Law & Politics

A Legal Battle Between Sotheby’s and a Dealer Over a Record-Setting Keith Haring Painting Is Headed for Trial

The winning bid set a record for the artist, but the house says the bidder never paid up.

The winning bid set a record for the artist, but the house says the bidder never paid up.

Brian Boucher

A legal fight between Sotheby’s and a dealer over a Keith Haring painting will get its day in court. On Thursday, a New York Supreme Court judge dismissed the auction house’s request for a summary judgment against Anatole Shagalov, who the house claims ponied up a record-breaking bid for the work but then failed to pay up. The decision clears the way for a trial.

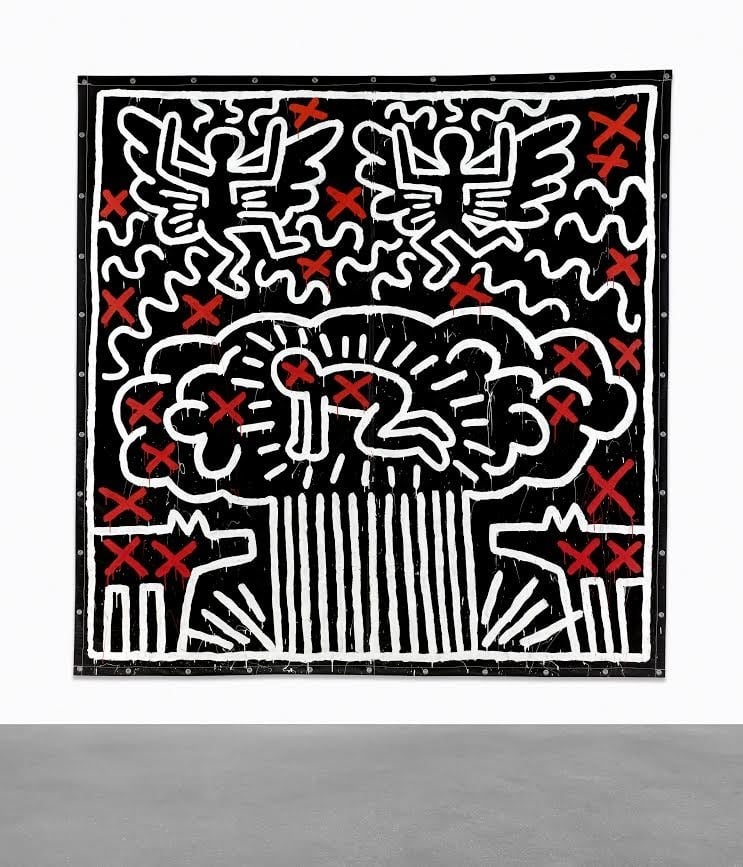

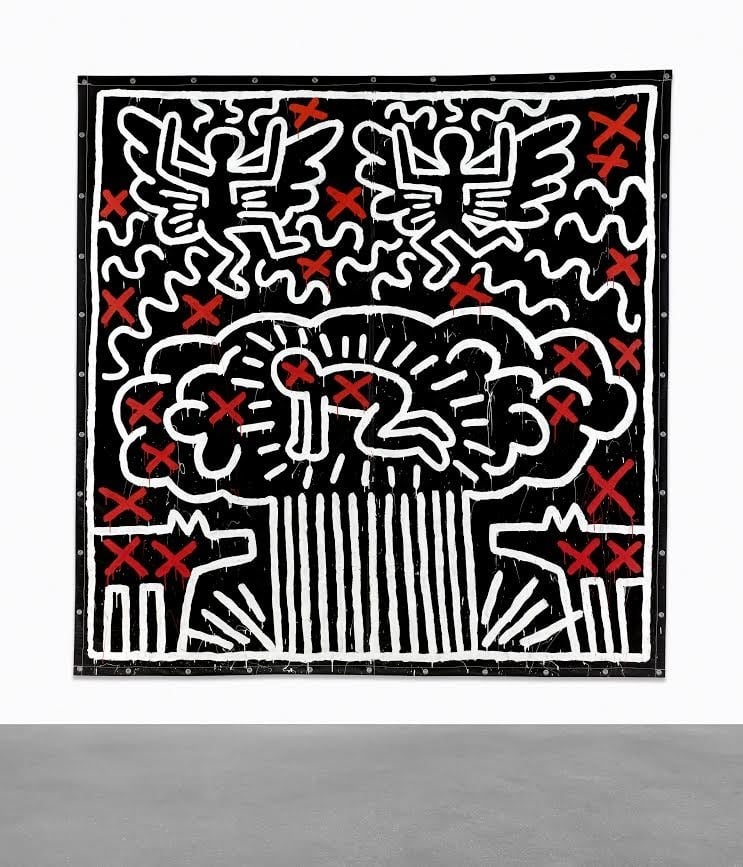

Shagalov, based in Great Neck, New York, was the winning bidder on a 10-foot-square Keith Haring painting on a plastic tarp that was offered at Sotheby’s major Modern and contemporary art sale in May 2017. The price, with fees, was $6.5 million dollars—an auction record for the artist—on a presale estimate of $4 million–$6 million.

Things began to unravel soon after the sale, and Sotheby’s filed suit against Shagalov and his company, Nature Morte, in August 2017, to recover the purchase price. Shagalov, however, claims that the house had orally agreed to give him time to pay. Sotheby’s disputes this: The house’s lawyer, John Cahill, says that such agreements would always be made in writing and that no such written agreement exists. (Emails filed as exhibits in the case indicate that Sotheby’s chief operating officer, Adam Chinn, “shouted ‘NO!!!'” when asked whether Shagalov had been orally granted any special terms.)

When Sotheby’s hadn’t received payment five months later, it sold the painting to another client for $4.4 million, and it is holding Shagalov accountable for the remaining $2.1 million.

Anatole Shagalov. © Patrick McMullan. Photo Max Rapp.

Mathew Hoffmann, Shagalov’s lawyer, maintains that the dealer was on the hunt for another buyer. According to a court transcript quoted by Bloomberg, Hoffman says his client’s modus operandi is “always the same, which is borrow money, buy art, sell art, pay loans back.”

Shagalov argues that Sotheby’s didn’t provide sufficient notice that it would sell the painting to another party. The dealer claims that he had secured a buyer in Marco Mercanti, the founder of Oblyon, a Madrid-based art advisory. Mercanti was willing to pay $5 million, says Hoffmann, which would have halved the amount he owed Sotheby’s. (Mercanti’s website indicates that he previously worked in the legal and compliance departments of Sotheby’s London before establishing the art law department at Crowe Horwath International.)

Shagalov contends that the house didn’t sell the work in a “commercially reasonable manner” and should have tried harder to get a higher price than the $4.4 million for which it sold the painting in 2016. Cahill rejects that claim—a sale price within the original estimate is reasonable, he says.

To make the case even knottier, Hoffmann told artnet News that the question over installments is minor compared to the information Sotheby’s is keeping confidential. Because some of the information in the case is reserved for attorney’s eyes only, he can’t make his full case public.

“If Sotheby’s case is so strong,” he said, “why not produce what they have to produce, and show all the facts, and let’s see if they can prove their case? We don’t think that they will be able to.” Cahill, Sotheby’s lawyer, says that only the identities of the underbidders have been redacted to preserve their privacy.

Meanwhile, Sotheby’s isn’t the only auction house chasing Shagalov. Phillips sued the dealer in July 2016, claiming that he failed to pay $6 million for winning bids on works by Morris Louis and Christopher Wool.