Studio Visit

Why Graffiti Legend Lee Quiñones Is a Draftsman at Heart

His current show, "Quinquagenary," marks 50 years since he painted his first subway car.

“I’ve always found myself having to defend my past by not getting trapped by it,” Lee Quiñones told me. “People always want to put you in that box of nostalgia.”

We’re standing in front of his new paintings at his cozy Brooklyn studio on a grey April morning. The works are incomplete for now, merely “atmospheric backgrounds” of colors and forms, Quiñones explained, on which he will draw, paint, and tag. Once finished, the pieces are bound for his third showing at Charlie James Gallery in Los Angeles, in an exhibition called “Quinquagenary.”

Lee Quiñones’s studio. Photo: Min Chen.

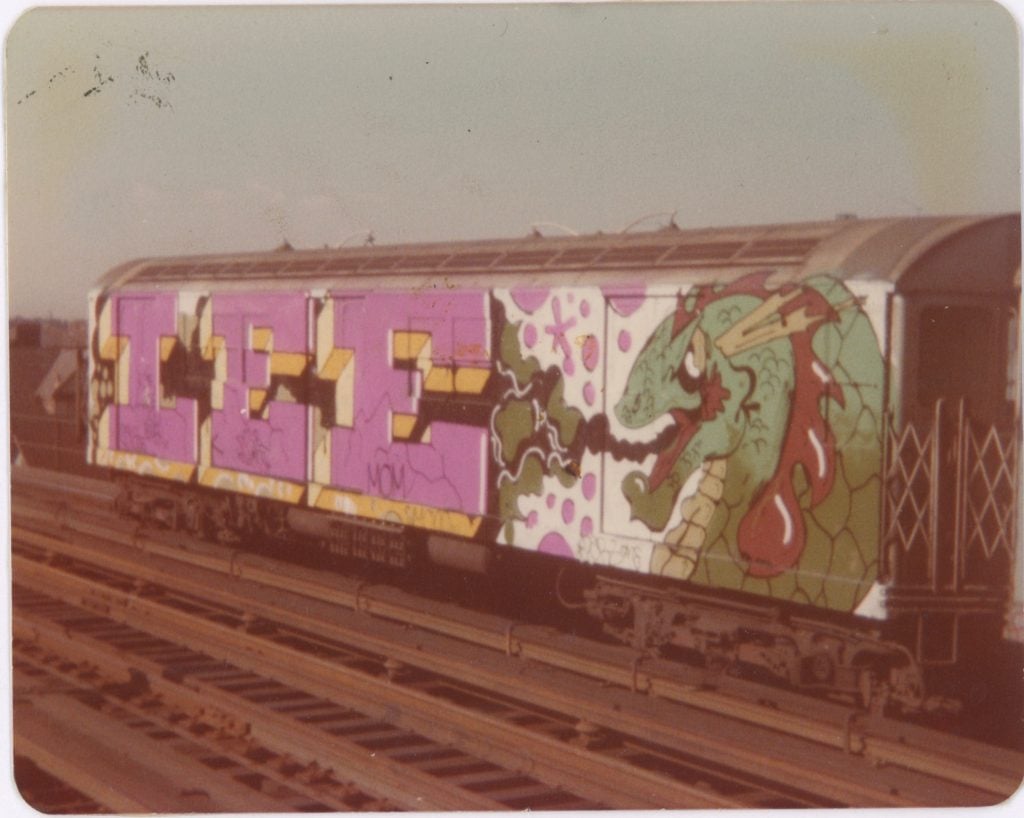

The show’s title nods to the 50th year since Quiñones, who was born in Puerto Rico before moving to New York at a young age, spray painted his first subway car at 14 years old. As one of the city’s earliest graffiti painters, Quiñones would be recognized for his ever-more ambitious (and surprisingly poetic) murals, which set him apart from what he called the “alphabet soup” of tags. He played a role in Wild Style (1983), Charlie Ahearn’s seminal hip-hop film, and in Blondie’s decade-defining video for “Rapture” (1980), which also featured Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Quiñones appreciates the romance and nostalgia attached to the halcyon age of graffiti and street art—but more so, he desires to move beyond it. People still arrive at his studio eager to only see his graffiti work, he said (they leave disappointed). He also brings up Basquiat, a “dear friend,” whose early death sent the prices of his art skyrocketing. “That’s the trapping of that time,” he said. “You have this aura from the era and you’re looking back, but you’re also trying to be, like, ‘Hey, I don’t do that anymore.'”

