Art World

How a Pipeline Is Threatening Native American Culture in North Dakota

This is a fight about whose culture matters.

This is a fight about whose culture matters.

Ben Davis

The current, generation-defining confrontation in North Dakota, led by members of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, is about challenging racism and defending the earth. It is also notably about cultural rights.

For those who have not been paying attention: The issue is the multi-billion-dollar, US Army Corps of Engineer-approved Dakota Access Pipeline Project, set to extend 1,172 miles across four states. In North Dakota, the pipeline was originally set to pass near the state capital, Bismarck, but was rerouted when it was deemed a potential threat to the water there.

Instead, it was set to pass just a half-mile north of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, with Dakota and Lakota leaders saying—logically—that it threatens their own water resources.

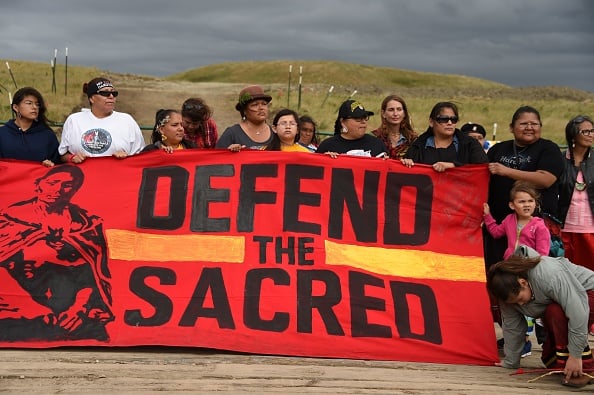

Opposition to the pipeline began in April, but has gathered historic momentum. As of this writing, the Sacred Stones protest camp is the most significant gathering of Native American tribal representatives in a century.

People gather at an encampment by the Missouri River, where hundreds of people have gathered to join the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s protest against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipe (DAPL), near Cannon Ball, North Dakota, on September 3, 2016. Photo Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty Images.

Supporters have responded to the call from as far away as Maine, Mississippi, and Hawaii. Indian Country has the story of Tlingit artist Doug Chilton, who trekked some 2,800 miles from Juneau, Alaska, to join the Sacred Stones encampment. The Broken Boxes podcast, normally devoted to contemporary indigenous art, has moving interviews from the camp:

A resolution of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in opposition to the pipeline expresses longstanding concerns about public health and welfare, and the environmental threat, but it also states that “the horizontal direction drilling in the construction of the pipeline would destroy valuable cultural resources.”

Such concerns were given greater force at the end of August when the tribe’s heritage expert, Tim Mentz, Sr., was allowed by an area rancher to survey land around the pipeline’s proposed route. On September 2, Mentz filed a declaration of his findings in United States District Court in Washington, DC, as part of the tribe’s attempt to halt construction under the National Historic Preservation Act.

In his survey, Mentz says, he discovered “82 stone features and archaeological sites, including 27 burial sites.” Some extended into the area of the pipeline (which he was not directly allowed to access), while others were near enough to it to be endangered by construction. Five, he found, were of particular note.

“Each of these sites,” he wrote, “carries great historic, religious, and cultural importance to the people of Standing Rock, other tribes of the Oceti Sakowin [Seven Fires Council], and me personally.”

Among those adjacent to the pipeline route were a stone representation of the Big Dipper constellation (“Iyokaptan Tanka”), signifying the burial site of a leader of the highest rank, which Mentz describes as “one of the most significant archaeological finds in North Dakota in many years.” An associated “Grave and Stone Arc,” directly in the path of the pipeline, represents the handle of the Dipper. A formation of stones marking an initiation site for the “Strong Heart Society” (“Chante Tinza Wapaha”), an elite group of warriors, stood to be damaged by any construction.

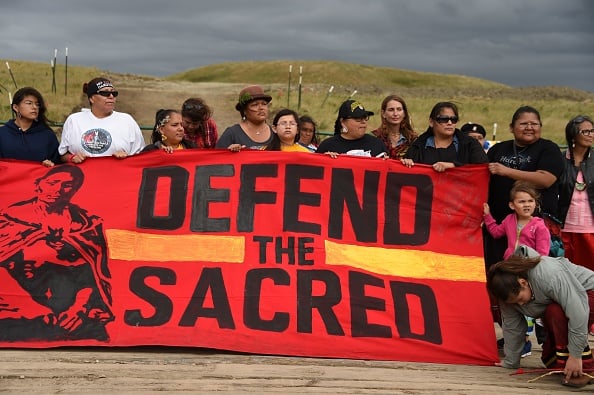

Members of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and their supporters opposed to the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) confront bulldozers working on the new oil pipeline in an effort to make them stop, September 3, 2016, near Cannon Ball, North Dakota. Photo Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty Images.

Immediately after the filing, early on Saturday morning—evidently ignoring both the weekend and the Labor Day holiday, and targeting the direct area referenced in Mentz’s filing—the company in charge of pipeline construction razed the terrain with bulldozers. Viral footage first aired on Democracy Now! shows protesters facing dogs and pepper spray at the site.

Jan Hasselman, a lawyer for the tribe, has said that she believes that Mertz’s findings were used as a “roadmap” for what to target. Daniel Estrin, general council and legal director of the Waterkeeper Alliance, wrote that “in the 23 years that I have practiced and taught environmental law, I have never seen such an outrageous, unconscionable, and bad faith abuse of the legal process.”

The company has responded to the charges by saying that it “is not destroying and has not destroyed any evidence or important historical sites.”

Filed on Sunday, Mentz’s follow-up declaration cataloging the results is as heartbreaking as a document written in the dispassionate language of legal testimony can be.

“Even without a formal damage assessment, my conclusion from what I have been able to see is that any site that was in the pipeline corridor has been destroyed,” Mentz writes. “Sites that are immediately adjacent the pipeline corridor are buried under berms of soil and vegetation that are as high as eight to ten feet. Anything under those berms is damaged if not destroyed.”

Given the high likelihood that Native gravesites were destroyed, he now asks that an injunction be granted to allow them to rebury their dead.

A court decision is expected today on whether the government will allow pipeline construction to go forward.

Standing Rock has become symbolic far, far beyond North Dakota. The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues has called on the US to respect tribal rights. Environmental groups have weighed in on the side of protesters (or “protectors” as they prefer to be called). Even celebrities like Leonardo DiCaprio, Divergent star Shailene Woodley, and future Aquaman Jason Momoa have added voices of support.

Anyone who cares about art and culture should add their own voices to the chorus. This is a fight about whose culture matters. It is a referendum on a society that would destroy its connection to the vital past in pursuit of a dying future.