People

Shattered Expectations: How a Feud With Ettore Sottsass’s Widow Led to the Cancellation of His Stedelijk Survey

Sottsass's widow and gallery argue that the museum never offered a cohesive exhibition plan.

Sottsass's widow and gallery argue that the museum never offered a cohesive exhibition plan.

Eileen Kinsella

In an unusually frank press release sent out last Friday, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam announced the cancellation of a much-anticipated spring show, the first Dutch retrospective of pioneering Italian designer Ettore Sottsass. After disagreeing about the exhibition’s concept, the museum said that Sottsass’s heirs and his estate’s gallery “no longer wish to collaborate” and withdrew their loans and permission to reprint a text.

“We were looking forward to working with the heirs to produce an exceptional, public-friendly exhibition,” said a statement from the museum’s interim director, Jan Willem Sieburgh, who stepped in after Beatrix Ruf’s abrupt departure last fall. But the museum locked horns with the artist’s widow, Barbara Radice, and Galerie Mourmans, Maastricht, which represents Sottsass’s estate.

“Months of discussion, however, proved fruitless. As a museum we cannot and will not allow the way in which we conceive our exhibitions to be dictated to us,” Sieburgh said. In the end, the museum was given “too little scope for interpretations we wished to explore in the presentation.”

In response, Barbara Radice and gallery owner Ernest Mourmans issued a joint statement, which took a jab at the recent controversy surrounding Ruf’s departure: “The development is symptomatic of recent events at the Stedelijk Museum, during which it became evident that both managerial and curatorial leadership have been amiss in recent years.”

They said they regretted the museum’s decision to cancel the show and called its statement to the press “misleading.”

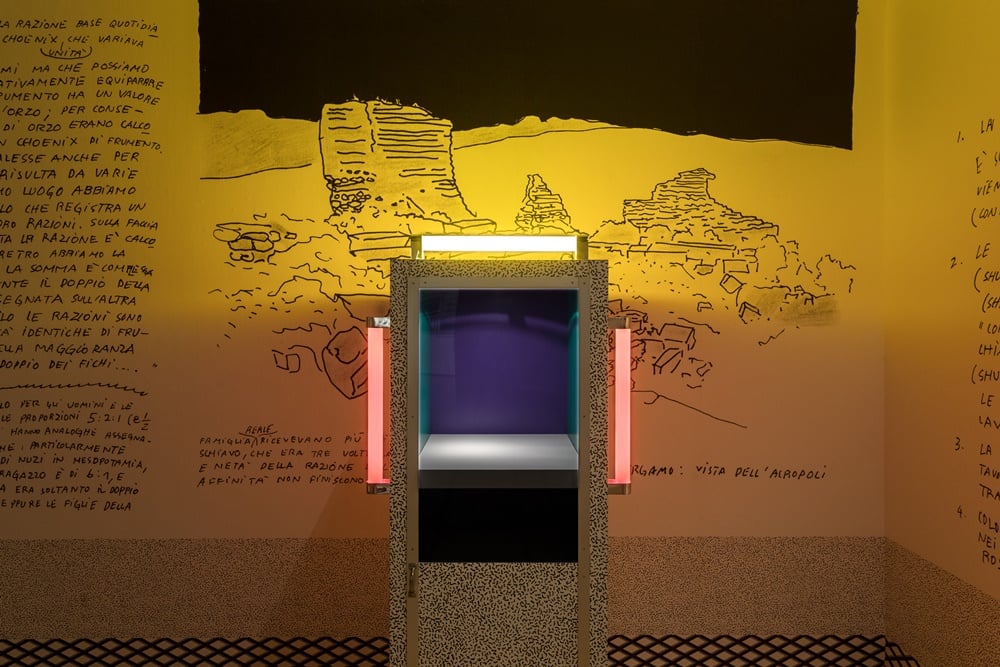

Installation view of “Ettore Sottsass: There Is a Planet” at La Triennale in Milan. ©Gianluca Di Ioia, courtesy of La Triennale, Milan.

