Artists

Love Letters Reveal the Passion and Turmoil of Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz’s Fiery Affair

In this edition of "Art Bites," we unpack the tantalizing correspondence that was made public 20 years after O'Keeffe's death.

Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe were not only exceptional artists, but prolific writers of love letters. The correspondence between these two spans 5,000 letters and 25,000 pages. Sometimes they wrote each other three times a day. Sometimes the letters measured 40 pages long. This great romantic archive was only made public in 2006—20 years after O’Keeffe’s death, and 60 years after Stieglitz’s—at the former artist’s behest.

Stieglitz first learned of O’Keeffe in January 1916, when she was teaching in South Carolina. A friend showed him a few of her charcoal drawings, and he was impressed. “Mr. Stieglitz: If you remember for a week—why you liked my charcoals that Anita Pollitzer showed you—and what they said to you—I would like to know if you want to tell me,” O’Keeffe wrote to Stieglitz that month.

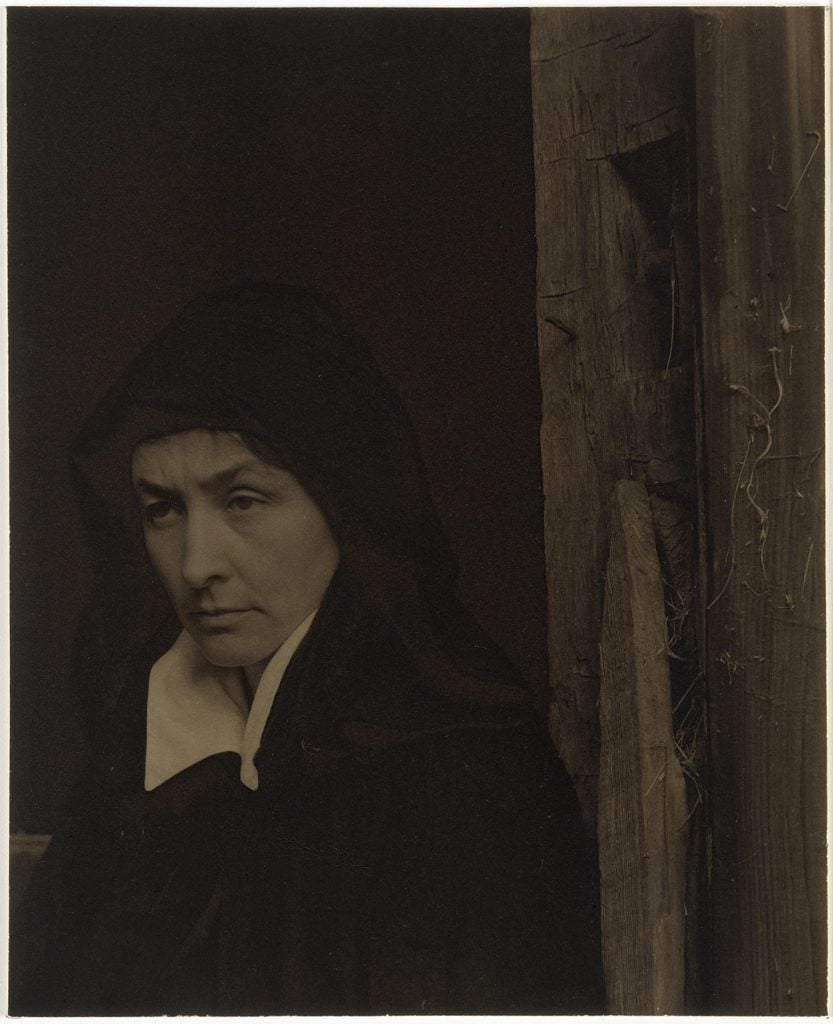

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe (in a chemise) (1918). Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa

Fe / Art Resource, NY.

“I am so glad they surprised you—that they gave you joy,” she wrote in February. By autumn, she was outright flirting with her new mentor, married and 24 years her senior, even exhibiting that hallmark of early love: the need to bare it all. “Having told you so much of me—more than anyone else I know—could anything else follow but that I should want you?” she wrote in November.

“My head would just about come to your knee if I were standing in front of you,” O’Keeffe teased in December. “Its great to be little—I like it.”

In April 1917, Stieglitz’s Gallery 291 staged O’Keeffe’s first solo exhibition. She showed up unannounced. In June, he wrote to her, :”How I wanted to photograph you—the hands—the mouth—& eyes— & the enveloped in black body—the touch of white—& the throat.” He started separating from his first wife. His daughter Kitty cut off contact.

In May 1918, he asked O’Keeffe to leave her then-home of Texas for New York. That same month, he wrote, “You are so much to me that you must not come near me—Coming may bring you darkness instead of light.” Nonetheless, O’Keeffe made the move, quickly becoming his closest muse, critic, and collaborator.

Cohabitation stymied their letters, but not their spark. “I am on my back—waiting to be spread wide apart,” O’Keefe wrote him from Maine in May 1922. “I could write about this all day.”

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe (1924). Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Stieglitz’s divorce was finalised in 1924, and he married O’Keeffe. Their relationship strained under marriage’s confines. In 1929, O’Keeffe discovered her husband’s affair with the young photographer and writer Dorothy Norman. That same year, O’Keeffe started summering in New Mexico.

Stieglitz didn’t like the distance. “I am broken,” he wrote. But, that first July, she assured that “what is between us is alright—and I don’t want you to worry a bit about me—There was much more cause to worry about things when I was right beside you.”

By July 1934, though, her tune had changed. “I do not for one moment accept the idea of your going about publicly making love to someone else,” O’Keeffe fumed. “I know that one can not control what one feels but one can control the public exhibition of it.”

Fortunately, they enjoyed a somewhat more placid period in the years before Stieglitz’s death, in 1946. O’Keeffe heeded a friend’s advice to send Stieglitz’s archive to Yale, to accompany works and artifacts from other important Modernist thinkers. She arranged to send her papers to join his after she died, stipulating the aforementioned 20 year moratorium. She framed their love in silence before the world could witness it.