Museums & Institutions

How Storm King Art Center Became One of the World’s Top Sculpture Parks

The museum's open-air art, made by artists including Alexander Calder and Maya Lin, has brought it international recognition.

Once the New York art world’s best-kept secret, Storm King Art Center has exploded into popular consciousness in recent years. Suddenly, it seems everyone is making the short trek to the sprawling, open-air sculpture park just an hour’s drive north of the city in idyllic Hudson Valley country.

Poised to mark its 65th anniversary next year, Storm King has become perhaps the largest and most renowned outdoor sculpture park in the U.S. Steady growth and tireless conservation has led to a permanent collection of more than 100 works, spread out across 500 acres of lush fields and forests. Well-known artists such as Richard Serra, Alexander Calder, Louise Bourgeois, Isamu Noguchi, and Maya Lin, as well as more contemporary names including Sarah Sze, Rashid Johnson, Zhang Huan, and Ugo Rondinone have ensured a constant flow of wonderstruck visitors eager to trade the white cubes of Manhattan galleries for the green expanses of upstate New York.

Storm King’s president John Stern—whose father and grandfather co-founded the space in 1960 as a museum for Hudson River School paintings before widening the scope to include outdoor sculpture—is not surprised by the boom in attendance. “Storm King is the type of place where, if you’ve been, you love it,” he said in an interview. “Over the past years, we’ve grown our exhibitions and programming, so more and more people are realizing it’s like nowhere else they’ve seen.”

“The combination of art and nature at Storm King is unusual and invigorating,” agrees Nora Lawrence, the sculpture park’s artistic director and chief curator. She has the enviable job of working directly with artists in mapping out and installing their ambitious projects, often shaping the landscape to accommodate them. “Our site is not neutral or blank—it is an active participant in any installation,” she said. “We thrive on working with artists who specifically want their work to be located at Storm King.”

One of those artists is Arlene Shechet, who has just launched the 2024 summer season with six large, vibrant sheet-metal abstractions, as well as smaller ceramics shown in the indoor galleries. “The sculptures are intended to be seen across Storm King’s long distances,” said Lawrence. “They can all be seen with at least one other in your eye’s frame.”

On the eve of Storm King’s busiest time of year, we take a closer look at seven of its most beloved landmarks.

Alexander Calder, The Arch (1975)

Alexander Calder, The Arch (1975). © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Jerry L. Thompson. Courtesy of Storm King Art Center.

Known as the “sculptor of air” for his pioneering kinetic work with mobiles, Alexander Calder is just as celebrated for the monumental “stabile” sculptures that populated his late career. The Arch is one such work, among the last he created before his death in 1976, although it is based on a miniature model he conceived in 1940.

The Arch melds biomorphic and architectonic forms to create an imposing yet welcoming landmark, inviting visitors to pass through its portal on their way into the center. And they do, making this work one of Storm King’s star attractions.

Isamu Noguchi, Momo Taro (1977–78)

Isamu Noguchi, Momo Taro (1977–78). © 2021 The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Jerry L. Thompson. Courtesy of Storm King Art Center.

A big perk for artists working with Storm King is that they are given all the time and space they need to execute their projects. “When my father was working with Isamu Noguchi on his commission,” recalled Stern, “the artist asked, ‘When do you need it?’ and my father replied, ‘When it’s finished.’”

After that meeting, Noguchi returned to his studio in Japan and began work on what would become Momo Taro. The nine-part, 40-ton granite behemoth was born from the cleaving of a boulder that his assistant found on a nearby island, but which was too large to move whole. By splitting it in two, the assistant was reminded of the Japanese folk hero Momo Taro, who, according to legend, was born from a giant peach pit.

Momo Taro’s hollow interior—its peach pit—has beckoned throngs of children over the years to climb inside, just as Noguchi wanted. The ensuing photo ops, Stern said, have made the crowd-pleaser one of the most photographed works at Storm King.

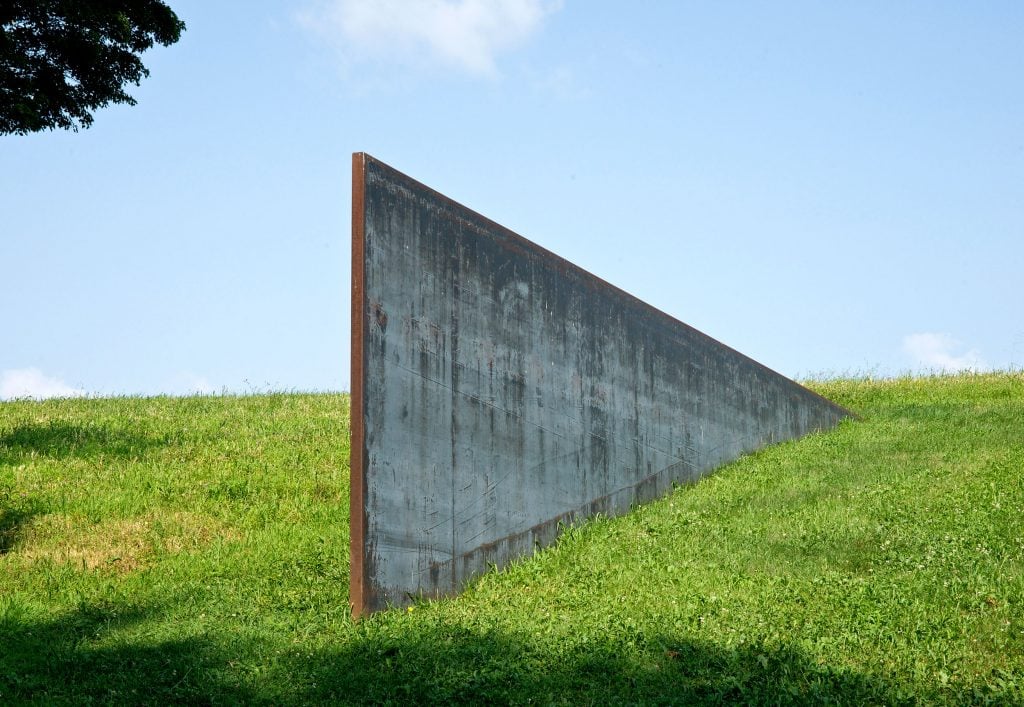

Richard Serra, Schunnemunk Fork (1990–91)

