Artists

Step Inside the Fantastical and Frightening World of Indonesian Artist Natasha Tontey

Her new exhibition “Primate Visions: Macaque Macabre” is now on view at Museum MACAN in Jakarta.

Her new exhibition “Primate Visions: Macaque Macabre” is now on view at Museum MACAN in Jakarta.

Cathy Fan

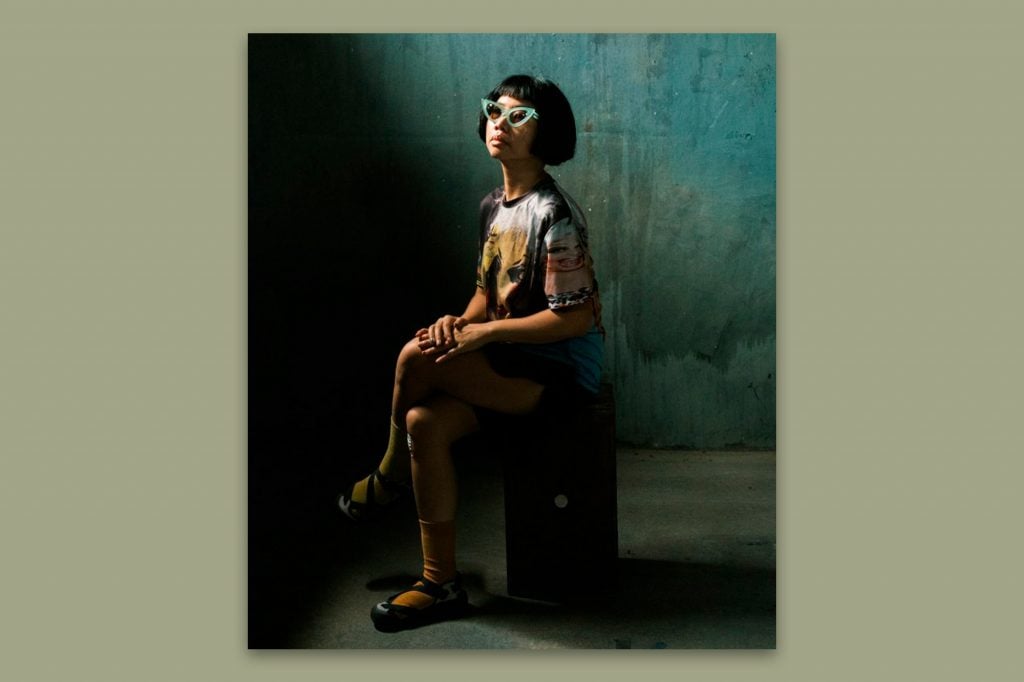

What’s the best way to describe the work of buzzy Indonesian artist Natasha Tontey? Quirky, bizarre, retro, contemporary, absurd, critical, subversive, and kitschy all come to mind, and yet none alone encapsulates the 35-year-old artist’s marvelous strange approach to artmaking.

During the opening of her new museum show, Tontey (b. 1989) was impossible to miss, with her glossy bob haircut, and wearing cat-eye sunglasses and a ’60s vintage dress. She is among Indonesia’s most prominent young artists. Her new exhibition, “Primate Visions: Macaque Macabre” now on view at Museum MACAN in Jakarta, further cements her status (Audemars Piguet commissions the work).

