People

‘You’re Present for All of It’: Artists Open Up About Centering Sobriety in Their Creative Practices—and How It Changed Their Lives

"Sobriety means that you can have a great work ethic and wake up when the sun rises."

"Sobriety means that you can have a great work ethic and wake up when the sun rises."

Katherine McMahon

For centuries, alcohol and drugs have been romanticized in the art world, often glorified as catalysts for creativity and altered forms of consciousness. From Henri Toulouse-Lautrec’s appreciation for absinthe to Jean-Michel Basquiat’s deathly struggle with drug use—anecdotes about addiction contribute to the lore surrounding some of the greatest artists in history and how they created their masterpieces. But many times, loosely factual stories reinforce these narratives that aren’t always entirely true, effectively glamorizing something that simply didn’t happen.

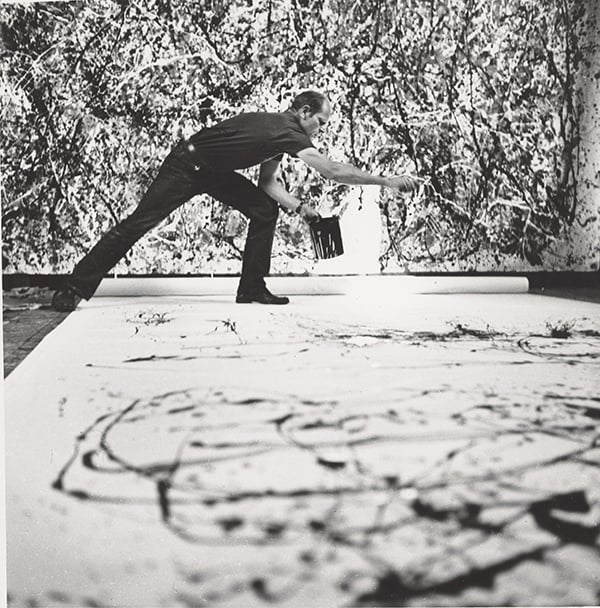

“The mythologized story that Jackson Pollock painted while drinking and listening to jazz music is nonsense. There was no radio or record player in the studio; he didn’t listen to music in the studio at all,” Helen Harrison, director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, told me. “Jackson didn’t drink when he painted. He drank instead of painting, and that was the problem.”

In the late 1940s, Pollock, who was sober for two years while under the care of a local physician, was at his most productive and innovative. “That was the period when he really came into his own as a creative innovator,” said Harrison. “When he returned to drinking in the winter of 1950–51 and tried a number of different strategies to get sober (none of which worked), his production declined significantly.”

Hans Namuth, Jackson Pollock at work in 1950. Photo: ©1991 Hans Namuth Estate, Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, the University of Arizona.

The overindulgence of the Abstract Expressionists is perhaps notorious. As Elaine de Kooning, artist and wife of Willem, recalled in the 1993 hardcover Elaine & Bill: Portrait of a Marriage: “We just began to drink and around 1950 everyone just got drunk and the whole art world went on a long, long bender. And what happened is that we turned into alcoholics.”

“That generation seemed to be rarely sober,” artist Eric Fischl told me.

Fischl originally moved to New York City in 1978 and was part of the class of artists following the Abstract Expressionists, who he described as “super drinkers.” His own story of sobriety began in 1987, days after his show at the Whitney Museum, which he told me he was “incredibly drunk and stoned for.” Preceding Fischl’s decision to get sober, he said, was a fear “that I wouldn’t be funny anymore.”

Many artists I spoke with elicited similar feelings of anxiety about navigating the social side of the art world while sober. Recalling a conversation with the late New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl, who had been sober for almost 30 years at the time of his death in October 2022, Fischl added: “He said the thing about stopping drinking is that you gain your mornings, but you lose your nights.”

Caravaggio, Bacchus (ca. 1595). Collection of the Uffizi, Florence.

Depending on who I spoke with, the definition of sobriety varied. Some individuals defined sobriety as consuming no mind-altering substances of any kind, while others believe concessions can and should be made for prescribed substances such as Adderall or medical marijuana.

