Museums & Institutions

Smithsonian Museum Debuts Online Portal of Newly Acquired Slavery Artifacts

The museum acquired the collection, the largest and most complete set of Charleston slave badges, in 2022.

The museum acquired the collection, the largest and most complete set of Charleston slave badges, in 2022.

Adam Schrader

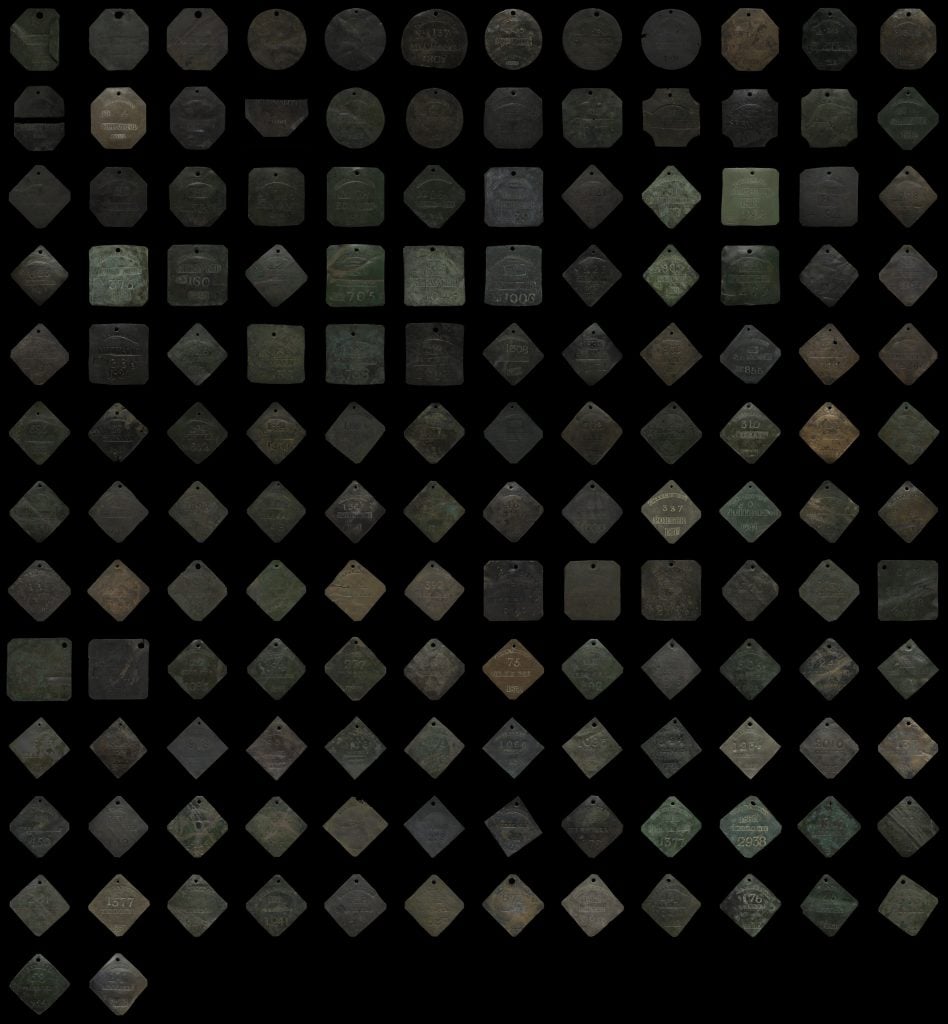

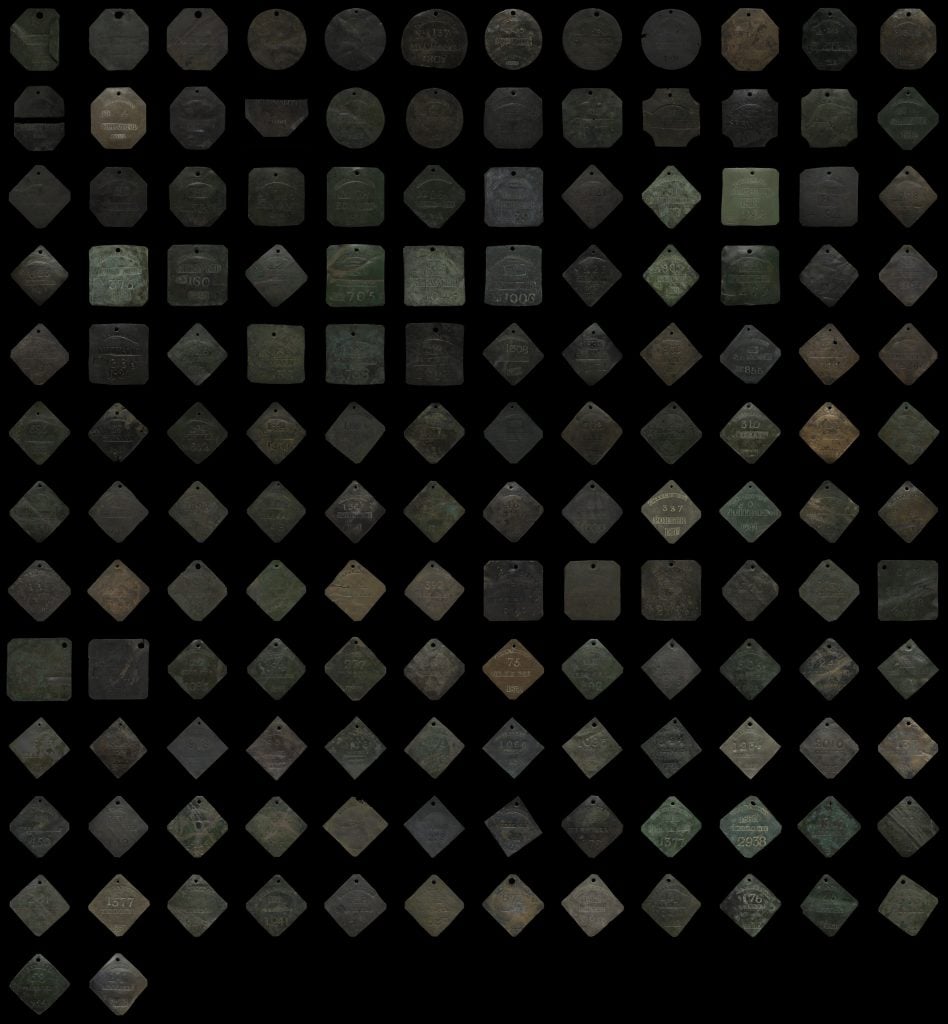

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture has launched an online portal featuring 146 slave badges from Charleston, South Carolina, that it acquired in 2022.

The collection is considered the largest and most complete set of Charleston enslavement badges, which were tags that were historically used to identify and classify enslaved people. Two of the badges have personalized inscriptions.

The slave badges in the collection date back to 1804, shortly after the city enacted two laws in 1783 and 1786 that required enslavers to register their enslaved people with the government and that enslaved people wore badges with their name and skills, such as whether they were adept in mechanics or carpentry.

Charleston slave badge for Fisher No. 14 (1800). Photo courtesy of Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Enslavers often rented out the labor of their slaves to increase their profits. The badge system was created to track the ownership of enslaved people as the practice of renting out labor grew. Free Black people were later required to wear badges indicating their statuses.

The online tool provides images and the history of the tags in context with the museum’s other artifacts. For example, the museum’s collection includes the hiring agreement for the rented labor of an enslaved woman named Martha in 1858.

“We are honored to share the story of enslaved African Americans who contributed to building the nation,” said curator Mary Elliott. “It is a story that involves the juxtaposition of profit and power versus the human cost. The story sheds light on human suffering and the power of the human spirit of skilled craftspeople.”

Charleston slave badge for Servant No. 855 (1832). Photo courtesy of Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The collection was compiled by Harry S. Hutchins Jr., a dentist in Charleston recognized for his “impressive probing” of the slave-for-hire system in South Carolina with fellow researcher Harlan Greene. Together with co-author Brian E. Hutchins, the pair wrote and published a book on slave badges highly regarded by collectors.

“Hutchins dedicated his life to collecting slave badges, expressing that he felt it was important to tell the story of the skilled craftspeople,” the museum said in a statement. “When presented with the opportunity to draft the credit line for the collection, Hutchins provided the following text ‘Partial Gift of Harry S. Hutchins, Jr. DDS, Col. (Ret.) and his Family, dedicated to the individuals these Slave Hire Badges represent and their descendants.’”