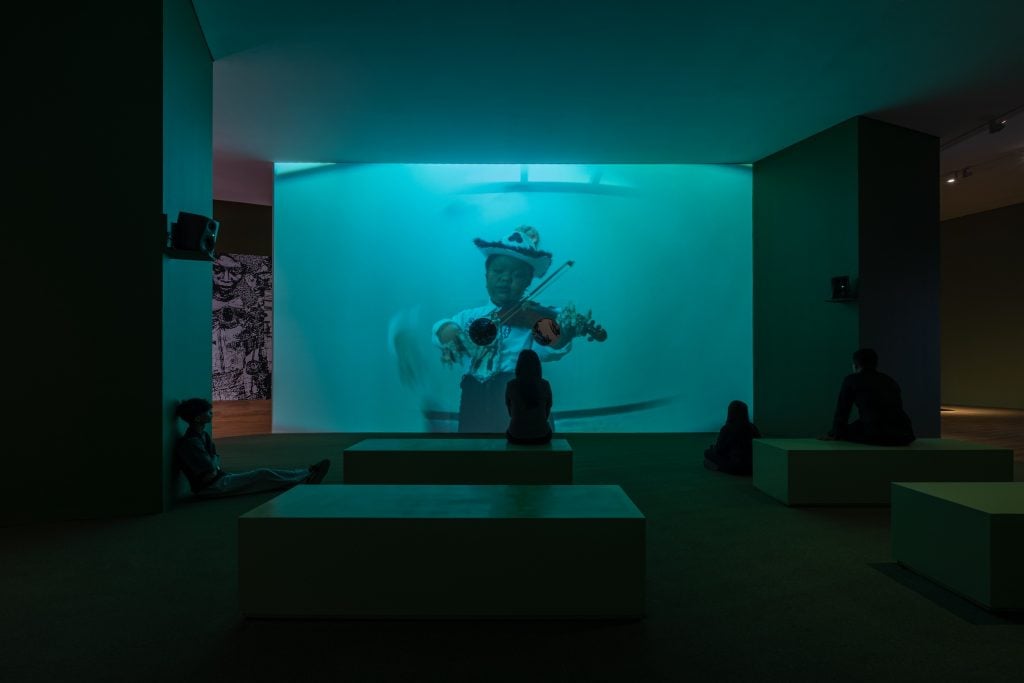

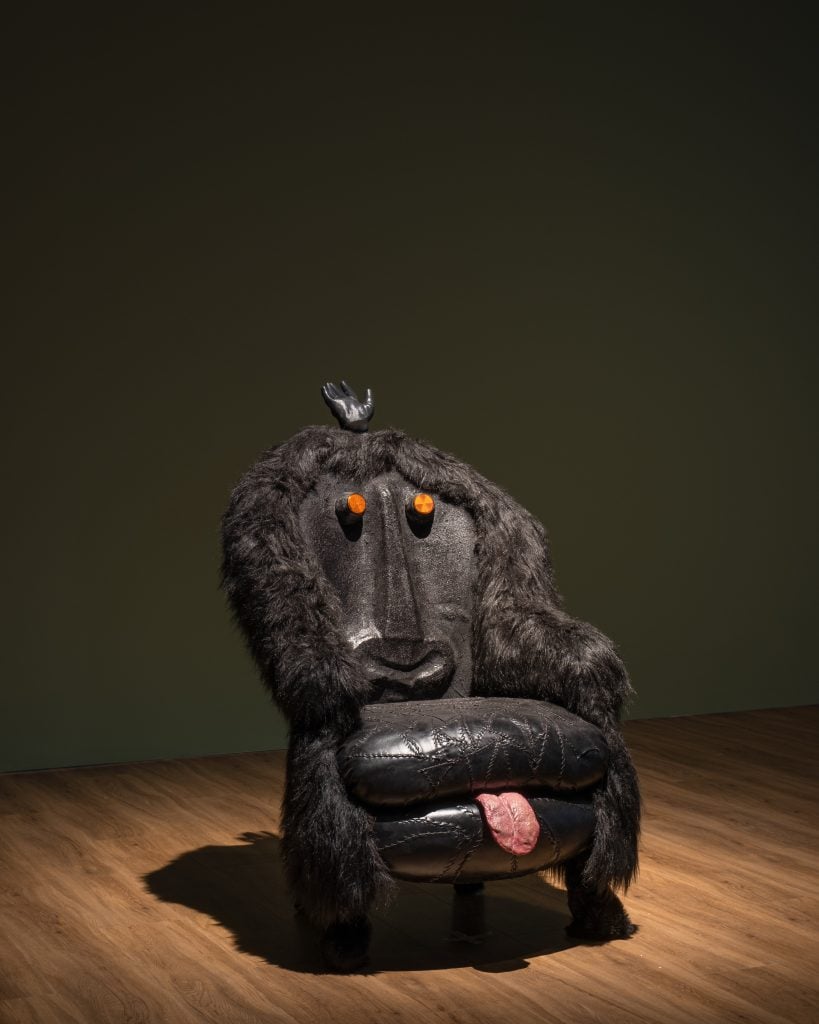

Installation shots of “Primate Visions: Macaque Macabre”, by Natasha Tontey, at Museum MACAN. Commissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary. Courtesy of the artist and Audemars Piguet

Not long after the museum show opened, the Han Nefkens Foundation announced that Toney had won its annual Video Art Production Grant. Yet, to date, the artist has not chosen to sign with a gallery. “I am not really sure about the commercial game,” she confides during the exhibition, saying it’s a way to maintain her independence as an artist. However, she occasionally takes on suitable side hustles—she once even owned a fashion brand.

