Archaeology & History

A Stone Wall Submerged in the Baltic Sea Could Be Europe’s Oldest Megastructure

The "Blinkerwall" in the Bay of Mecklenburg is said to be over 10,000 years old.

The "Blinkerwall" in the Bay of Mecklenburg is said to be over 10,000 years old.

Tim Brinkhof

In 2021, researchers scanning the waters of Germany’s Baltic Sea coast discovered a giant wall submerged beneath the Bay of Mecklenburg. Now, a new study published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) suggests that this wall—roughly a mile and a half in length—could be the oldest manmade structure in all of Europe.

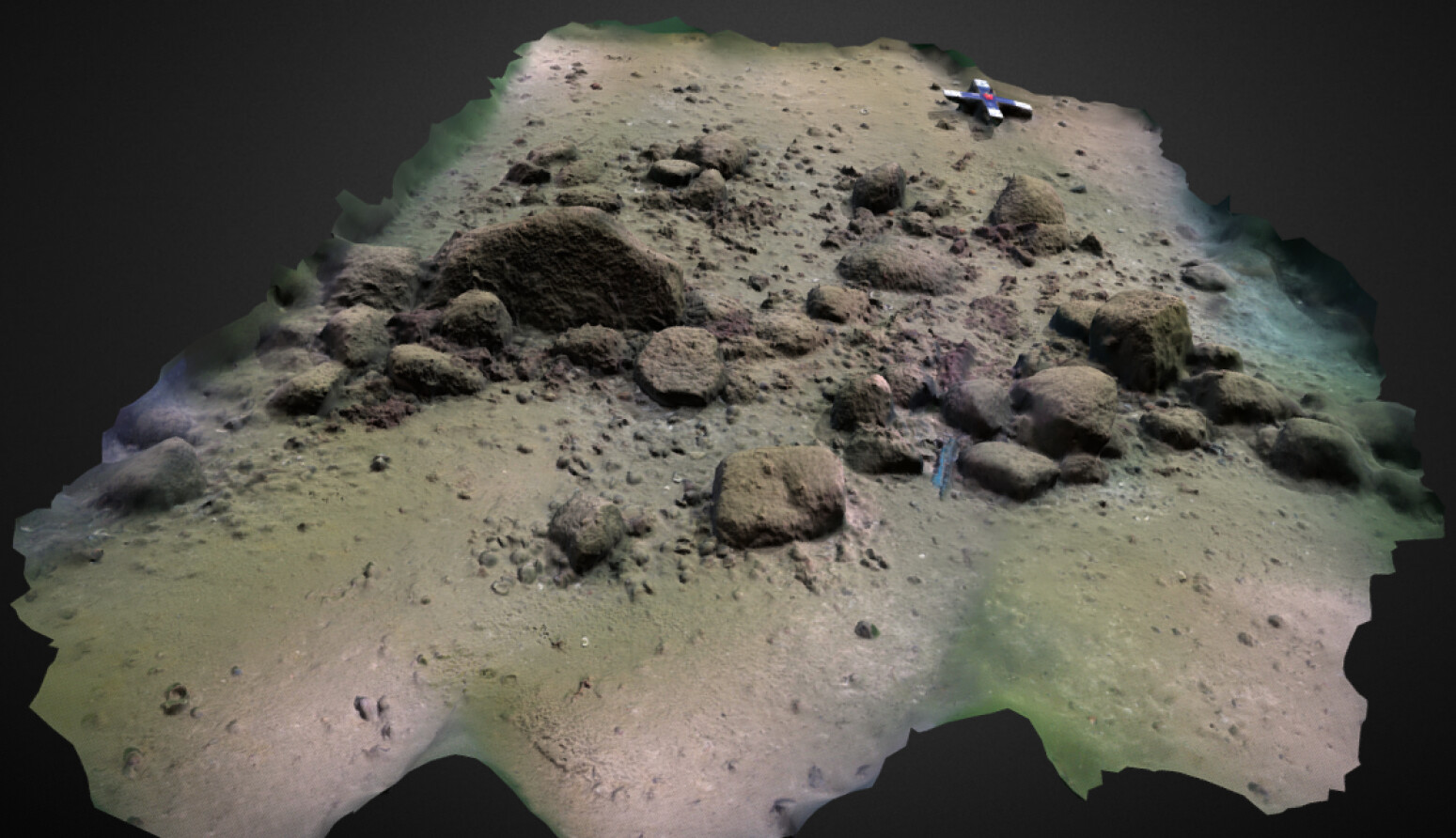

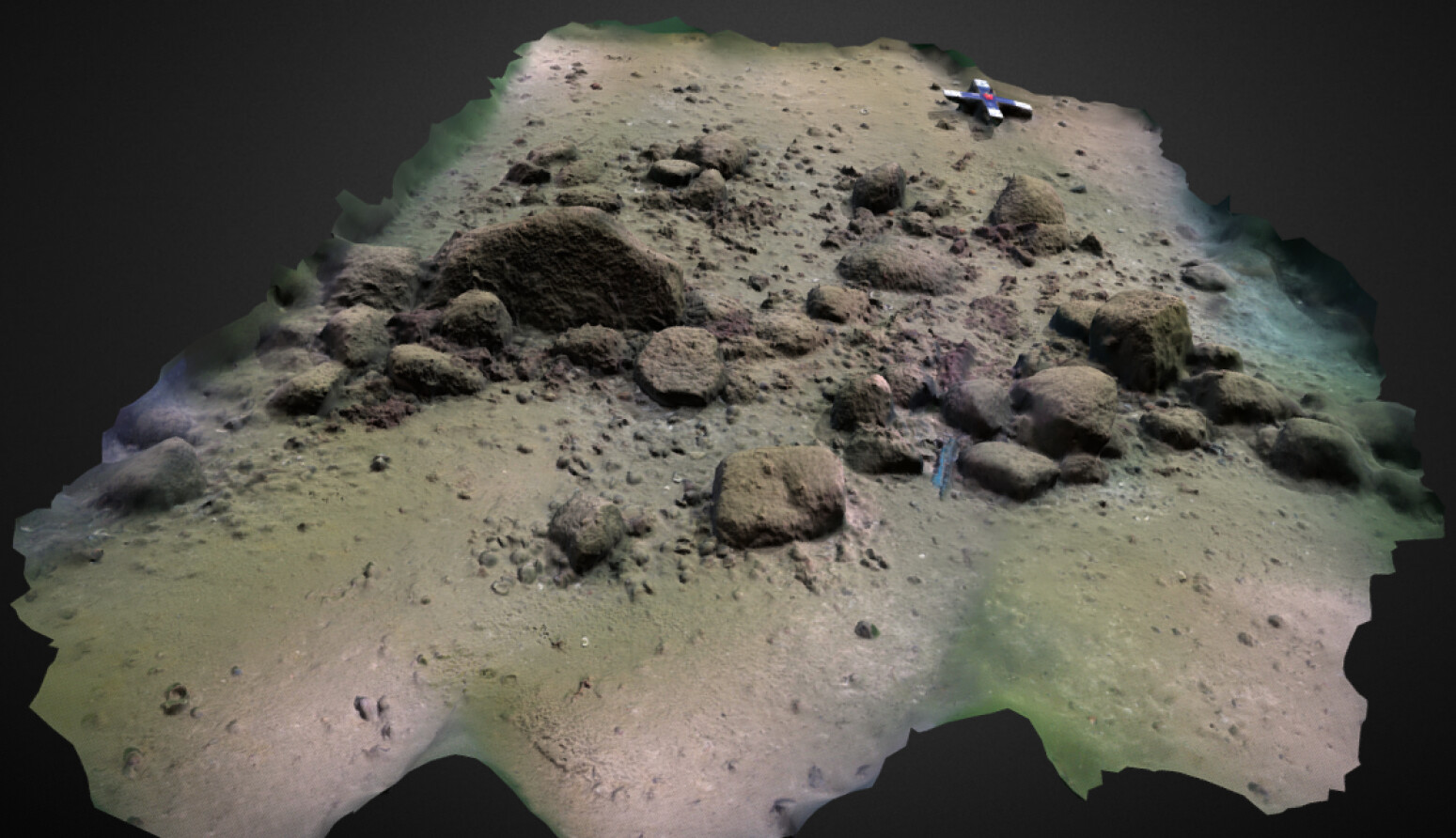

After traces of the subsequently named “Blinkerwall” showed up in high-resolution hydroacoustic imaging, a team of human divers went in for a closer look. Resting at more than 68 feet beneath the water’s surface, the wall turned out to consist of about 1,400 small stones connecting 300 large boulders.

A study led by scientist Jacob Geersen ruled out the possibility that the Blinkerwall was created through natural processes like eskers, tsunamis, or glacial motion, concluding it must have been put together by hunter-gatherers instead. Considering that some of the boulders weigh as much 142 tons, though, it’s still unclear how these ancient humans would have accomplished such a feat.

The wall’s age makes its origin story even more puzzling, with sediment dating indicating the structure to be over 10,000 years old, when the surrounding area still rested above sea level. This would make the Blinkerwall considerably older than other European megastructures such as the Carnac Stones of France or England’s Stonehenge, parts of which are thought to have been constructed between 3100 and 1600 B.C.E.

Equally ambiguous is the purpose the Blinkerwall would have served its mysterious creators. Geersen and co-authors speculate it might have functioned as a driving lane for reindeer hunters. “When you chase the animals, they follow these structures [and] don’t attempt to jump over them,” he has said. The wall could have forced the reindeer into a nearby lake, where hunters would have been able to easily take them out with spears and bows.

Work in the Bay of Mecklenburg is far from over, as the researchers suspect a second, possibly even older wall remains buried underneath the seafloor.