Meanwhile, the “sober curious” lifestyle, which promotes sobriety as a choice and not necessarily a need, is burgeoning—being discussed openly on social media (the hashtag #sobercurious has garnered more than 300 million views on TikTok), with the non-alcoholic drink industry growing more than 120 percent over the last three years.

Sobriety can exist as a unifying common goal, yet the individual’s pursuit of sobriety is multifaceted and deeply rooted in personal experience.

Hilde Lynn Helphenstein, curator, artist, and creator of @Jerrygogosian on Instagram, got sober at the age of 33. “I think I romanticized [drinking] very early on and I definitely thought that it helped with creativity,” she said. “I didn’t know that that pursuit would come with a lot of misery.”

She added: “When you wake up from a blackout, you’ve spent money and you don’t feel like getting up and making art. You waste time, you waste money. You start to see other people getting success and when you’re not one of them, you don’t understand why.”

Helphenstein’s decision to get sober came shortly after she launched her popular meme account. “I felt like all of a sudden I had this project worth living for and I knew that if I kept drinking, I would never live to see what came of it,” she said. “When you stop dulling all the synapses in your brain, your thoughts are actually way wilder, way more fun, and kind of scarier—and you’re present for all of it.”

Brad Phillips, Clock for Drunks (2022). Photo courtesy of De Boer Gallery.

New York City- and Toronto-based artist and writer Brad Phillips, who explores themes of mental illness and addiction in his realistic depictions of fragmented life experiences, similarly debunked the idea that substances could serve as creative fuel.

“So much of addiction is just being uncomfortable with reality and wanting to change it,” Phillips told me. “There’s this romantic nostalgia for this idea that we were more creative when we were using. But when I look back at it, it was a shit show. When you’re an addict and you’re using, you may be in your studio but you’re really still just thinking about getting high, being high, or coming down from the high.”

When Phillips decided to get sober, one of the issues he contended with was how his identity felt intrinsically tied to his addiction. “It was hard to imagine what it would be like to be sober. But really, it’s just everything is the same but there’s less drama and less shit to contend with.”

Today, Phillips sees his studio practice and artistic life as something to be supremely grateful for as much as a job. “Being sober is all about accepting life on life’s terms. It’s also about accepting yourself and accepting external factors,” he told me. He also emphasized the importance of enabling other artists, as they struggle with alcohol, to see that sobriety is possible: “It’s important to talk about things that people find stigmatizing.”

Willem Claesz. Heda, Still life with a roemer on a gilt stand, stoneware and oysters (1637). Photo: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images via Getty Images.

As for New York-based painter and writer Walter Robinson, who’s been sober since 1990, drinking felt ubiquitous with everything, not just art-making. “Did I drink for inspiration? Sure. But then I drank for everything. I drank to wake up, to go to sleep, to get to work, to make a phone call, to be more sociable, to relax…” he recalled. “Any reason was an excuse to drink.”

Robinson spoke of the therapeutic value of the 12-step program, and how that journey paved the way for a vague sense of confidence in himself and his creative instincts. “Drinking is often a search for a magical elixir that will transform you into what you want to be—and sometimes I think that confidence is all you need,” he told me. “Now that I don’t drink, I don’t miss it at all. I’m 72 though, and I do miss being young. A little.”

