People

Why Stefan Simchowitz Is the Donald Trump of the Art World

They're both like a fictional bully out of a Hollywood blockbuster.

They're both like a fictional bully out of a Hollywood blockbuster.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

“Hey Butthead!” That signature line from the pursed lips of Biff Tannen of Back to The Future fame has, incredibly, shouldered aside common civics and spawned a pair of living, breathing imitators in both art and life.

Don’t believe me? Take it from Ted Cruz, who in a May speech pointed out the similarity between the fictional bully and the Republican Party’s candidate for President. After calling his primary opponent a “serial philanderer,” a “pathological liar” and a “narcissist,” Cruz regaled a crowd in Indianapolis with the latest instance of life imitating art that has already parodied life (in our copycat age, the feedback loop seems to never end).

“If anyone has seen the movie Back to the Future Part II,” Cruz raged in his best adaptation of an angry Billy Graham, “the [movie’s] screenwriter says that he based the character of Biff Tannen on Donald Trump, the caricature of a braggadocious, arrogant buffoon… We are looking, potentially, at the Biff Tannen presidency.”

For those not familiar with the Back to The Future trilogy—our age’s Wagnerian Ring Cycle—here is the plot of Part II in a nutshell. In the movie, Biff uses the profits from his Las Vegas-style casino to shake up the Republican party before pursuing political power himself, whereupon he transforms the idyllic town of Hill Valley, CA, into a dystopia of crime, corruption and profiteering—all while encouraging people to call him “Hill Valley’s number one citizen” and “America’s greatest living folk hero.”

Fast forward from 1989’s Back to the Future Part II to the future—our present—and one encounters the same kind of topsy-turvy, self-serving, say-anything to get ahead pseudo-logic. It is the rationale of pure power, the sort of bullying bluster that pokes fun at professional women and disabled journalists, picks fights with Gold Star families, impugns a sitting president as the “founder of ISIS,” glibly recommends violence to protect the Second Amendment, and generally treats the social contract, not to mention the US Constitution, with the decorum of Charmin Ultra Strong.

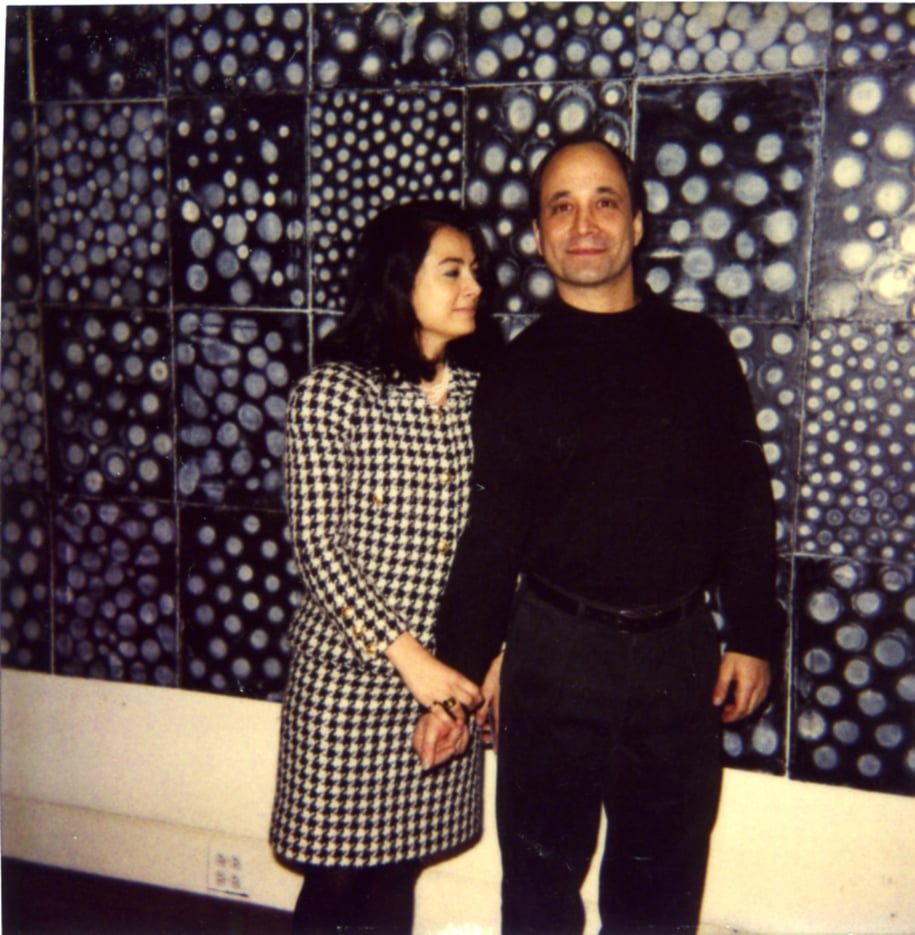

Mary Boone and Ross Bleckner circa 1991. Courtesy of Mary Boone.

