Kat Lyons are exploring the subject in their work.

Contemporary artists Aria Dean, Mire Lee, and Kat Lyons are exploring the subject in their work.

Emily Steer

The abattoir has been an ongoing concern for artists since its inception, from Lovis Corinth’s 1893 painting In the Slaughter House, to Chaim Soutine’s gristly Carcass of Beef (1925). Aria Dean’s installation at London’s ICA (on view until May 5), is yet another urgent look at the subject. While the wider world grapples with the ethics of meat production and its resulting destruction on the environment, many artists use the slaughterhouse as an analogy for something deeply rooted in political and social life: namely, what can humans’ ability to disregard industrialized death on such a vast scale tell us about other violent and exploitative structures?

Dean’s “Abattoir”—the American artist’s first institutional show in the U.K.—takes viewers on an animated journey through an empty slaughterhouse that references historic architecture spanning the 1800s to modern times. The project explores the intertwined nature of death and modernity, questioning the role of similar systems to which humans are subjected, such as the private prisons of North America and the dynamics of settler colonialism.

“The slaughterhouse is a space where humans, animals, and machines all come together repeatedly in this horrible choreography,” said Dean, speaking in an interview ahead of the exhibition opening in London. “The history of the slaughterhouse is tied up in economic models; Fordism comes out of the process of animal slaughter after Henry Ford saw it as a great way to arrange a factory.”

Aria Dean Abattoir. Courtesy ICA

The video piece, called Abattoir, U.S.A.!, reflects just how embedded processes of killing are in much of the contemporary world. Dean examines the slaughterhouse as the root of modernist design, where form follows function. “If there was anything I was trying to get to, or a thesis that the research process was trying to prove or give weight, it was that rather than suppose life affirming or socialist utopian threads of modernism, there is also this necro political death and killing that is deeply implicated, even architecturally,” she said. “We have generated entire systems of thought around architecture through the slaughterhouse.”

The visibility or opacity of systemic violence is woven throughout Dean’s piece. For a start, viewers see inside a space that many will never visit in reality. Dean built her abattoir using 3D-computer graphics tool Unreal Engine without entering a slaughterhouse herself, instead basing the design on digital footage from both the meat industry and animal rights activists. She sees this distant viewing of violent material as being inherently connected with the subject of industrialized death. Dean also suggests similarities with the current online viewing of deeply traumatic imagery from Israel’s war on Gaza. “For a long time, I’ve been interested in the circulation of violent imagery,” she said. “The question of evidence, and that we want to see things; that everyone needs to see these things. It’s as though knowing would change people’s mind. But it’s possible that people don’t really care. At some point it becomes gluttonous or libidinal to watch this violence.”

Dean has previously shown Abattoir, U.S.A.! in Chicago, where parallels were drawn with the city’s meat-packing history, and in Toronto, at the Power Plant, where viewers commented on its connection with the prison system. She leaves the work open to interpretation, inviting comparisons with oppressive structures around the world that conceal or deny their violent intent even to those suffering under them. “In my view, pretty much everything is modelled in this way; a killing machine that makes you feel like it’s okay. There are very few spaces in our world now that aren’t designed in that way.”

Exhibition view of “Mire Lee: Black Sun” at the New Museum until September 17, 2023. Photo: Dario Lasagni, courtesy New Museum.

Dean is not the only artist who has taken up this subject. Mire Lee, who was recently named for the Tate’s prestigious annual Turbine Hall commission, also conjures the sinister depths of the slaughterhouse. In the South Korean artist’s work, strips recalling organic masses are often hanging from industrial forms. In these future-facing sculptures, the body is torn apart, ending up as nondescript lumps. All living beings become the same matter in Lee’s work, stripped of personality, individuality, and vitality—inferior to the technology around them. Often shown within cavernous art spaces (from the grimy bricks of the Arsenale in the Venice Biennale’s 2022 “Milk of Dreams” exhibition to New Museum’s darkened cube for 2023 solo “Black Sun”) her works mirror the abattoir’s cold meeting of metal and flesh, dripping with viscous liquid waste. The Turbine Hall’s industrial scale is sure to be a suitable setting.

