Staff complaints about leadership at the Detroit Institute of Arts—one of the largest museums in the United States—are mounting, including charges of ethics violations and nepotism.

Six current and former employees who spoke to Artnet News on the condition of anonymity allege that the museum’s director, Salvador Salort-Pons, has misused the museum’s resources to grant favors to friends and family, conducted inequitable hiring practices, and lacks sufficient knowledge of race and diversity issues.

The accusations come at a time when museums across the country are experiencing turmoil from within as staff members launch open letters, rogue Instagram accounts, and petitions to demand leadership changes, better staff treatment, and a stronger commitment to equity and diversity. For his part, Salort-Pons says the employees’ characterizations are not accurate and that he has behaved properly during his 12 years at the museum, including the five years he has served as director.

The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, Michigan, USA. Courtesy Wikicommons.

A Pattern of Nepotism

Among the more serious allegations against Salort-Pons is that he abused his authority to bolster personal relationships and the value of his family’s art collection.

The museum has exhibited two paintings owned by Alan May, Salort-Pons’s father-in-law—El Greco’s St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata and a painting attributed to the circle of Nicolas Poussin, An Allegory of Autumn—leading a whistleblower to file a conflict-of-interest complaint with the IRS and the Michigan attorney general. (Showing a work at a prestigious museum can enhance its market value.)

The chair of the museum’s board, Eugene Gargaro, told the New York Times that Salort-Pons had disclosed the details of the loan and the board approved it. Graham Beal, who was the museum’s director at the time of the Poussin loan in 2010, told the paper, “The loan(s) from Alan May was/were totally above board and benefited the DIA as much, if not more, than the lender.”

In comments to Artnet News, Salort-Pons said that while the loans did not violate any existing museum policies, the DIA will hire an independent law firm to conduct a review of the museum’s loan policies and procedures. (The institute’s guidelines, cited by the Times, say that loans from staff members’ family collections can be beneficial but “care should be used to achieve objectivity in such cases.”)

Still, some say the questionable ethics don’t stop there. The director also used the museum’s conservation department to clean and restore paintings owned by May, including those that were not intended for view at the museum.

“We knew there were paintings coming through the conservation department that were not the museum’s paintings. You’d see that there was a painting purchased at auction and sent to the museum. They would have his name [Alan May] on there,” said one former employee. “I saw them on multiple occasions.”

Gargaro did not respond to a request for comment about whether this would qualify as an ethics violation.

Salort-Pons said the museum is reimbursed for work done on museum time for private collectors. “For works on loan, conservation work is typically done pro bono by the DIA,” he added. “The museum provides conservation services to the entire region.”

Inequitable Hiring Practices

Critics point to the museum’s turnover rate in recent years as emblematic of broader unrest. Since Salort-Pons was promoted to director, in 2015, 62 of the institution’s 371 employees have left, according to a list compiled by staff, many of them having held high-ranking positions, including a chief operating officer, five vice presidents, two executive directors, and four curatorial department heads.

Salort-Pons told Artnet News via a representative that these numbers were “not accurate.” While he did not provide different numbers, he said that the museum’s annual turnover rate in 2019 was 9.6 percent, which is below the national average of 27 percent.

Sources also alleged that, in multiple instances, Salort-Pons unilaterally filled job openings without posting them publicly or opening them up to a competitive pool of candidates, which could have attracted more qualified and diverse hires. “There’s a faux pretense that searches are equitable,” said one former staffer.

In 2016, Salort-Pons named Felicia Eisenberg Molnar, a friend of his wife’s and a public-relations veteran, as the museum’s new executive director of strategic initiatives. Staffers who were there at the time say they were surprised that such a senior position was filled without a public-facing search process, and that it went to someone who they characterized as lacking relevant qualifications.

“That sent ripples through the museum,” said one former employee. “People were very upset.”

Salort-Pons responded that DIA has always adhered to its hiring policies, which permit the director to single-handedly decide hires at the executive director level and above without posting the position.

Still, sources say that whether or not his hiring habits were by the book, they nonetheless left staff feeling like diversity wasn’t a priority and that, as potential internal candidates, they too were being passed over for jobs for which they were qualified.

“There were no growth opportunities for me at the DIA and, at the same time, this was a director who was creating positions for other people without a competitive posting or interview process,” added the former employee.