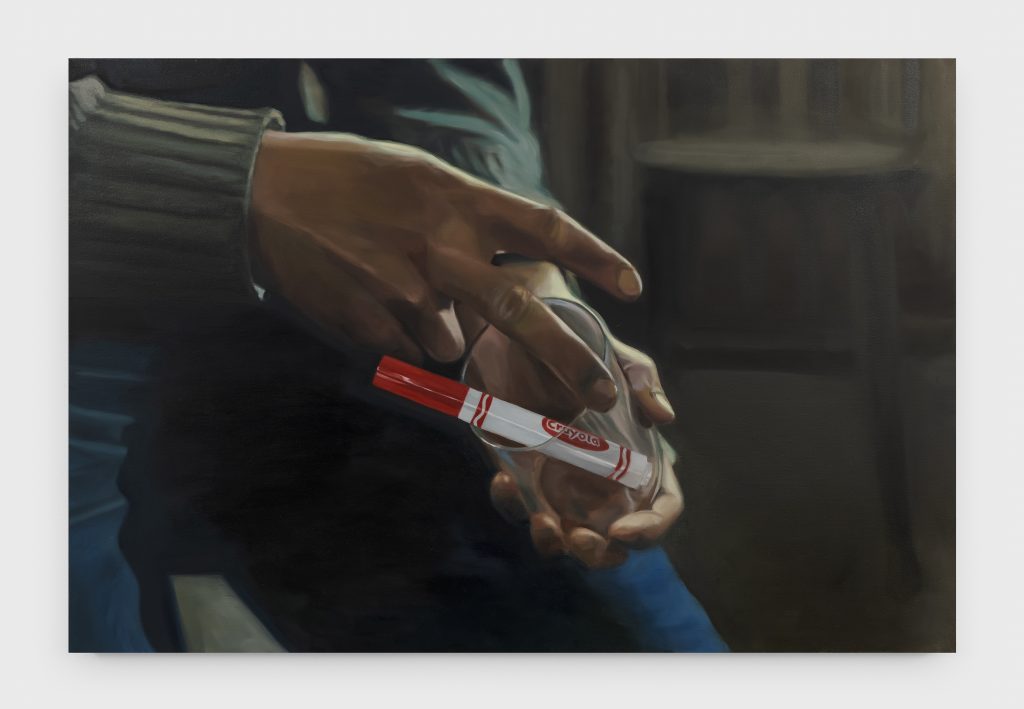

Shannon Cartier Lucy, Red Crayola (2022). Photo courtesy of Night Gallery.

Nashville-based painter Shannon Cartier Lucy, who has been sober for 16 years, recalled an encounter on the New York City subway during one of her early attempts at kicking her heroin addiction.

“I told this woman that I was an artist and I was in the process of trying to get clean. And without missing a beat, she just said, ‘ugh, sobriety kills creativity!'” she said. “I was so vulnerable at that time that it struck me so deeply. I went home with the heaviest heart and thought, ‘well, goodbye art!’ I put my trust in anyone but myself at that time and I believed her 1,000 percent.”

Lucy left New York City and moved back to her hometown of Nashville at the age of 30, and didn’t paint for 10 years—until suddenly, something clicked. “It was like a deluge,” she remembered of the turning point. “I was painting like crazy and I’ve never felt so connected to my work.”

That 10-year hiatus, where Cartier focused on healing—going to Narcotics Anonymous and Alcoholic Anonymous meetings, and getting a masters degree with the plan of becoming a psychologist—proved to all be part of the creative process.

“Looking back, I wouldn’t trade the experience because I managed to find footing on that shaky ground,” she said, adding that it’s the sobriety but also the calmness and maturity derived from life experience that ushered in this new chapter of her life as a creator.

“I used to think I had to be living in pain to express that pain, which I now think is absolute garbage,” she emphasized. “Because I have sobriety and I’ve done this kind of work, I’m able to have a view on the pain and the mystery versus drowning within it. Sobriety also means that you can have a great work ethic and wake up when the sun rises.”

On February 18, 2023, Cartier Lucy’s solo show, “Rubedo” opened at Night Gallery in Los Angeles. The title of the show, meaning “redness,” is a nod to a stage in Jungian psychological framework that a person undertakes toward individuation. The paintings, loosely guided by the theme while incorporating the idea of destruction and reconstruction, are lush yet slightly ominous.

“I have a sense of trust when it’s right. The ‘feel right’ to me has a slight discomfort and mystery to it, sort of like when you watch a documentary about black holes,” she said. “With my work, it’s only when I’m truly personal and telling the truth from that core place that I think I can relate to other people on a personal level.”

As it turns out, that woman on the train was wrong.