But if presidential candidate Biff Trump has raised political power’s finest syllogism—Because I can—to new heights as performance art, how are all-important civics faring currently in art’s own Hill Valley?

One simple answer is that the art world now resembles Game of Thrones. Consider Mary Boone’s alleged swindle of actor Alec Baldwin. He claims that she duped him into buying a $190,000 Ross Bleckner painting resembling the one he wanted. Then there’s the summary firing of more than a dozen workers who tried to unionize at Jeff Koons’ mammoth studio (as Art F City pointed out, termination as punishment for trying to unionize, if proven, constitutes a violation of the National Labor Relations Act). And there are, of course, the hundreds of unconscionable staff cuts at perpetually expanding, multimillion dollar institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, MoMA, and the Brooklyn Museum, not to mention the steady bleed of departures at Christie’s and Sotheby’s.

Factor in this decade’s boom in art crimes, which the US Department of Justice currently ranks as the third-largest criminal enterprise in the world, and you have an angry, eye-gouging garden of frigs and frights that should look positively medieval to anyone willing to take the requisite step back for perspective. Make no mistake, entropic Hill Valley is not just an absurdly apt metaphor for America today, it is the perfect Boschian landscape portrait of our art town.

If that picture of the global art community could talk, it would croak the language of finance capital—in fluent Dothraki.

Artist Jeff Koons poses for a portrait for the media in front of his work Moon (Light Pink) during a media preview of his retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art on June 24, 2014 in New York. Photo: Andrew Burton/Getty Images.

Which is, frankly speaking, the lingo increasingly selected by the rich and powerful to conduct art world interactions which have—surprise!—grown more opaque by the year.

Whether the subject is straight up commerce, museum growth or the increasingly narrow pathways open to artistic success, the arguments brandished by art’s power players, and those who imitate them, tend ever less to solid notions of the common good (e.g., philanthropy, support of public institutions, financial transparency, collecting as opposed to buying, the long term health of the business of art) than to winner take all schemes with short-term returns (e.g., venture philanthropy, private museums, the abuse of art as a tax loophole, brazen speculation, and activist investing in the auction houses).

Like in presidential politics, the art world has even developed its own caricatures in the process.

Stefan Simchowitz at SOHO House on June 9, 2004 in New York City. Photo courtesy of Thos Robinson/Getty Images.

Enter art collector/dealer/flipper extraordinaire Stefan Simchowitz, a man who has been alternately called “the art world’s patron Satan” (according to Christopher Glazek in the New York Times ), “a Sith Lord” (by Jerry Saltz in New York) and, most recently “the Donald Trump of the art world” (per Sarah Thornton’s introduction at an April panel in Los Angeles).

Simchowitz—like Tannen and Trump before him—relishes portraying himself as a controversial actor, a “disruptor” in today’s co-opted countercultural lingo; or, using his own brand of doublespeak, a heroic figure ready to “initiate the paradigm shift” towards “this sort of ideology I invented” wherein art is “oil in the ground” that “needs to be mined, refined, and … distributed.” Unpack Simchowitz’s capsized meanings and a smoke-filled vision of environmental despoliation emerges: cultural production as fracking.

No less important for being generally considered a minor predator in an art pool teeming with much bigger sharks, Simchowitz’s is presently the loudest voice in the room arguing for the application of a model of pure finance in the art world. Among other methods to fast-track his young artists into the market, the dealer-collector has been known to defend flipping as a practice and to embrace social media as a shortcut to gallery and museum exhibitions. Like Trump’s insistence on building a border wall, Simchowitz’s demand to reduce art to pure profit margins is both outrageous and impossible, at least in the near term. Here’s another way to think of the South African-born art flipper: He’s a bullhorn with the build of Henry Kissinger—who, predictably, likes to go shirtless.

In a recent artnet News interview, this Biff Tannen/Donald Trump clone engaged in verbal jiu-jitsu with this publication’s Henri Neuendorf, ostensibly to insist that galleries quit protecting their artists and sell prized works to rank speculators like him. To make his point, the LA-based art flipper argued against existing collector hierarchies while peddling his exclusively mercantile view of art sales as a model of “cultural distribution,” an example of “democratized” culture, and even of “good business practices.” This Nietzschean transvaluation of values is not unlike the fictional Biff Tannen’s dream of turning Hill Valley’s “dilapidated courthouse into a beautiful casino hotel” or Donald Trump’s once successful, now disastrous electoral strategy of making America hate again.

As Simchowitz himself once put it in a Facebook post: “You need big balls in the art business nowdays [sic].” At the risk of being trolled ad nauseam as a “butthead” on social media, it’s time to speak plainly. Big balls won’t cut it in either in art or politics today, and making that fact crystal clear is the first step in pushing back against today’s transactional tide of mean.