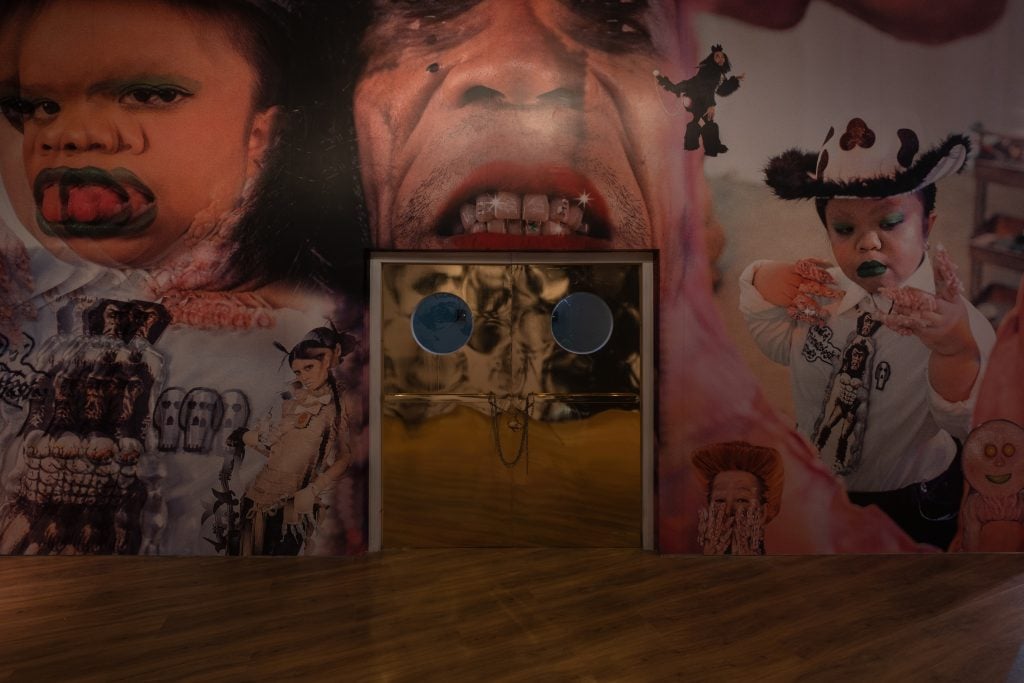

And Tontey is certainly independent. Few exhibitions invite you to enter through a macaque’s rear end, but “Primate Visions” does. Visitors are invited to step into the dark, prehistoric cave through a red, furry pair of “buttocks”—a deliberate design choice by the artist—that takes visitors into an immersive world she has created.

If this approach raises questions, more answers await in a film that serves as the centerpiece of the exhibition. It’s a work inspired by the dramatic style of 19th-century French theater, brimming with dystopian aesthetics and infused with B-movie and horror elements. Yet the film is also comical, recalling the low-budget skits of television variety shows.

