Art World

The 1918 Spanish Flu Wreaked Havoc on Nearly Every Country on Earth. So Why Didn’t More Artists Respond to It in Their Work?

There are few obvious depictions of the disease, despite its devastating worldwide toll.

There are few obvious depictions of the disease, despite its devastating worldwide toll.

Taylor Dafoe

More than a century after it killed upwards of 17 million people around the world, the 1918 flu pandemic, also known as the Spanish flu, has come charging back into the public consciousness. The disease—the most devastating of its kind in modern history—bears some eerie similarities to COVID-19, especially in its person-to-person transmission and global impact.

Yet in the annals of cultural history, the flu of 1918 is little more than a historical footnote. There are few obvious depictions of the disease in canonized art and literature, and the images it recalls are not as vivid as those that followed, say, the AIDS crisis.

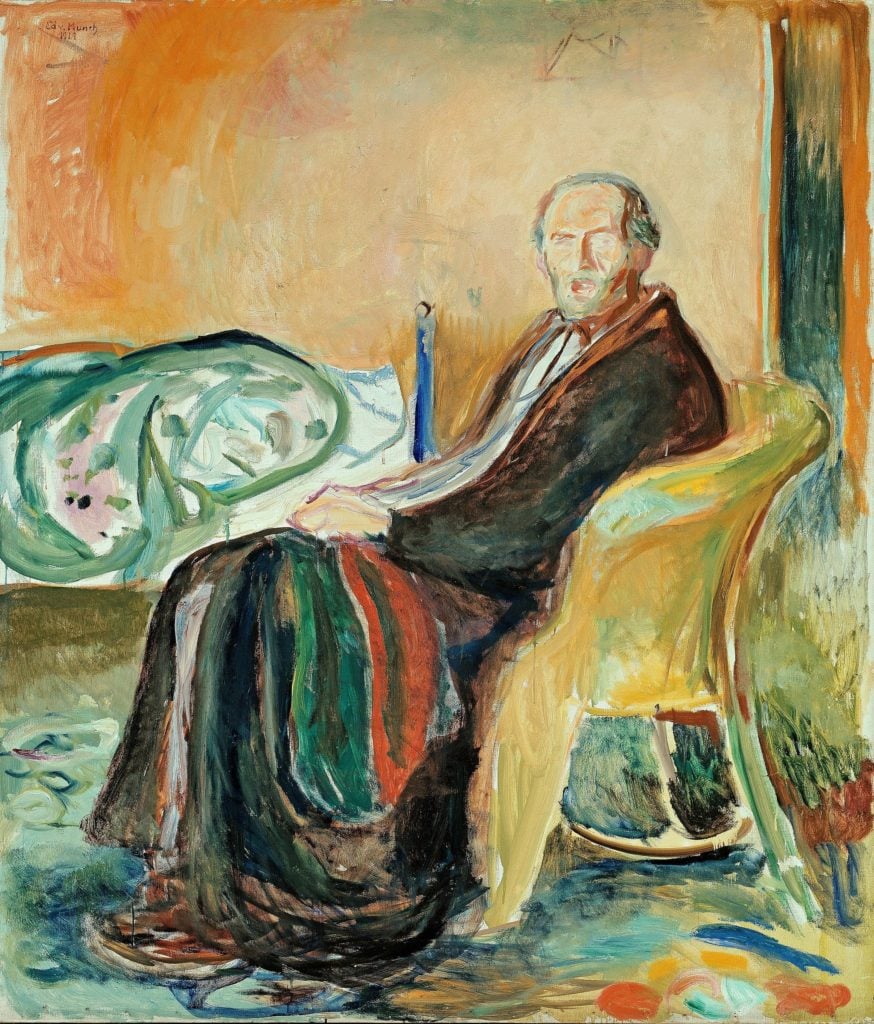

Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas,” probably early 1918. New Contributed Photographs Collection, Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine.

“If you close your eyes, the iconography doesn’t immediately flood over you in the way that it does with war or other historical events,” says curator Trevor Smith, a curator at the Peabody Essex Museum and the co-curator of an exhibition on the Spanish Flu held last year at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia.

“Millions of people lost their lives around the world, and it’s hard to even wrap your head around that,” he says. “There haven’t been many monuments or memorials to the people who died in that pandemic.”

Though it was conceived as something of a specialized exhibition at a niche medical history museum, his show, “Spit Spreads Death,” has gained newfound resonance as people look to draw lessons from the Spanish flu.

Egon Schiele, The Family (1918).

So why was the Spanish flu so long forgotten?

The most commonly cited reason is World War I. The flu took hold in January of 1918, about 10 months before the war ended. And though the highest estimates for the number of dead from the disease (around 50 million) outnumber the high estimates for how many were killed in the war (around 40 million), the far-reaching political and social implications of the global conflict have taken precedence in the macro-history of the 20th century.