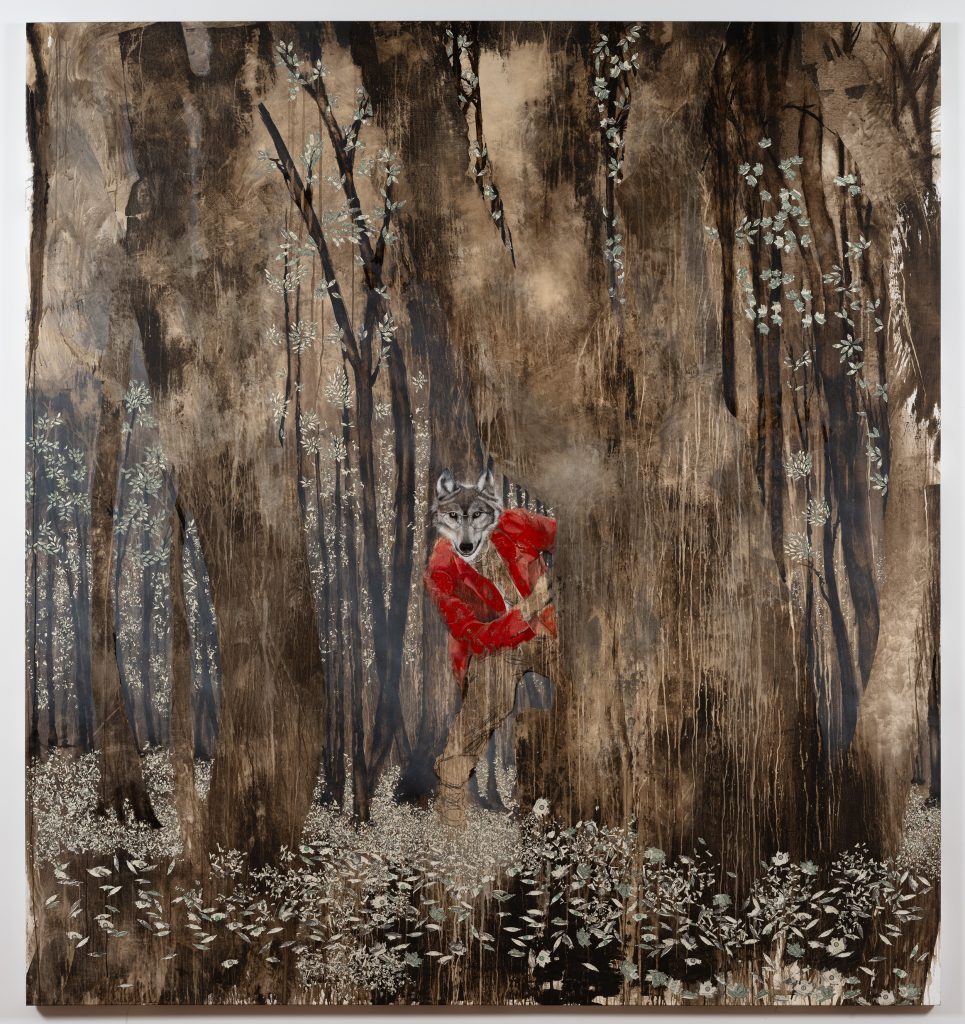

Lee Quiñones, Honest George (2009). Photo: Jason Mandella, courtesy Damiani Books.

Instead, working in the same studio for the past 20 years, Quiñones has matured his creative practice. In a separate unit in the same building, he maintains a showroom, one much more orderly than the “mess hall” where he works. His large canvases are displayed here, textured with a social consciousness, along with smaller works on paper that bear out his delicate draftsmanship. Resting on the floor, his new pieces capture scenes from his past—such as his teenage bedside table and the friend who introduced him to the subway yard—with a voice and confidence earned in the present.