Similarly, Giulia Cenci, who was also included in the 2022 Venice Biennale, places disembodied forms and twisted flesh within industrial settings. For Alemani’s exhibition, she filled a 150-metre alleyway in the Arsenale with hanging sculptures inspired by agricultural equipment. The Italian artist lives on a farm, with her studio in a former slaughterhouse, and there is often a sense of claustrophobic containment in her works as the body becomes trapped within cage-like structures.

In Goldsmiths CCA’s 2023 exhibition “Unruly Bodies,” Cenci hung corporeal forms in states of decay and dismemberment within steely boxes. The hybrids of human, animal, and alien evoked the cold manner in which specimens might be viewed in a lab, ignoring the pain endured by the living creature that ended up in this state.

Kat Lyons in her studio, 2023. Photo: Reggie McCafferty

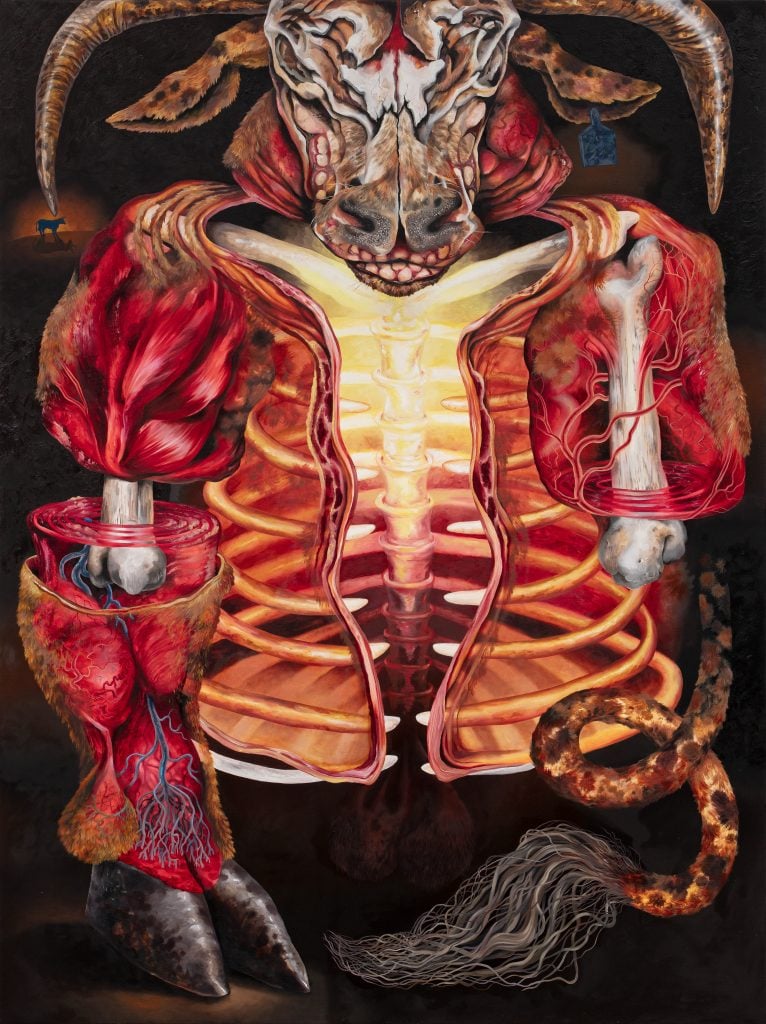

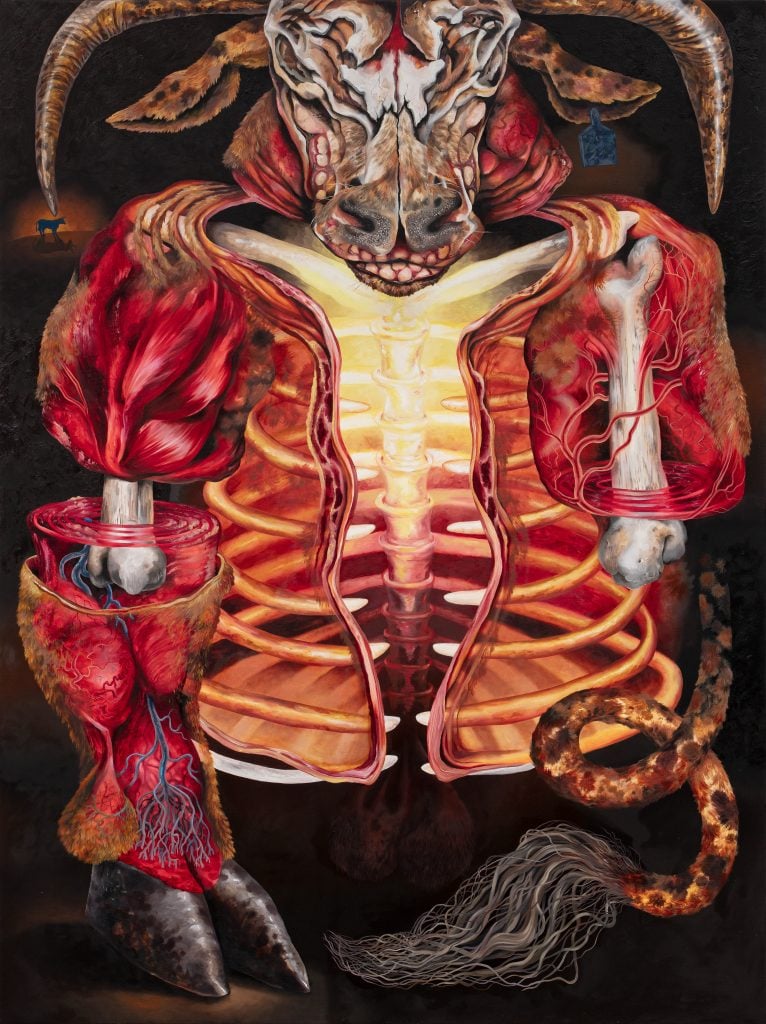

Kat Lyons’s intense paintings depict the death and dissection of farm animals with visceral gore. “We are now understanding that human histories are inextricably intertwined with non-human histories,” the American artist said in an interview ahead of her exhibition “Herd,” which opens at Pilar Corrias in London on March 8 (on view until April 6). “I am thinking about the topic of human advancement, at the helm of non-human participation—whether it’s symbolic or exploitative in nature.”

There is both horror and beauty in her paintings, as she pores over animals’ body parts, exposed organs, and mouths agape in terror. She has worked on various small farms in America and been present for slaughters; this has also given her an in-depth knowledge of the pressures on independent farms from bigger organizations. She is committed to taking a non-sentimental view of farming, visualizing a violent system that reflects broader human labor concerns.