Unanswered Grievances

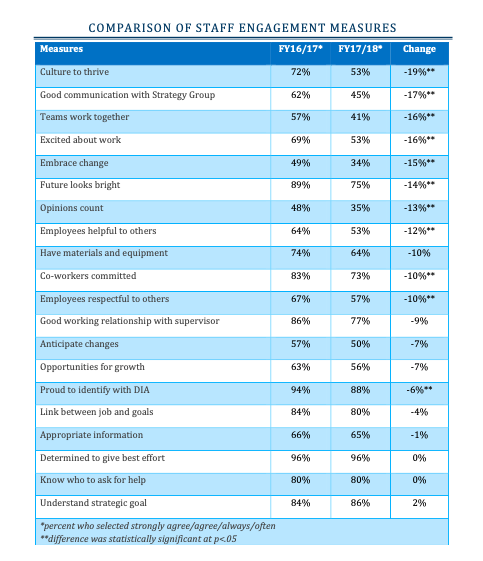

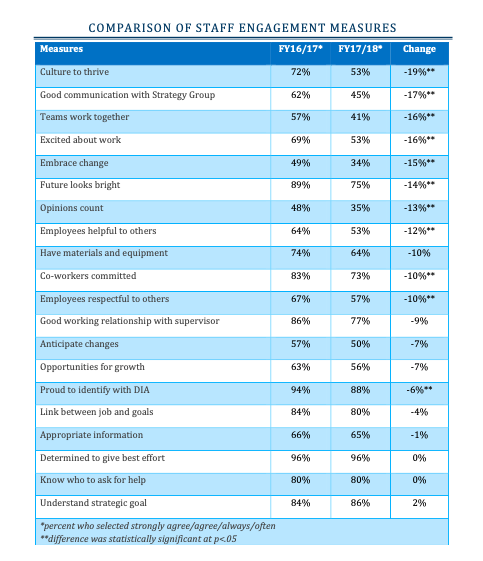

In 2017, a staff survey revealed markedly low morale among workers. In 17 of the 20 categories that aimed to measure the quality of internal culture, the motivation of employees, and the clarity of internal communication, ratings sank from the previous year. Nearly half of employees disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement “the DIA provides a culture in which I can thrive.”

Detroit Institute of Arts 2017 employee engagement survey.

As a result, the museum convened an all-staff gathering in its great hall. Staffers present at the 2017 event who spoke with Artnet News said they felt that, rather than management engaging with their concerns, they were lectured by “talking heads.”

“I remember somebody asked Salvador to elaborate on his idea about how the museum should be like a town hall and he rolled his eyes,” one former employee said. “I think we’re at a moment where institutions have to do some housecleaning and people can tell when there’s sincerity behind an institution really wanting to lean toward change and these other moments where people just continually speak to you, and people know the difference.”

A senior employee who had spent two decades at the museum told Artnet News that the all-staff meeting “was the last straw” and resigned soon thereafter.