“Rather than enter into a constructive dialogue, for the past few months the curator chose to conduct the conversation about this exhibition in an adversarial and divisive fashion,” they said, referring to Ingeborg de Roode, the museum’s industrial design curator of 17 years.

Both sides note that Sottsass, who first became involved with the museum in 1968 when his work was included in the show “Designers,” had enjoyed a fruitful, decades-long relationship with the institution. He passed away in 2007. The Stedelijk has more than 80 Sottsass works in its permanent collection.

The conversations between de Roode and Radice started more than a year and a half ago, the curator told artnet News. Several agreements were in place, including numerous loans from both Radice and Mourmans, as well as a book with texts by Sottsass that had never been published in English, and a contribution by Radice, de Roode said.

But after Radice curated a show of Sottsass’s work for La Triennale in Milan (on view through March), she insisted that the Stedelijk adopt a similar chronological format, according to de Roode, who had been planning on a thematic format instead.

In September, “for the first time she began to tell us that she didn’t want to have a thematic concept, which I had talked with her about and emailed her about already several times,” said de Roode. Radice also did not want to allow work by other designers to be in the Stedelijk show, de Roode said.

Mourmans and Radice have a different version of events, asserting in their statement that the curator “refused to detail her curatorial outline of the exhibition and her choice of works until a late date.”

In a subsequent phone interview, Mourmans told artnet News that it was he who was the main point of contact with the Stedelijk about the show for roughly the past 15 years—”not about a year and a half.”

“We never got a list of pieces she wanted to show. We never had a plan of the exhibition,” he said.

De Roode says she believed it was crucial to show not only the continuing themes in Sottsass’s work, which he addressed in a variety of media, but also the influence of his practice on younger designers, including the Memphis Group, which he started when he was nearly 65, often working with designers in their 20s and 30s.

Mourmans countered this, saying there was not a problem with a thematic exhibition—there was a problem with “that thematic exhibition.” When asked for specifics, he added: “Ask her the themes she sent on to Barbara Radice, not the ones she’s making up now.”

The Stedelijk and Radice agreed to part ways last fall and de Roode says she sought out other loans to replace ones that would not be supplied by Radice and Mourmans. She was able to secure loans from 30 other institutions and private collections, and Radice allegedly told her she would not “work against” the Stedelijk.

But as the museum attempted to go ahead with the show “it became very clear that they were really going to work against us,” de Roode said. “They were telling people not to work with us. They even went to a Dutch newspaper in the beginning of November to tell them that they really could not work with us. Still we tried to keep on talking with them.”

Installation view of “Ettore Sottsass: There Is a Planet” at La Triennale in Milan. ©Gianluca Di Ioia, courtesy of La Triennale, Milan.

Earlier this month, Sieburgh and the Stedelijk’s head curator, Bart van der Heide, traveled to Milan to meet with Radice. “It became clear to him that this opposition was getting really serious,” de Roode says. “We decided because of this to cancel the show. We did not want to make a show under these circumstances. Also we were working with many lenders and we didn’t want to put them in a problematic situation.”

Mourmans confirmed the Milan meeting but said that the museum still supplied no plan for the show nor a list of works they wanted to include at that time. “We didn’t dictate to them what to do,” Mourmans says. “We only said, you could take over this show from Milan.”

De Roode says the Milan show is not representative of Sottsass’s career, citing its lack of industrial design, contextual information, and “too many late pieces by Gallery Mourmans.” Citing Sottsass’s outsize fame in Italy, “it’s not an exhibit that would be fit for a Dutch audience.”

Mourmans says the Milan show was never meant to be a representative retrospective but instead was based on one of the artist’s ideas: “We don’t want to call it a retrospective because there are so many pieces missing. And we only had 1,500 square meters” to work with.

De Roode says the heart of the matter is about “the independence of the museum. There has been a lot of discussion recently about the relationship of museums and the art market or other outsiders. We cannot let them affect the way we do our shows.”