Archaeology & History

Researchers Say They’ve Discovered Stonehenge’s Real Purpose: To Serve as a Solar Calendar (It Even Factored in Leap Days!)

Each of the stones, and its formation, denotes a specific aspect of the calendar.

Each of the stones, and its formation, denotes a specific aspect of the calendar.

Caroline Goldstein

Stonehenge may finally be getting a little less mysterious.

Researchers have long thought that the prehistoric monument in Wiltshire, England, had some time-keeping purpose, but the exact mechanics of how it worked—and why—remained unclear. Now, a study published in the journal Antiquity sheds new light on the purpose the site may have served.

The study’s author, professor Timothy Darvill of Bournemouth University, proposes that the monument functioned as a Neolithic calendar. The largest stones, known as sarsens, hold the key to the structure’s use as the “building blocks of a simple and elegant perpetual calendar based on the 365.25 solar days in a mean tropical year.”

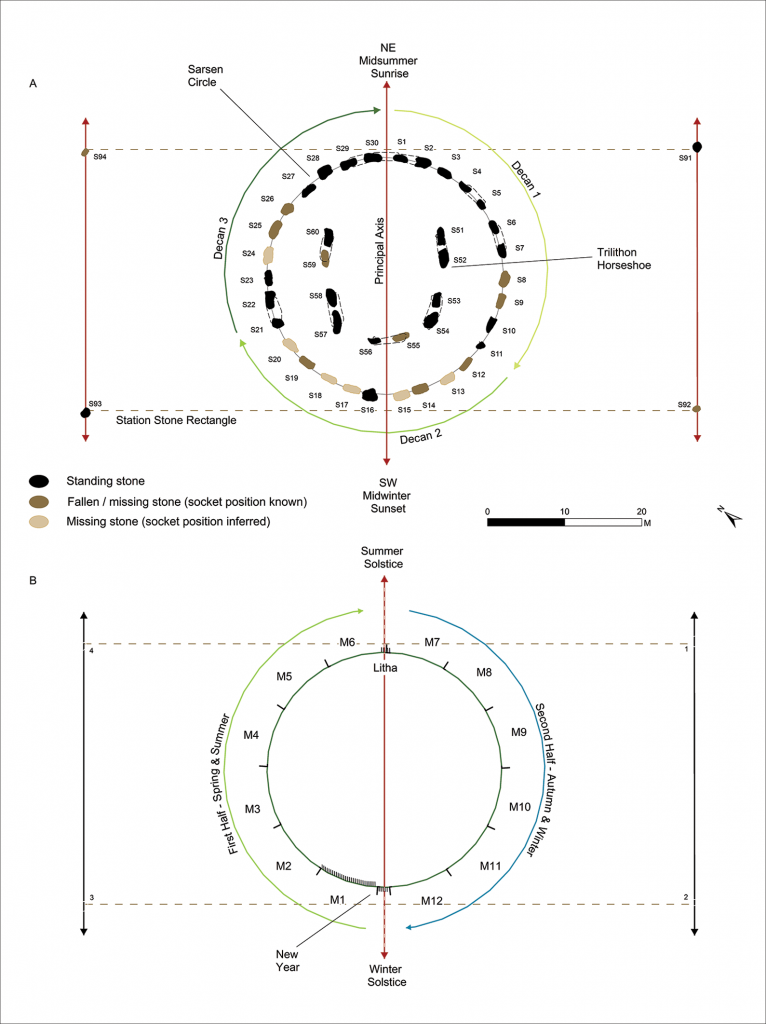

Experts determined that the sarsens that comprise Trilithons, Sarsen Circle, and the Station Stone Rectangle were all set up between 2620 and 2480 B.C., and never moved again. The Sarsen Circle, which is the most visually distinctive aspect of the site, is made up of 30 upright sarsen stones linked by 30 lintels at each top. The goal, Darvill says, was “to form a complete circuit.” (Darvill noted that some of the stones have fallen to the ground or are missing, having likely been stolen during antiquity.)

Summary of the way in which the numerology of sarsen elements at Stonehenge combine to create a perpetual solar calendar. (drawing by V. Constant) courtesy of Bournemouth University.

Darvill analyzed the stones—which were all sourced from the same area—and found that they corresponded neatly to the Neolithic calendar, which measures a month as 30 days, or three 10-day weeks. Each stone within the circle represents one day, numbering S1 to S30. Within the Sarsen Circle, the shapes of of S11 and S21 are anomalous, which indicate the beginning of the second and third weeks. A total of 12 monthly cycles—represented by the upright stones within the circle—adds up to 360 solar days.

The remaining five days that complete the basic tropical year are represented by the five stones that make up the Trilithon Horseshoe in the center of the monument. Organized from North to East, the stones are arranged from smallest to largest.

As it turns out, Stonehenge even accounted for leap years. The four Station Stones, organized in a rectangle around the perimeter of the main circle, allow for an extra day to be added to the intercalary (or leap) month every fourth year.

Courtesy of Timothy Darvill.

“Materializing a time-reckoning system in the structure and form of a major monument, with all the effort implied in doing so, should come as no surprise, for it is a common practice amongst non-literate and semi-literate societies,” Darvill said.

The calendar would have served a variety of purposes at the time, according to the author. It let farmers know when to celebrate the harvest festival, or honor certain deities. It also gave physical substance to cosmological beliefs, helped political elites concentrate their power (for he who controls time controls power), and brought communities closer to their gods by “ensuring that events occur at propitious moments.”