People

David Goldblatt, Photographer of South African Apartheid’s Brutality, Dies at 87

"I’m interested in the conditions that give rise to events," Goldblatt once said.

"I’m interested in the conditions that give rise to events," Goldblatt once said.

Eileen Kinsella

David Goldblatt, the South African photographer who rose to fame for his unflinching photographs of life both during and after apartheid, has died at age 87. He was asleep at his home in Johannesburg when he died early this morning, according to a statement from Goodman Gallery, which represented the artist for many years and will now represent his estate.

“David Goldblatt’s death is a very sad day for us all at Goodman Gallery and indeed for South Africa,” said director Liza Essers in a statement. “David was a dear friend and I will miss him very much. I am privileged to have known him and worked closely together for the past decade. In that time, David offered me his unwavering support, commitment and mentorship. David’s passing is a significant loss to South Africa and the global art world.”

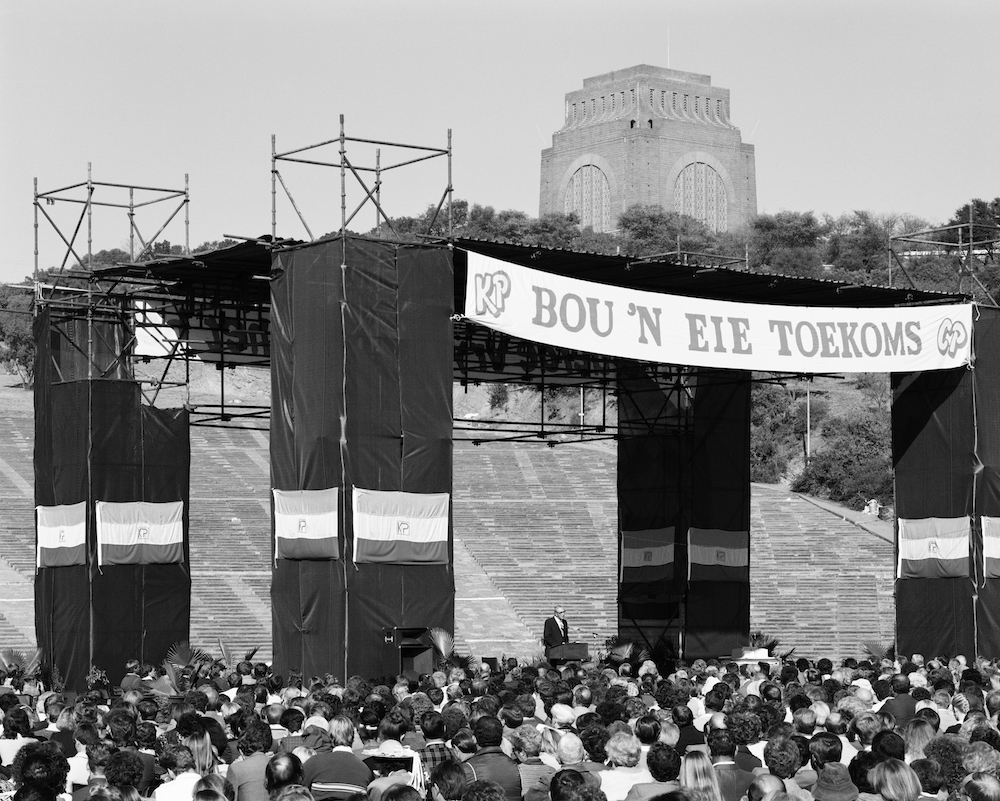

David Goldblatt, The Voortrekker Monument and a Sunday service of the ultra-conservative Afrikaanse Protestantse Kerk (Afrikaans Protestant Church) after a rally of right-wing Afrikaners who threatened war if South Africa became a non-racial democracy, Pretoria, Transvaal, 27 May 1990 (1990).

Goldblatt was born in 1930 in Randfontein in Johannesburg. At the age of 18, he began photographing the structures, signs, people, and landscapes around him. Though the scenes often look somewhat ordinary on first glance, they frequently reflect the specifics of the brutality and injustice imposed on the country’s black population under apartheid.

