On View

‘This Flag Brought Our Nation Back Together’: Artist Sonya Clark Explains Why She Is Recreating the Little-Known Flag That Ended the Civil War

Can the Confederate truce flag replace its battle flag in the American imagination?

Can the Confederate truce flag replace its battle flag in the American imagination?

Sarah Cascone

Sonya Clark wants to put the Confederate flag on display. No, not the controversial Stars and Bars, a symbol of slavery that is still embraced in parts of the Southern United States. Clark is instead showcasing a different flag flown by the Confederacy during the Civil War: the one they used to surrender. The little-known flag is at the center of her new exhibition at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia.

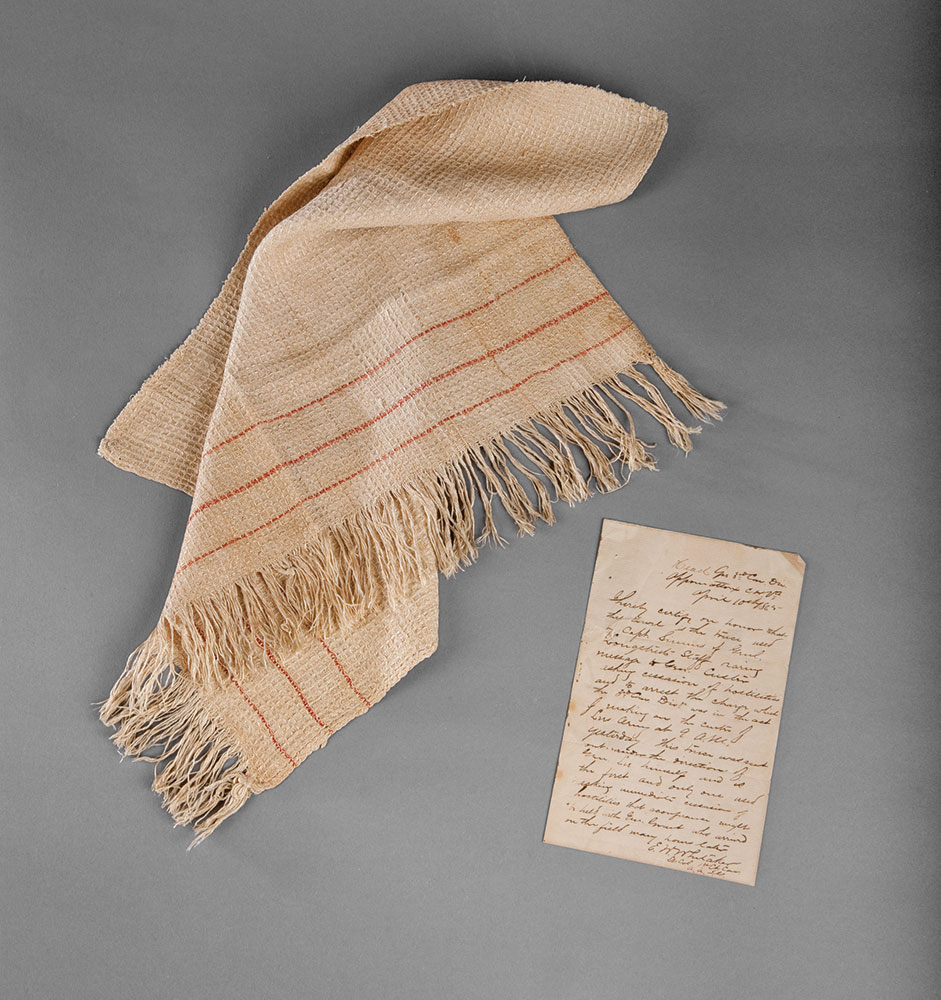

The flag of truce’s history dates back to April 9, 1864, when Confederate General Robert E. Lee sent forth a rider waving it, putting an end to the long and deadly Civil War. Union General Ulysses S. Grant accepted the Confederacy’s surrender and cut the flag in half so that the rider, who had purchased the repurposed dishtowel just days before in Richmond, Virginia, could ensure safe passage back across Union lines.

The other half of the flag was given to Elizabeth Custer, wife of General George Armstrong Custer, who donated it to the Smithsonian Institution in 1936.

That’s where Clark first encountered it by chance in 2011, when she was wandering the National Museum of American History in Washington, DC. “This is the flag that brought the nation back together, but somehow we still know the Confederate battle flag better than the truce flag,” she told artnet News. “There’s an argument to be made that we’re still embattled as a nation. We still haven’t come to terms with racial justice and equality, with the fact that for all our spouting of democracy, we’re still a nation built on the genocide of Native people and the subjugation of African people.”

Confederate Flag of Truce. Collection of the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

The historic object is utterly unassuming, a fringed white linen dishtowel yellowed with age, with three skinny red stripes along its border. And despite the important role it played in ending the bloodiest conflict in our nation’s history, hardly anyone knows it exists.

In comparison, the Confederate battle flag has been slapped on countless commercial goods—one of Clark’s pieces at the Fabric Workshop, Propaganda, offers a written list of 200 items decorated with the Stars and Bars that are available for purchase, including bikinis, bumper stickers, and yoga mats.

That the truce flag has been forgotten while the battle flag has been memorialized—defended as a symbol of Southern heritage, rather than denounced as one of a violent conflict fought in defense of slavery—seemed to Clark an historical imbalance that she could help correct.