The small piece of lamb, 1927 (oil on canvas). Chaim Soutine. (Photo by Apic/Bridgeman via Getty Images)

“The slaughterhouse operates in secrecy,” said Lyons. “Because the animal experience is largely ignored, it is easier for the human labor in these places to also be exploited. Since the industrial revolution, there have been terrible conditions; it’s still an issue. You think of migrant workers on the floor who have very little voice or rights. And then the animals’ labor is barely considered, because they are seen as products or secondary participants within a machinery system. These issues are ripest in the slaughterhouse.”

Lyons takes viewers inside not just the abattoir but also into the body, painting transparent layers that reveal the inner workings of her creatures. She reignites the disgust of cutting open a body that many people have become numbed to when viewing and eating packaged meat. “There is a literal dissection that happens, but there is also an attempt to dissect our conception of animals, to defamiliarize our relationship with them,” she said.

While Lyons’ works could be read on a literal level, like many artists who explore the slaughterhouse, she is more focused on the framework that underpins our ability to treat creatures in this way. She questions which deaths we deem to be allowable, and the hierarchies that we apply between animals as product or pet. A world that makes such categorizations possible allows for similar detachment from and classification of humans. “The slaughterhouse is a mirror of the human condition that we allow to be in practice in our daily lives,” she considered. “How can we deal with human structures and hierarchies without looking at those which are considered to be the lowest, or even product?”