Artists, too, were more drawn to depictions of the war. Marsden Hartley’s Portrait of a German Officer (1914); John Singer Sargent’s Gassed (1918–19); and portfolios by Otto Dix (The War, from 1924) and Kathe Kollwitz (Krieg, from 1921–22) speak to an almost universal fascination with the cataclysmic impact of the war.

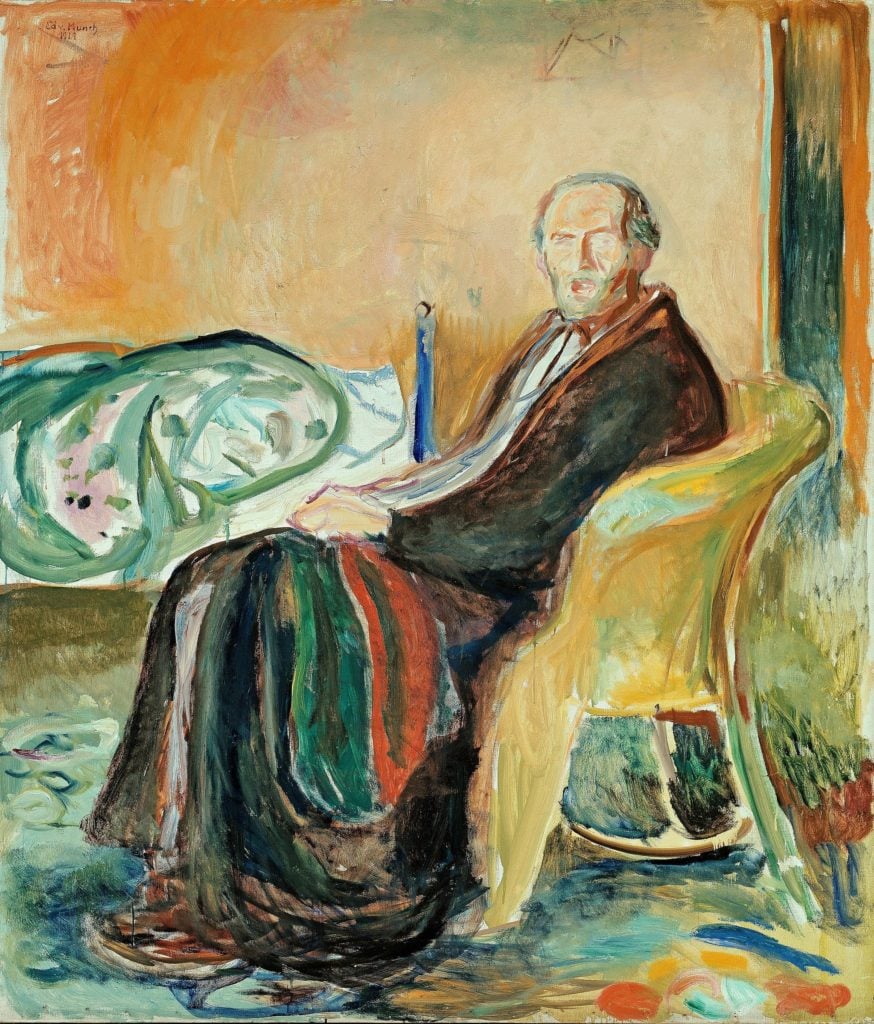

But when it comes to the Spanish flu, there are only a few notable artworks recording its existence. Edvard Munch, one of the most recognizable names to have been infected, was fascinated by the disease because it drew out his long-term fascination with terminal illnes. He made two noteworthy depictions of the flu’s effects: the disquieting Self-Portrait With the Spanish Flu (1919) and the more macabre Self-Portrait After the Spanish Flu (1919–20).

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait After the Spanish Flu (1919).

