Art & Exhibitions

How Europe’s Oldest Arts Festival Is Confronting the Rise of Nationalism

Set in the Austrian city of Graz, the arts festival Steirischer Herbst will try to delve into populism's grey zones.

Set in the Austrian city of Graz, the arts festival Steirischer Herbst will try to delve into populism's grey zones.

Kate Brown

Around a month before the opening of Steirisches Herbst, an arts festival which takes place in the picturesque Austrian town of Graz every September, the event’s new director and chief curator Ekaterina Degot was reading the news that Vladimir Putin’s private jet was pulling into city’s airport. “Why is he here?” the Russian curator asked herself.

Putin wasn’t in Graz for the festival, of course—he was there to attend the wedding of Austrian Foreign Minister Karin Kneissl. But as Degot now prepares for the festival’s hot-button exhibition, “Volksfronten” (or “People’s Fronts”), opening this Thursday, she thought that it was an uncanny coincidence that Putin should have showed up in August. After all, the Russian president has become an emblem of strongman politics and brazen nationalism and Degot was launching an intensive, month-long show set to tackle the complexities of Europe’s nationalist resurgence. “This creates an interesting situation for me,” she thought.

In part, that’s because Degot is the festival’s first non-Austrian leader. She is also its first non-German speaker. And the appointment of a foreigner for a five-year tenure at the prestigious festival comes at a time of particular tension for the nation. In national elections last winter, the conservative People’s Party rode a hard-line position on immigration to victory and then formed a coalition government with a far-right nationalist party that embraces an even more draconian position.

It’s unsurprising then that “Volksfronten” will offer a deep-dive into the troubling political climate across Europe. Some 30 artists and collective projects have been realized for the performance-heavy show. Most are new commissions—ranging from music to site-specific installations—that tackle the social and political narratives of the city as a “border” town that nears onto Eastern Europe. In keeping with its title, the show will have many “fronts,” as the team has chosen to set it across multiple locations for the first time.

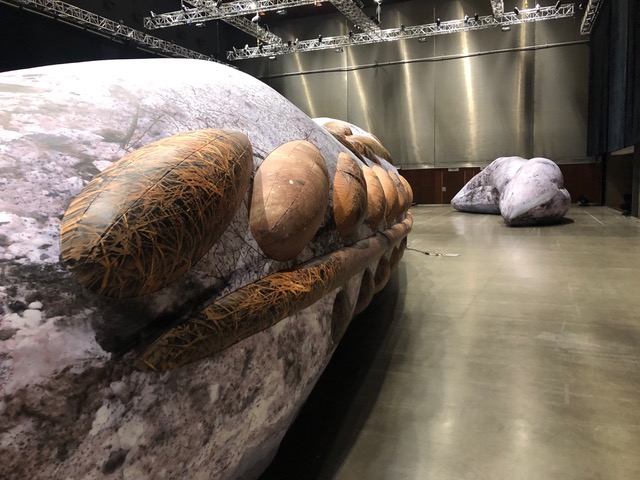

Details of installation of Irina Korina’s work Schnee von Gestern, 2018, at Helmut List Halle in Graz. Foto: steirischer herbst

“We are dealing with the normalization of nationalism everywhere,” Degot told artnet News. “One has to strongly oppose it, by reflecting on it intellectually but also by opening up spaces of alternatives through artistic imagination.”

Putin’s presence in the country last August may have been rare, but it wasn’t strange. The German-speaking nation has deep and enduring ties to the former Soviet nation, and as Degot points out, the current uptick in nationalist sentiment in Austria and Europe is not unrelated to the de-communization of Europe after the fall of the Soviet Union. “The nationalisms and racisms [we are seeing] are certainly rooted in this ridding of the communist past, and how this went wrong,” the curator explained.

The contemporary art festival, which began in 1968 and is Europe’s oldest, has long been known to shake things up for the otherwise quiet city. For Degot’s edition, the curatorial team aimed to bring the works directly to the public, and many of the pieces will unfold on public sites.

One of the first on the bill is Graz’s central station, Europaplatz, which will be the starting point for a parade by the legendary New York performing group Bread & Puppet Theater as a part of its opening weekend. The evening culminates in a stage production by the Slovenian musical provocateurs Laibach, who are revising the classic film The Sound of Music, as a counterpoint to the original’s simplified treatment of Austria’s dark history.

Installation works for ZIP group, Aurora, 2018, on 17. September 2018 on the roof of Arbeiterkammer (Chamber of Labour) Graz. Foto: Clara Wildberger

Text says: “Death to fascism, freedom to the people.”

Degot explains that the film, in which Christopher Plummer plays a “good” Austrian—a nationalist himself but one who opposes the Nazis—is “a very American postwar interpretation.” The curator points out that no one really knows the film in Austria. “[It] has nothing to do with reality. But this story is important because it tells us how contemporary times may reinterpret fascist history: Being a nationalist is something good in this musical.”