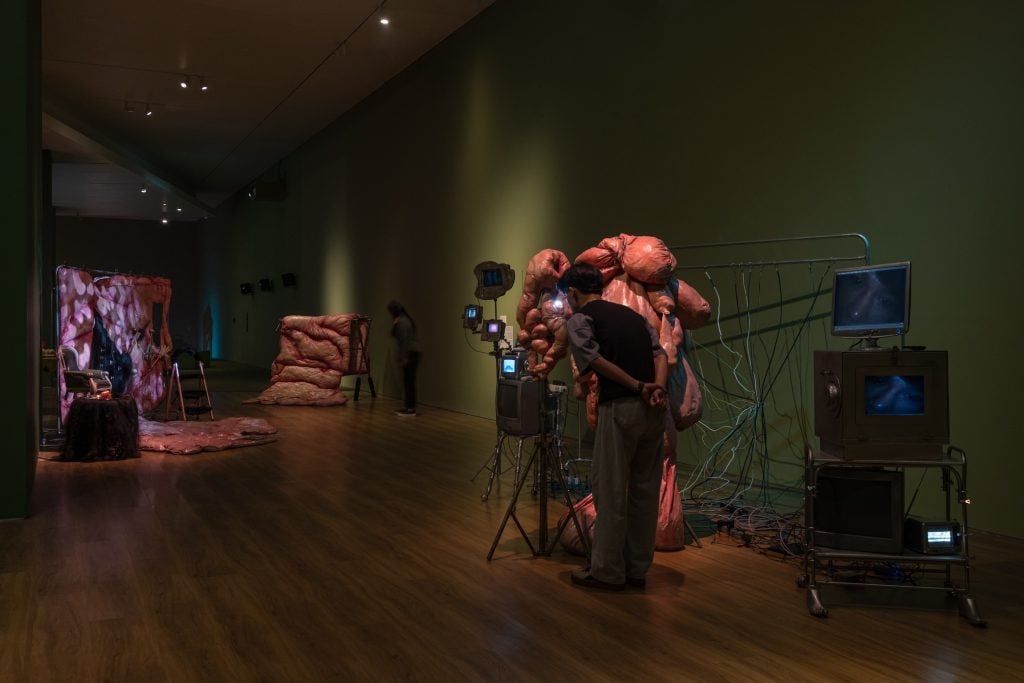

Installation shots of “Primate Visions: Macaque Macabre”, by Natasha Tontey, at Museum MACAN. Commissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary. Courtesy of the artist and Audemars Piguet

The film’s protagonists are two female primatologists who rescue two captive macaques, a species of monkey, and release them into the wild. Along their journey, they experience surreal adventures: attending a special dinner to eat a pudding that grants immortality, visiting a biomedical research facility, traveling through a prehistoric cave (the same one visitors entered the exhibition through), and finally returning to the Minahasa Peninsula on Sulawesi, one of Indonesia’s largest islands. In the film, the macaques emerge from their habitat and raise this humorous yet challenging question. For instance, consciousness is often thought to originate in the brain, but what if the world we imagine begins from the bottom?

One character in the film, Xenomorphia, has a long tail made of bones and macaque skulls—a nod to the traditional warrior costumes of Minahasa. The character possesses both human and macaque features, and its name reflects both its hybrid nature and ideas of xeno-feminism. Throughout the film, Xenomorphia urges viewers to consider similarities and differences between species.

The film’s screening creates a sense of unease among viewers, partly due to two large circular holes cut into the projection screen. Looking through them from behind reveals the laboratory doors depicted in the film. Denis Pernet, Curator of Audemars Piguet Contemporary, describes this as Tontey’s way of integrating “everything into her fantastic magic world.” The holes disrupt the classic screen-viewing experience and invite a “strange relationship” with the projection. “We look at the macaques, but the macaques also look at us. They have their own train of thought. What could be the point of view of a macaque?” Pernet puts it, “Maybe these holes invite us to rethink our relationship with them. You are looking at the screen, but someone is also looking at you watching the screen.”