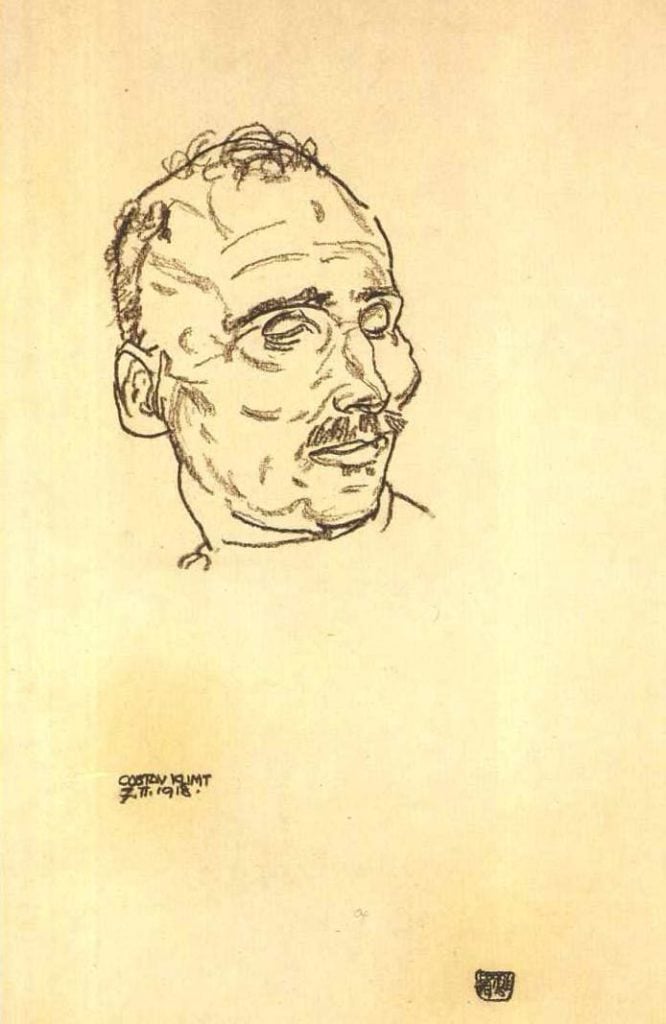

Then there’s Egon Schiele’s 1918 painting, The Family, which depicts the artist, his wife, and a baby. It was never finished: Schiele and his spouse died from the flu before he could complete the work.

“Schiele was at the peak of his career in 1918,” says Jane Kallir, director of the Galerie St. Etienne and the author of Schiele’s catalogue raisonné. “He had his first really successful exhibition in March of that year, his wife was pregnant with their first child, and he had rented a big studio in the summer. He was doing well. Then he was just gone.” (Indeed, the disease often killed patients very quickly, sometimes just three days after they began exhibiting symptoms.)

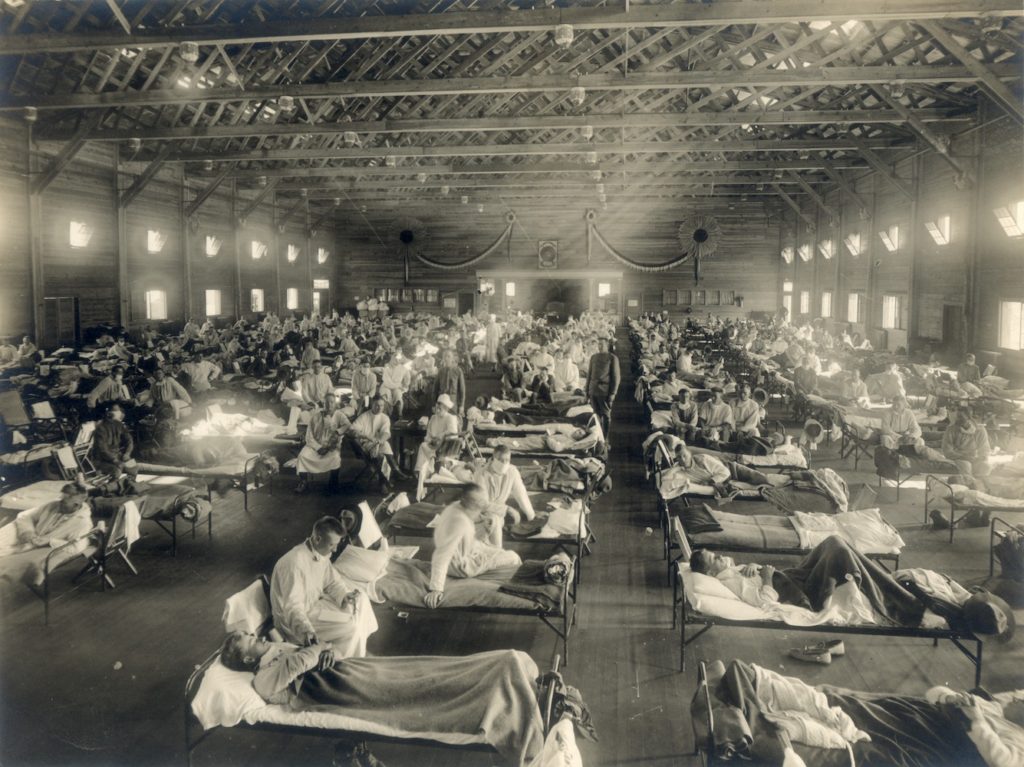

So while the list of canonized artworks is small, so too is the list of notable deaths. Besides Schiele, one of the only other notable artists to die in the pandemic was the American Precisionist Morton Schamberg. Guillaume Apollinaire, the French poet, art critic, and champion of Cubism also died from the disease, and Gustav Klimt was another possible victim: he suffered a stroke and contracted pneumonia prior to the full onset of the flu, and died in February 1918.

Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt on his death bed (1918).

“He was 56, his habit was to have a bowl of whipped cream for breakfast every day, and he was seriously overweight,” Kallir says wryly of Klimt. “So there were underlying conditions there.”

There’s a reason the Spanish flu did not kill many prominent artists, and it has to do with one of the key distinctions between it and COVID-19.

“The 1918 pandemic, as opposed to the coronavirus today, was that it was a disease of youth,” Kallir says, noting that people between their late teens and mid-30s were those most susceptible. “A lot of people who were lost to that disease died before they ever had a chance to achieve anything.”

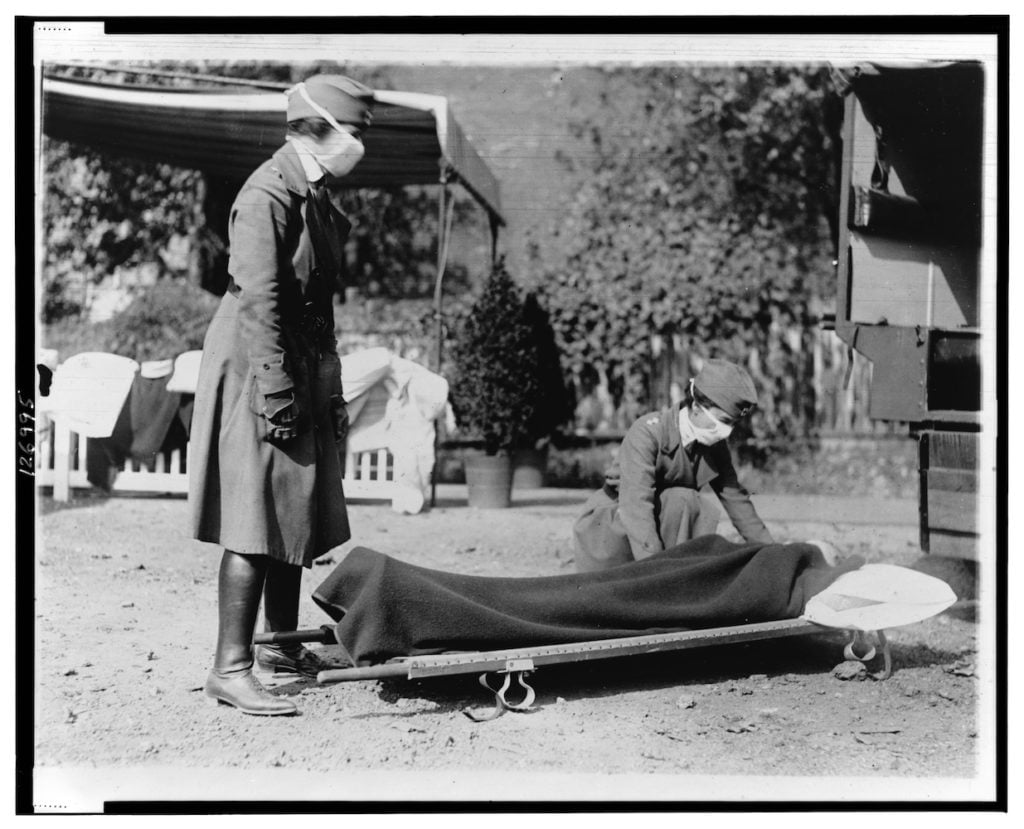

A demonstration at the Red Cross Emergency Ambulance Station in Washington, D.C., during the influenza pandemic of 1918. Courtesy of the National Photo Company Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

For “Spit Spreads Death,” Smith and his team commissioned a collective called Blast Theory to conceive of a new work to commemorate the Spanish flu.

Their solution was to organize a 500-person parade, which took place on Broad Street in Philadelphia last September. Marchers held up signs with the names of victims and healthcare workers who died during the pandemic in reference to a parade of 200,000 people that took place in the city in 1918, which greatly exacerbated the number of cases in the city and led to an untold number of deaths.

When the performance took place, Smith says he reflected on “just how lucky we were to not be facing that crisis.” Now the situation is quite different.

But Smith—who happened to travel to Wuhan last December (though he did not contract the coronavirus)—says he is unsure how new art will reflect the current pandemic.

“Every period has produced works of art that have moved us in different ways, and I have no reason to think that this period will be any different,” he says. “I just think it’s too early to zero in on them.”

A parade honoring the victims of the Spanish Flu in Philadelphia, September 2019. © Blast Theory. Photo: Tivern Turnbull.

Kallir says much the same, noting that there are far more questions than answers right now.

She does, however, offer one bold perspective.

“I am not sure this is going to accelerate the dominance of the mega-galleries and the mega-artists and the mega-wealthy,” she says. “Are we going to have an appetite for a big silver Jeff Koons bunny after this?”