Goldblatt said that during those years his prime concern was with values. “What did we value in South Africa, how did we get to those values and how did we express those values,” he once said, according to Goodman Gallery. “I was very interested in the events that were taking place in the country as a citizen but, as a photographer, I’m not particularly interested, and I wasn’t then, in photographing the moment that something happens. I’m interested in the conditions that give rise to events.”

I was fortunate enough to meet Goldblatt during a trip to South Africa last year. On a visit to his Johannesburg home, he spoke about how the rules imposed on blacks—such as the mandate to carry an identification card at all times—were thinly veiled excuses to detain and arrest them.

Over the course of his illustrious career, Goldblatt’s photographs were published in newspapers and exhibited in museums all over the world. Earlier this year, the Pompidou Center in Paris held a lauded retrospective of his work. His photos will also be the subject of another show at MCA Sydney this October.

David Goldblatt, Ozzie Docrat with his daughter Nassima in his shop before its destruction under the Group Areas Act, Fietas, Johannesburg (1977).

In 1998, Goldblatt was the first South African artist to have a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In 2001, a retrospective of his work, “David Goldblatt: Fifty-One Years” began a tour of galleries and museums including those in Lisbon, Oxford, Munich, Brussels, and Johannesburg. He was one of the few South African artists to exhibit at documenta (in 2002) and again in 2007. He has had solo exhibitions at the Jewish Museum and the New Museum in New York. His work was also included in the exhibition “ILLUMInations” at the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011.

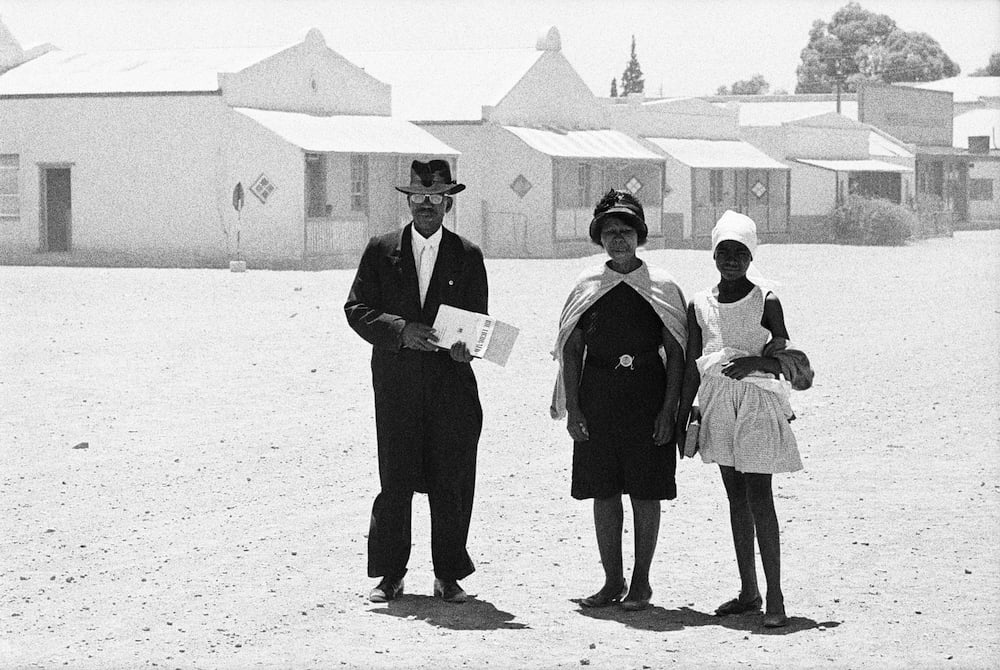

David Goldblatt, An elder of the Dutch Reformed Church walking home with his family after the Sunday service, Carnavon, Cape Province (Northern Cape) (1968).

Earlier this year, Goodman announced that Goldblatt had reached an agreement with Yale, which transferred his entire archive of negatives to the university. A digital archive of Goldblatt’s work will be created in South Africa and made available to the public for free through an initiative known as the Photographic Legacy Project.