Behind the scenes of Primate Visions: Macaque Macabre, by Natasha Tontey commissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary. Courtesy of the artist and Audemars Piguet

The film’s scientists, wearing cowboy hats, break away from stereotypical images of scientists. One of their shirts is emblazoned with the words “Primate Visions,” paying homage to the namesake of Donna Haraway’s book. This cultural fusion is a hallmark of Tontey’s work. Minahasa, where traces of colonial history remain, is a recurring interest for her.

In the film, John Denver’s Take Me Home, Country Roads plays—a song widely popular in Minahasa. This peninsula, located in northeastern Sulawesi, is where the Sulawesi and Maluku seas meet. Yet Tontey grew up amid the towering buildings and bustling streets of Jakarta and, as a child, paid little attention to her Minahasan heritage. “As I grow up and get wiser, my vision has changed how I perceive my ancestral knowledge,” she reflects at the exhibition. “I’m sorry for being ignorant, but now I’m really into it.”

Now based between Jakarta and Yogyakarta, Tontey has chosen to reconnect with her roots in Minahasa, frequently interacting with local communities. She explores indigenous cosmology, delving into human relationships with nature and non-human entities. She describes the human-macaque relationship as “chaotic yet tightly intertwined,” which is also a central theme of this project. “The exhibition aims to showcase and validate the complex, often contradictory relationship between humans and macaques,” she says. “Through a fictional narrative, I want to tell a story about primatology, ecofeminism, and the dynamics of technology.”

Installation shots of “Primate Visions: Macaque Macabre”, by Natasha Tontey, at Museum MACAN. Commissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary. Courtesy of the artist and Audemars Piguet

Installation shots of “Primate Visions: Macaque Macabre”, by Natasha Tontey, at Museum MACAN. Commissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary. Courtesy of the artist and Audemars Piguet

Black-crested macaques, a recurring presence in her work, are large and fluffy creatures. Known locally as yaki, they have shared the Minahasan land with humans for centuries. While sometimes viewed as pests for raiding crops, they are also regarded as lucky symbols, even inspiring traditional costumes at celebrations. In Minahasan cosmology, these primates are deeply intertwined with human destiny.

Costumes and props from the film are displayed throughout the exhibition, showcasing Tontey’s unique aesthetic system. For example, cages once used to hold monkeys are decorated with hair clips popular among young girls. The work blends Indonesian soap opera aesthetics, video game influences, and subcultures, creating a humorous yet kitschy effect. Tontey adopts this subversive approach to critique traditional masculinity while inviting a rethinking of myths and ancestral knowledge.

Amid this dark and fantastical world, an installation resembles a medical device with fleshy organic panels, some covered in hair, evoking discarded organs. The unsettling creation is inspired by endoscopic surgeries “performed by macaques” in the film, in which the artist imagines a voluntary collaboration between humans and primates.

Installation shots of “Primate Visions: Macaque Macabre”, by Natasha Tontey, at Museum MACAN. Commissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary. Courtesy of the artist and Audemars Piguet

Natasha Tontey and Denis Pernet. Courtesy of the artist and Audemars Piguet

During a guided tour, Tontey steps up to the camera, opens her mouth wide, and encourages viewers to become part of the “experiment,” exploring the microscopic world to uncover “each other’s souls or consciousness.” She offers another whimsical idea: “If consciousness doesn’t come from the brain but starts at the bottom (like the monkey-butt cave), then maybe the stomach could be another brain. They’ve got microbiomes and microcells—it’s just flipping things upside down. It’s very interesting.”

When asked about her priorities, Tontey shares, “I think it’s important to expand the idea that humans are not the center of the ecosystem and that we are not everything.” And she hints at an intriguing future project—next, she’ll be delving into Minahasa’s history of gangsters.