Braided hair, balloons, knobby knees, and nail polish. Emerging artist Dylan Rose Rheingold’s mixed media paintings contemplate girlhood and memory in American culture and its many mementos. The New York-based artist (b. 1997) is known for her scrawling, energetic figurative compositions—made with acrylic, oils, crayons, paper, even highlighter–and which often have the intimately private feel of doodles in a school notebook. “Best in Show”—the artist’s debut solo exhibition at Los Angeles’ M+B (on view through November 18)—opened recently, bringing together new large-scale paintings that explore the suburban phenomenon of high school “color wars”—a school-led competition that splits students into competing “color” teams—in the case of this show, Red vs. Blue.

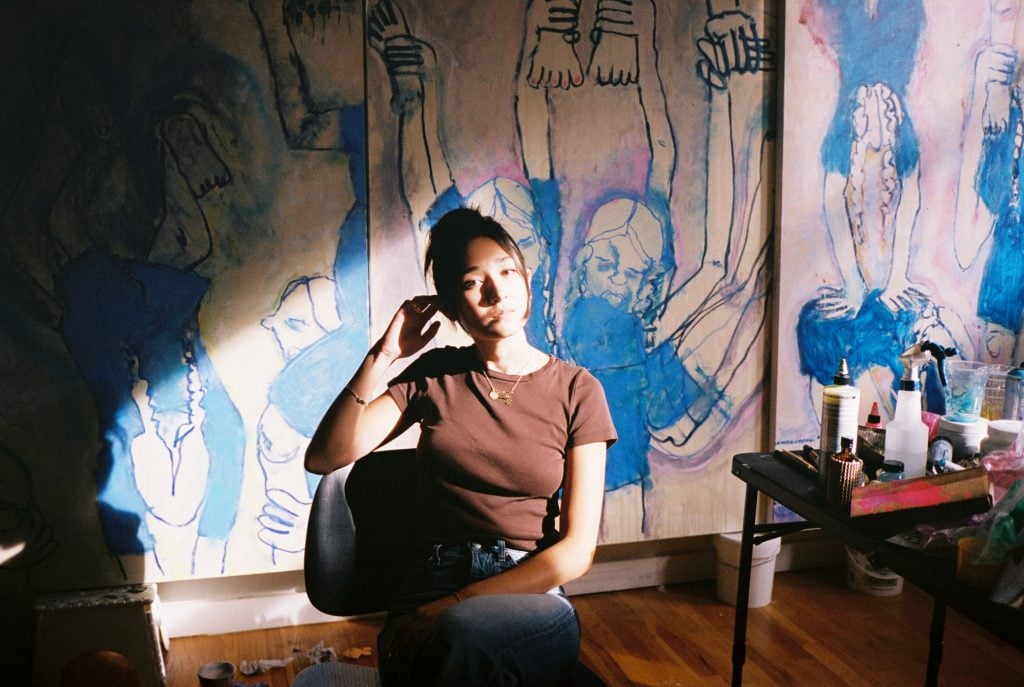

Dylan Rose Rheingold, 2023. Photo: Ellen Lee.

Rheingold’s paintings portray two opposing tumbling teams composed of nearly identical teenage girls in hues of blue or reddish pink. These girls’ changing bodies engage in elaborate tangles of limbs, creating towering pyramids, which later collapse into furious, almost cartoonish piles. These acrobatic entanglements can feel intimate and awkward in some works, and boorishly violent in others. The artist, who earned her M.F.A. from the School of Visual Arts, New York, brings together influence from Philip Guston, Katherine Bradford, and Matthew Barney in these new works.

In the lead-up to the exhibition, we touched base with Rheingold at her Manhattan studio to talk about her own teenage experiences in suburban Long Island, her nostalgia for the early 2000s, and how she spends her studio days.

Installation view of “Dylan Rose Rheingold: Best in Show,” 2023. Courtesy of M+B, Los Angeles.

You’ve just opened “Best in Show”—a debut solo exhibition with M+B in Los Angeles. Can you tell us about the inspirations behind the show?

I had the idea for this project a long time ago. I started the first piece for this show last September. The works are about high school “color wars.” I went to public school in Long Island [New York] where these were popular, the classes would split between teams of “red and blue.” It was a three-to-four-month project that we worked on every day after school. There were all different elements—sports, theater, gymnastics. In my paintings for “Best in Show” I focus on the tumbling aspect. I was never involved in tumbling, but it was intriguing as a spectacle. As I got older, the different rates of development became more pronounced to me—at my school, only girls participated in “red and blue.” Looking back, it’s a very turbulent time when everyone is changing physically and mentally at such different rates. These paintings of tumbling competitions became a way of showing this coming-of-age period that was playful and where I could exaggerate the physical form of these girls and how they interact with each other. In these works there is a lot of togetherness—these girls are physically creating these pyramids or hierarchies. These formations were a way for me to think about value systems and popularity. The gallery is this square space that I wanted to feel like a high school gymnasium. The show opens with paintings of these large-scale physical pyramids and then follows through to their deconstruction, which resembles a dog pile.