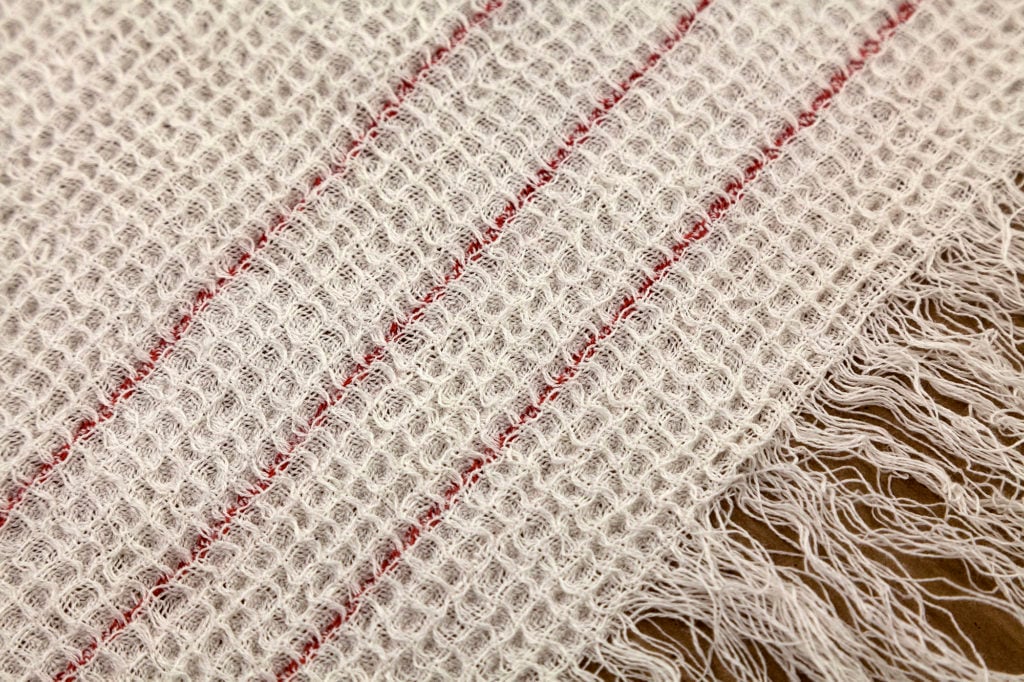

Sonya Clark, in collaboration with the Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, Woven replica of the Confederate Flag of Truce (2019). Photo by Carlos Avendaño.

“There are symbols that we associate with the Civil War: Lincoln’s top hat, certainly the Confederate battle flag… I don’t know what else. But why not the Confederate truce flag?” Clark asked. “Why not the flag that ended the war that almost brought our nation apart?”

To raise awareness of the Confederate truce flag, the artist has teamed up with Fabric Workshop team to create no fewer than 101 replicas of the humble cloth for “Sonya Clark: Monumental Cloth, the Flag We Should Know.” That includes a massive one, ten times the size of the original at 15 by 30 feet—a visual manifestation of its historic importance.

Sonya Clark, Unraveling, 2015. Photo courtesy Sonya Clark.

Through Clark has worked with the Confederate battle flag in past projects—her piece Unraveling saw her painstakingly reduce it to strands of red, white, and blue thread—there is only one battle flag on view at the Fabric Workshop. (The artist has a second Philadelphia show, which she describes as more of a retrospective, opening at the African American Museum in May.)

On Saturday night, Clark staged a performance called Reversal featuring a small washcloth decorated with the Confederate battle flag—a deliberate inversion of the truce flag’s dishtowel origins.

“I’m using it for its purpose, which is to clean things,” said Clark, who got down on her hands and knees to wash the museum floor. She removed a thick layer of dust collected from two of Philadelphia’s most historic sites: Independence Hall and the Declaration House. As she worked, the text of the Declaration of Independence slowly appeared, written on the floor.

Sonya Clark, in collaboration with the Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, Woven replica of the Confederate Flag of Truce (2019). Photo by Carlos Avendaño.

To make her truce flag, Clark used historically accurate madder root dye for the stripes and the same traditional waffle weave technique that would have been used to make the original. Visitors to the exhibition can try their hand at the process as well, on one of nine looms included in the show.

“The idea is that it’s kind of a reenactment,” Clark joked, noting that fittingly, the Fabric Workshop is located in a former flag factory. “There’s this lovely serendipity in that.”

Samples of linen dyed with madder root to recreate the stripes on the Flag of Truce. Photo by Carlos Avendaño.

Weaving experts will be on hand to teach museum-goers the ropes, and each flag produced will feature the imperfections and errors of first-time weavers. By the exhibition’s end, Clark expects them be much longer than the original flag, added to continuously throughout the show’s run.

This hands-on element is both generative and educational, highlighting how little the average American knows about textile production.

Sonya Clark, in collaboration with the Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, Woven replica of the Confederate Flag of Truce (2019). Photo by Carlos Avendaño.

“We’re surrounded by cloth all the time, and yet we don’t even understand the structure of it,” Clark said. In asking visitors to help recreate the truce flag, she’s hoping to underscore not just what we take for granted about the clothes that we wear, but what we take for granted about our nation’s history.

Seated at the loom, visitors can feel the linen thread and sense the absorbency of the weave, reminding themselves that the dishtowel that became the truce flag was made to clean up messes. In one way, it’s fitting—what bigger mess could there be than the Civil War? In another, however, it is wholly inadequate. Only a much deeper reckoning can blot out this stain.

“Sonya Clark: Monumental Cloth, the Flag We Should Know” is on view at the Fabric Workshop and Museum, 1214 Arch Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, March 29, 2019–August 4, 2019.

“Sonya Clark: Self-Evident” is on view at the African American Museum, 701 Arch Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, May 18–September 8, 2019.