Art & Exhibitions

A New Show Charts Germany’s Love Affair With Van Gogh—and Seeks to Solve the Mystery of Where One of His Most Famous Works Is Hidden

The Städel Museum's “Making Van Gogh" contains many highlights, and a mysterious empty frame.

The Städel Museum's “Making Van Gogh" contains many highlights, and a mysterious empty frame.

Quynh Tran

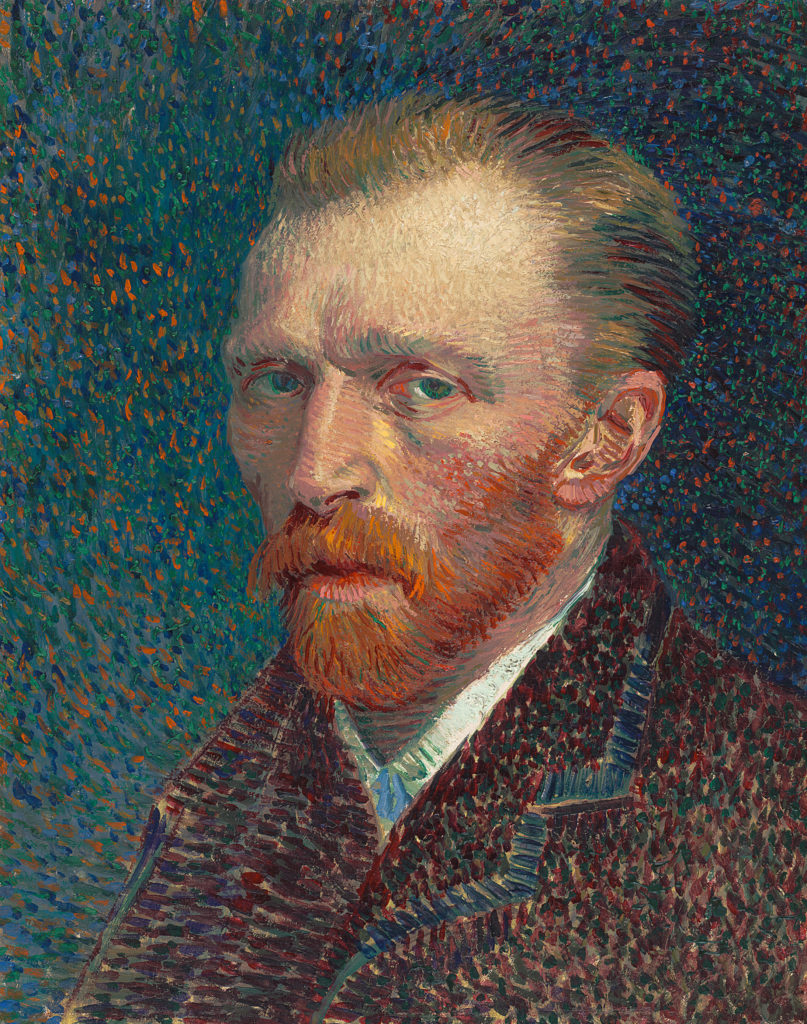

The story of the tormented artist who shot himself in the very same cornfields that he painted so memorably was too good not be told. By the time the German art critic and novelist Julius Meier-Graefe cemented the legend of the tragic genius in his bestselling (and largely fictitious) biography about Vincent van Gogh in 1918, the dead Dutch painter was already considered one of the most influential figures in Modern art.

“Making Van Gogh. A German Love Story” at Frankfurt’s Städel Museum explores the marketing and mythologization of van Gogh at the hands of the German art world—namely through critics such as Meier-Graefe, as well as the slew of German collectors, artists, and dealers who venerated him. As early as 1914, there were 150 van Gogh works in collections in Germany. The vast exhibition at Städel accentuates the critical role played by these agents of van Gogh’s posthumous success, at times with surprising details.

After five years of planning, the German museum has united 50 key works by van Gogh from around the world, bolstered by 70 works by the German artists he influenced, among them Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Paula Modersohn-Becker. Occupying the 32,000-square-feet underground extension of the institution, which normally houses its postwar and contemporary art collections, the show has a rather austere setting that puts the spotlight squarely on the intensity of van Gogh’s paintings.

“Vincent van Gogh is the godfather of German modernism,” said Städel’s director Philipp Demandt at the press opening last week, adding that the exhibition, which is on view until February 16, 2020, is probably the most elaborate in the museum’s history.

Photo: Städel Museum – Norbert Miguletz.