Dylan Rose Rheingold, 2023. Photo: Ellen Lee.

How do you see these paintings of tumbling teenage girls as relating to your larger practice and the questions surrounding girlhood that you often explore? How do they expand upon it?

My practice stems from very mundane, banal moments in our day-to-day lives. I’m typically more focused on domestic spaces. Most of my work since my thesis has been a lot more centered on private spaces, and a bit more intimate. This was my first time moving to a public space and making a series that was all within one specific moment. My work can be non-linear and here I wanted to be clear that all these scenes are supposed to be happening in one event.

What’s your studio practice like? Do you make sketches before you start a painting?

For a bit of context, I got my BFA in illustration. I went in for painting and I ended up transferring to the illustration program just because the studio art program was a bit more open-ended and conceptual, and I felt that I didn’t have basic foundational skills. Illustration was really hard—all technique and figure drawing. And at the time it drove me kind of insane because I had to master all these traditional skills. I’m grateful for it now. I think because of that I naturally really enjoy drawing and that’s the root of my process. I’ll start with lots of sketches and once I start to go on a larger scale and start working on wood or canvas, I keep things very loose and intuitive. I don’t like to have much of an underpainting. I’ll make many drawings or studies beforehand but sometimes they don’t work out that way. All the work is mixed media, but I start off with acrylic, just a foundation, and then I start layering it with oil and oil sticks.

Dylan Rose Rheingold, 2023. Photo: Ellen Lee.

How do you know when a painting is done?

I always have a few works going at once. My goal is not to overwork. In the past, I had it in my that I had to push things and check off certain boxes for the work to be finished. It took me a long time to realize that I need to just go with my gut and work in a way that makes me satisfied. I’m not trying to prove anything. Sometimes when you work in a style that’s more abstract it’s easy to get in your head and think maybe something good enough. None of that really matters and once that clicked with me. I need to know for myself if the work is done. Because of that, the paintings do take a long time because my process involves reflecting, critiquing, waiting, and layering on top of that. It’s an internal instinct. Whenever I feel like I’ve gone too far, I’ll layer the base or foundation color back on top and we’ll start again.

What do you do if you feel stuck in the studio?

Sometimes I’ll turn the canvas around. Sometimes I’m just looking at drives me a little bit crazy. I’ll just start working on or continue working on another piece.

I know you’ve mentioned that photography and family photo albums have influenced your work. Can you talk about that?

During the pandemic, I started compiling a family archive of photographs from a little bit of boredom and curiosity. These really helped me find my voice. My mom is from Okinawa, Japan, and she grew up there and in the States at a couple of different military bases. My grandpa was a marine general. My dad is a real New Yorker, a fourth-generation Brooklyn Jewish guy. I had family members send emails and physical books and I started making these collages. After a while, I realized through the images I was pulling and placing together I was interested in the dialogue around contrast and just how culturally, the environment, of both sides of my family, are very different. This idea of otherness was really inspiring and is at the core of my practice. It’s become a lens for my own identity and experiences and that’s more focused on girlhood or selfhood and within American contemporary culture with references to 1990s, early 2000s culture.

Dylan Rose Rheingold, 2023. Photo: Ellen Lee.

How do your materials reference this sense of nostalgia?

I make a lot of my own paint. I use pigments that are very high quality, but then I’ll also mix in other materials. In these paintings for “Best in Show” the girls have clear glitter polish on their nails, nail polish. Other times I’ll include crayon or neon highlighter. Some of these paintings have balloons in them and for those, I incorporated this iridescent paint. In person, from one angle, the painting can look completely flat, but once there’s light paintings glimmer, and the balloons look just like the foil balloons from CVS.

Dylan Rose Rheingold, 2023. Photo: Ellen Lee.

How do you think performance and girlhood interact in this series?

I think being a young woman specifically, you can feel this need to perform at times and without even realizing it. Sometimes young women are put on a platform and kind of forced to react or perform in one way or another. Entering the space I want the viewers, without even knowing it, to feel like a judge and spectator. Here all the girls are mimicking one another. They’re all in uniform even though it fits them all differently. They all have the same French braids. You wouldn’t necessarily pick one as a main character because they’re all assimilating.

There is a darker aspect to high school too. I just want to be honest, even as someone who identifies as a feminist, that there are so many girls who can be so terrible. I want that to kind of be clear within the work. There are lots of parallels to be drawn between these ridiculous social situations like a color war and bullying or judgment. I’m 26 now and I still feel as though I’m able to kind of draw connections to these small moments, When you’re young, a lot of things are pushed to the side and don’t seem to matter, but they really do affect you and follow you throughout life. I grew up in a town that was mostly Irish Catholic and even though I was never bullied, I would definitely shy away from things that made me who I am. It was more that I was subconsciously assimilating. It’s interesting to look back on just those little elements of not being able to fit in a specific box.

Now that the show is up, what are you going to be working on next?

I just got a bunch of huge stretcher bars. My next project will be nicely mindless. I’m going to start stretching the new canvases and then work on some automatic drawings. I am putting big paper up all throughout the studio on the walls so I can go from there and have a fresh start!