Many other works provide revisions of Austria’s self-identity and history. Moscow-based artist Irina Korina will present a massive environment that explores the idealistic connections drawn between nature and nationalism. East German-born artist Henrike Naumann will launch an installation as a design store that builds an alternative picture of 20th-century Austria. And artist Milica Tomić, born in the former Yugoslavia, is revisiting a World War II forced labor camp near Graz, reinterpreting it as a forensic research installation.

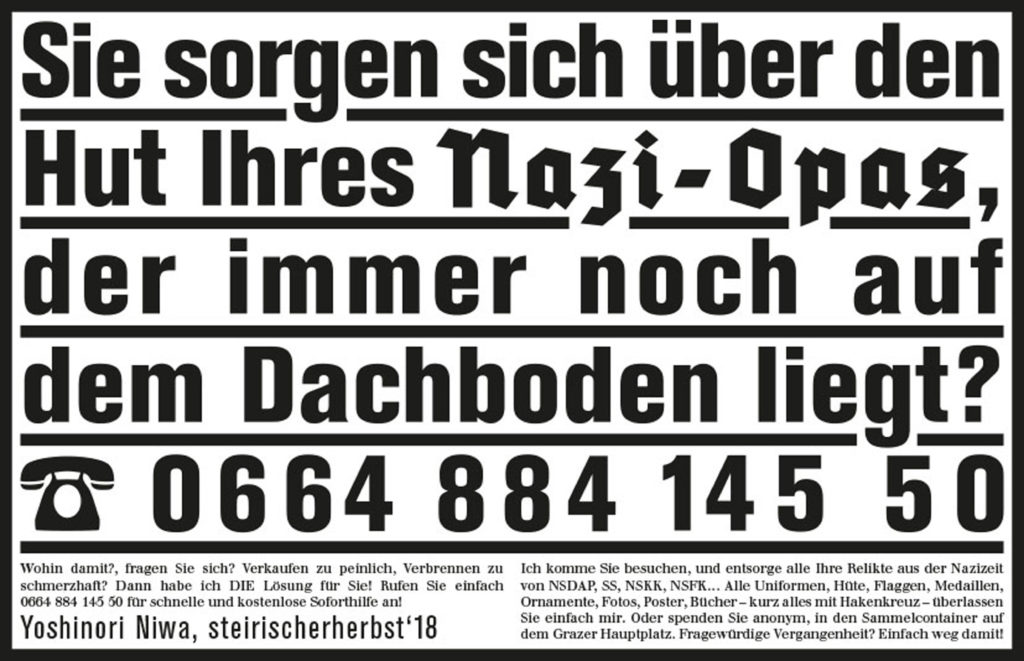

There will also be projects located in public space that address Austria’s own Nazi past. Japanese-born, Vienna-based artist Yoshinori Niwa’s ongoing project, Withdrawing Adolf Hitler from a Private Space, does that quite literally. The artist is inviting locals to donate any Nazi paraphernalia that they may still have in their family. Interested parties have been leaving their contact info for Niwa to visit them before gathering the items, which will be showcased in a public display. It will stand in a container in the center of town before being destroyed towards the end of the festival. Normally, displaying Nazi emblems of any kind is completely illegal, but the artist is working with officials to create an exception for the work.

Yoshinori Niwa’s advertising campaign for Steirisches Herbst.

“The situation of negotiating Nazi history here is very specific, and I met many people who said they don’t know what to do with these objects,” Degot says of Niwa’s project, which has included an ad campaign to let locals know they can donate to the project. “They don’t want to destroy it themselves because there is something related to their relatives perhaps, but they are also ashamed to keep it. It’s an issue for many people, just like it is an issue for Austria in general for not having dealt with their Nazi past.”

When asked if she thinks there is a possibility that Niwa’s work could become a gathering hub for Neo-Nazi gathering, Degot wasn’t worried. Neo-Nazis, she said, have other places they can gather. The curator is more concerned with the artwork itself. “It makes me concerned if an artwork can be removed because it causes controversy,” she said. “Under current conditions, I don’t know how many of the greatest artworks of the past would have been possible. Isn’t it the role of art to create controversies? One cannot have secure art.”

Steirisches Herbst opens on September 20 at various locations in Graz, Austria. For more information about their program, artists and speakers, visit their website here.

Victoria Lomasko, drawing from Other Russias, 2017. Kapitalina Ivanovna: “Lenin lives! It’s what I live for!” Courtesy the artist.

Lars Cuzner’s The Intelligence Party (2018).

Ines Doujak, Economies of Desperation, 2018, collages. Courtesy the artist.