Richard Serra, Schunnemunk Fork (1990–91). © 2021 Richard Serra / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Jerry L. Thompson. Courtesy of Storm King Art Center.

After consulting topographical maps and even enlisting a surveyor to appraise the park’s landscape, Richard Serra chose a ten-acre field at the far southern edge as the site for Schunnemunk Fork. The colossal work of land art has been synonymous with Storm King ever since.

“It’s breathtaking,” exclaimed Lawrence. “He created the large-scale work by using four straight lengths of weathering steel to magnificent effect.” The artist chose to bury the majority of the plates—each measuring up to 55 feet long—in the ground. As such, attention is focused less on the sculpture than its relationship to the land, the viewer, and the view of Schunnemunk Mountain in the distance.

Andy Goldsworthy, Storm King Wall (1997–98)

Andy Goldsworthy, Storm King Wall (1997–98). © Andy Goldsworthy. Courtesy of Galerie Lelong & Co., New York. Photo: Jerry L. Thompson. Courtesy of Storm King Art Center.

The environmental sculptor Andy Goldsworthy spent two weeks traversing Storm King’s grounds in search of inspiration for his site-specific commission, according to Stern. Eventually he came upon the remnants of 19th-century farm walls and conceived of a mammoth stone-wall sculpture to sit on top of it, sharply snaking through the woods to suggest that nature cannot be confined to straight lines. It was built over three years by a team of British wallers using traditional masonry techniques to fit together more than 1,500 tons of fieldstone without mortar or concrete.

Goldsworthy originally imagined the wall to be 750 feet long, but he extended it twice so that it snakes all the way to the edge of a pond and up the other side, appearing to resurface from the water. Totaling more than 2,000 feet, it is the artist’s largest single installation and one of Storm King’s most enduring landmarks.

Maya Lin, Storm King Wavefield (2007–08)

Maya Lin, Storm King Wavefield (2007–2008). © Maya Lin Studio. Courtesy of Pace Gallery. Photo: Jerry L. Thompson. Courtesy of Storm King Art Center.

Here’s a fun fact about Maya Lin’s popular earth work for Storm King. “She initially presented one idea to us—a great idea!” said Stern. “But some time later she came back with something new: Wavefield.” They were smart to wait; Lin’s new and improved idea has been a blockbuster with its undulating mounds of earth, some as high as 15 feet, spanning an 11-acre stretch of land. The artist wanted to symbolize the unrelenting force of ocean waves in the context of a living, growing work of land art.

What’s more, she selected the site as an environmental reclamation project, transforming a gravel pit into a sustainable work with low-impact grasses and a natural drainage system. Like Lin’s famous Vietnam Veterans Memorial in D.C., a monument sliced into the earth, Wavefield immerses viewers in a visceral understanding of the natural landscape.

Sarah Sze, Fallen Sky (2021)

Sarah Sze, Fallen Sky (2021). Storm King Art Center, Mountainville, NY. © Sarah Sze. Photo: Nicholas Knight. Courtesy of Sarah Sze Studio.

After Wavefield, more than a decade passed before Storm King’s next permanent commission. Then, seeming to tumble from the heavens came Fallen Sky by Sarah Sze, who formerly represented the U.S. at the Venice Biennale.

The artist created a circular work 36 feet in diameter, made up of 132 individual stainless steel elements pressed into the earth. “The surface of the steel is mirrored, and so what is seen within Fallen Sky is the reflected—and ever-changing—image of the sky above,” said Lawrence. The sculpture’s large scale and shimmering surface allow it to be seen both up close and from far away across Storm King’s rolling fields. Sze’s message is one of never-ending flux, where deterioration and rebirth are in constant rotation as all things have a life cycle—even objects that look like they’ve landed from outer space.

Martin Puryear, Lookout (2023)

Martin Puryear, Lookout (2023). Storm King Art Center, Mountainville, NY. © Martin Puryear. Courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Jeffrey Jenkins. Courtesy of Storm King Art Center.

Lawrence cites Martin Puryear’s Lookout as one of the more challenging sculptures she’s worked on at Storm King. Puryear’s first-ever brick sculpture has an arched opening for visitors to enter at one side, curving upward to a 20-foot-tall dome on the other. “Typically, bricks are used to create structures with strict horizontal and vertical lines, but these are laid in such a way that they end up cantilevering out toward the back of the sculpture—a feat of engineering created with more than 18,000 bricks,” Lawrence said.

The artist was inspired by his research into traditional masonry, including Nubian vault-building that he saw in Mali and the bottle-shaped kilns of ceramics factories in Stoke-on-Trent, England.

Puryear dotted the work with 90 small round windows, or portholes, in order to view the landscape from inside. They also came in handy during the recent solar eclipse. “The smallest of these holes,” said Lawrence, “acted as pinhole cameras, projecting crescent moons onto the brick surface.”