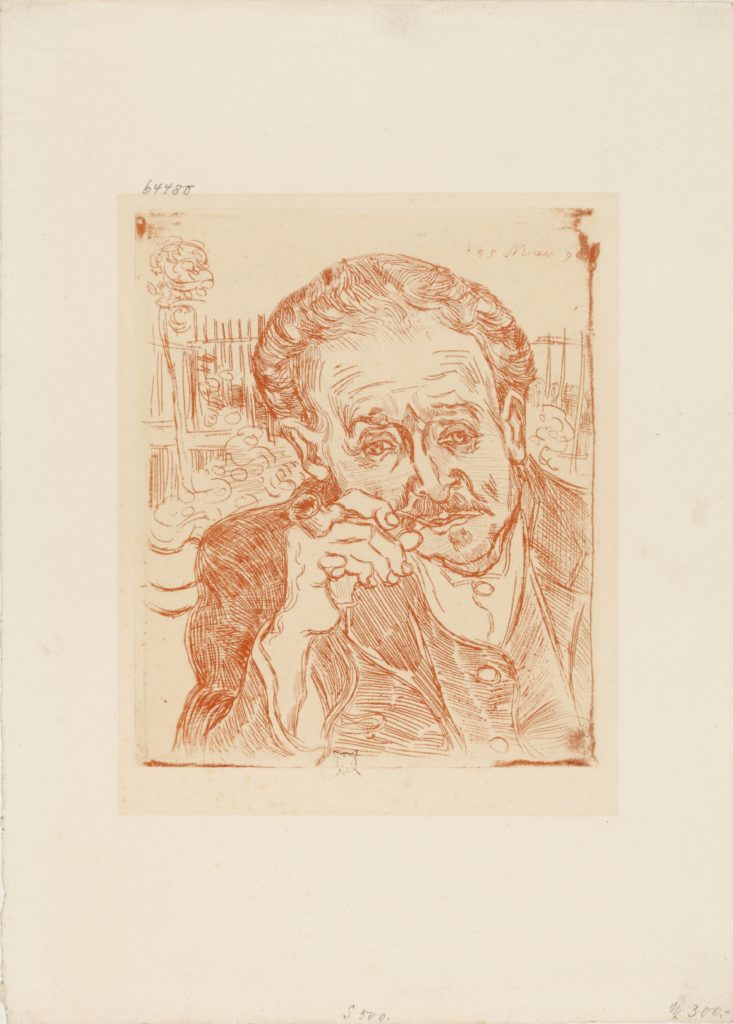

In fact, the Städel was one of the first public museums to purchase works by van Gogh ever and was, at one time, the proud owner of Portrait of Dr. Gachet, one of the artist’s most famous portraits. The melancholic painting depicts the neurologist and friend who treated van Gogh in his final months, an enigmatic work made just weeks before the artist committed suicide in 1890.

Acquired by the Städel in 1911, the so-called Dr. Gachet was one of the most treasured acquisitions of the museum. It hung on display in its permanent collection right up until the Nazis came to power. In 1937, the party confiscated the work under its rubric of “degenerate art,” a cultural policy that saw the seizure, sell-off, and destruction of many masterpieces. In anticipation of the current show, the institution undertook detective and journalistic efforts to find the “lost painting,” which has not been seen by the public in nearly 30 years. The original frame now hangs in the museum, but the canvas is still missing.

“In the course of our research, we found out where the painting is a few months ago. We tried to reach out to the owner but didn’t get any reply,” Städel’s Alexander Eiling, who curated the show with Felix Krämer of Düsseldorf’s Kunstpalast, told artnet News. After being seized by the Nazis (the museum tried, in vain, to protect it by putting it in a hidden room a few years before it was taken), the work was sold on the international art market at the behest of Herrmann Göring and, ironically, ended up in the collection of German Jewish émigré Siegfried Kamarsky under unknown circumstances.

Decades later, in 1990, Dr. Gachet was auctioned off at Christie’s by Kamarsky’s heirs for $82.5 million ($158.2 million in today’s value), in what was the most expensive sale of a work of art at the time. Since then, the portrait not been seen. The Städel was hopeful that, given their unique connection to the work, it might secure the loan. In the lead-up to the show, the museum commissioned a journalist to research and track the work’s winding history and its current location in a podcast.

Vincent van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Gachet (1890). Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main. Photo: Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Despite its absence, the image of the work remains omnipresent within the museum’s gallery: An etching of Dr. Gachet by van Gogh is on display, mirrored by Paul Gachet’s own etching of van Gogh, which he made of his artist-patient while he was on his deathbed.

The empty golden frame from 1911 is a stark reminder of the losses incurred during wartime. It has also become a selfie magnet for visitors. (Van Gogh, incidentally, reportedly preferred a frame of simple white wood.)

But van Gogh’s posthumous “love story” with Germany does not begin or end with Dr. Gachet. His most important gallery, run by the Jewish editor and dealer Paul Cassirer, was based in Berlin. Cassirer had included five of van Gogh’s works in the 1901 Berlin Secession exhibition. In 1906, the artist’s comprehensive correspondence with his brother Theo van Gogh was first published in Germany, and by the outbreak of World War I, just 24 years after his suicide, some 120 paintings and 36 drawing of his works were peppered throughout German collections.

Some of these works, and the stories of early champions of the artist, form the most fascinating components of the Städel show. There is the 1888 Portrait of Armand Roulin, the first painting to be bought by a German museum, the Museum Folkwang in Essen, in 1903. The first acquisitions by the Städel are also included, like Farmhouse in Nuenen and the drawing Peasant Woman Planting Potatoes, both from 1885.

Vincent van Gogh’s Haystacks (1888). © Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest.

There is also the empty landscape of Wheatfield with Cornflowers from 1890, a work that depicts the fields outside of Auvers-sur-Oise where the artist ended up killing himself that same year. The painting was owned by Jewish artist Max Liebermann starting in 1907, who passed it on to his daughter Käthe just before the breakout of World War II. It is now in the collection of the Fondation Beyeler in Switzerland.

Demandt acknowledges the importance Germany played in salvaging the artist from relative obscurity: “It was especially gallery owners, artists, collectors, and museum directors in Germany, many of them of Jewish origin, who became interested in Van Gogh’s painting and ultimately defended it against nationalist tendencies and political instrumentalization.”

“Making Van Gogh: A German Love Story” runs October 23 to February 16, 2020 at Städel Museum in Frankfurt am Main.