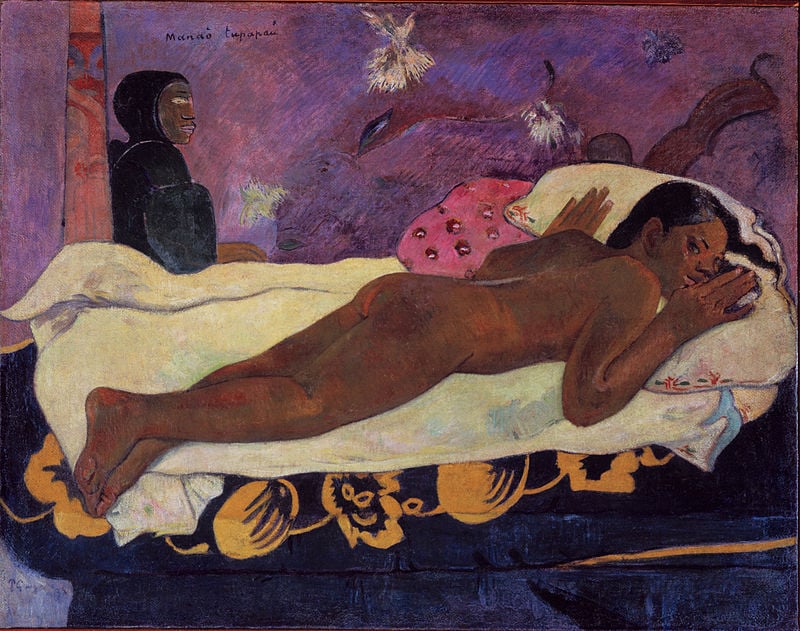

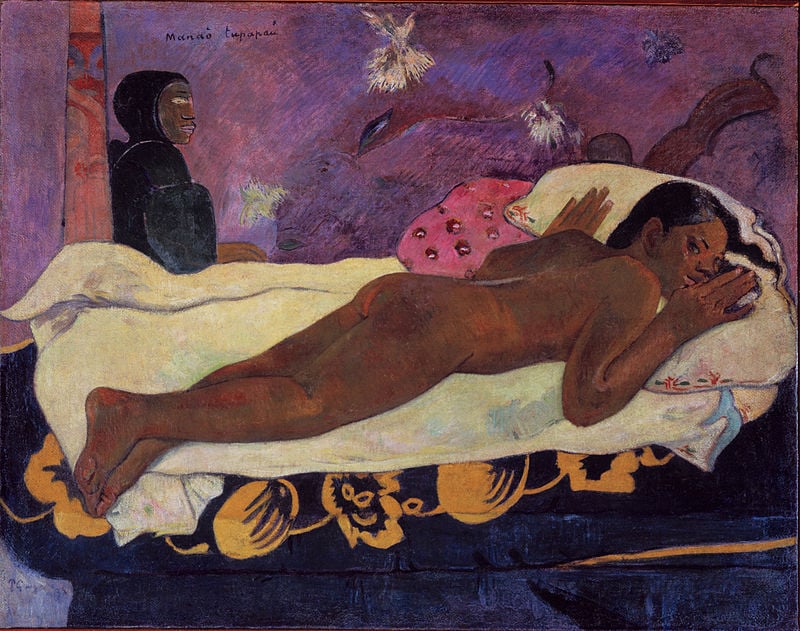

Paul Gauguin, Spirit of the Dead Watching (1892).

Another staffer, Andrea Montiel de Shuman, a former digital experiences designer at the museum, resigned last month after she says the museum failed to address her concerns about its response to the Black Lives Matter movement and its decision to display Gauguin’s painting of his 13-year-old Tahitian “wife” without a mention of sexual assault.

“The only way I see my beloved institution restoring the quality of work our constituents deserve is if it has the courage to look in the mirror and meaningfully reflect, then commit to not only apply, but to actively endorse the development of visitor-centered, education and evaluation practices that lead to the eradication of racist structures,” Montiel de Shuman wrote in a Medium post about her resignation.

Her comments were echoed by several former employees, who said that the museum’s human resources department failed to address serious grievances brought by staff. (“The DIA has non-discrimination, harassment and anti-retaliation policies and it takes pride in being an EEO employer,” Salort-Pons said.)

A Question of Equity

The Detroit Institute of Arts has a unique relationship to its community. In 2012, voters in three surrounding counties took the unusual step of approving a dedicated property tax to help shore up the museum’s finances. In March, voters agreed to renew the program, which Salort-Pons has cited as a strong sign of public support for the institution.

But many sources who spoke to Artnet News said that the museum’s community outreach is also affected by the fact that Salort-Pons, who is originally from Spain, is “naive” about the complexity of issues surrounding race, inclusivity, and representation in the US. (Detroit has the largest Black population of any city in the country, at 82.7 percent, although the surrounding counties behind the millage are predominantly white. A high proportion of the DIA’s visitors—77 percent—come from the Detroit tri-county area, rather than as tourists.)

Staff say Salort-Pons’s approach has caused diminished confidence in his leadership, particularly among non-white employees. The Times reported that Salort-Pons “conceded that his European background meant that initially he had had a limited understanding of the Black struggle in America but was taking steps to improve diversity.”

Performers in front of the Detroit Industry murals by Diego Rivera at the Detroit Institute of Arts in 2012. Photo by Paul Warner/Getty Images.

Salort-Pons told Artnet News that he is “fully familiar with these issue and takes seriously my responsibilities as DIA director and coworker to see that gender, race, equity, and diversity issues are heard and addressed. That responsibility includes implementing diversity and community engagement initiatives as well as hiring qualified POC candidates.”

Sources say that when the museum does respond to staff concerns, it is usually by hiring an outside consultant. They say they undergo interviews and surveys but then see no resulting reports, changes in policies, or actionable plans.

“There was an all-staff email having to do with the political situation, race, equity, and inclusion,” said a former employee, who shared the email with Artnet News. “It said nothing and then, ‘we’re hiring a consultant.’ I almost spit out my drink. There’s no one on staff who can lead and solve any problems.”

Salort-Pons disagreed about the purpose of hiring the consultants. “Implemented actual change is not being done by any consultant, but rather by the DIA’s leadership involving all museum’s employees,” he said. “The DIA is committed to inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility in its workplace. As part of that commitment, among my immediate goals is hiring an executive to lead this work at the leadership level.”