Quiñones’s career milestone is also marked by his first monograph, newly released by Damiani. It traces his creative evolution from his early subway murals through his latter-day artworks, some of which have been collected by the likes of George Lucas, Eric Clapton, and Pérez Art Museum Miami. It’s a good time, then, for a catch-up with the painter to learn how his current studio practice reflects where he’s from and where he’s at.

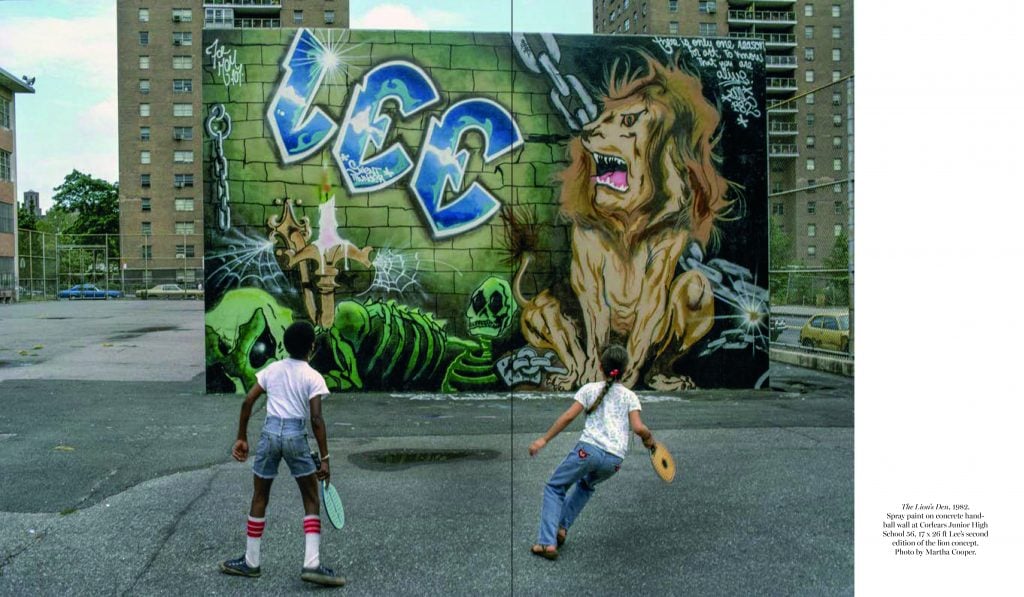

A spread from Lee Quiñones: Fifty Years of New York Graffiti Art and Beyond. Photo courtesy of Damiani Books.

How’s it feel to hold your first artist monograph, to see 50 years’ worth of work compiled in a book?

I used to joke that I don’t have to write a book. I’m in thousands of books; I already have my book out! But yeah, it feels great to have the work documented like this. I was taking pictures of my own trains in 1975 with a little Instamatic manual thing. I knew then at that time that this was something special. I’m like, I’m gonna document this because I can’t even believe I’m doing it. It’s alive and active.

What does it mean to take what you were doing on the street into the studio?

Graffiti is not a thing. It’s an act, it’s a state of mind. I mean, you’re painting on one surface that moves and it’s electrified. Then you’re painting on a surface that won’t move. But here [in the studio], you get more of a chance to critique yourself and be critiqued. So, there’s different levels of stress. When I’m here in the studio, I’m really living and torturing myself with these things. I’m like, Why do I do this? What am I doing?

Lee Quiñones’s workspace with his beloved pencils. Photo: Min Chen.

Sounds like the life of an artist.

It is, it is. When I hear from people who are not artists or sculptors, they don’t know how hot the kitchen gets. Recently, I went to a talk that Mickalene Thomas was giving down in Miami. I love her work and I’ve known her for a while. She went through the whole gauntlet of being a creative person and there were so many things that were so comparable. I told her later I thought I was the only one thinking like that! We could be across the river or ocean from each other and still go through the same process.

What do you do when you get stuck creatively?

I listen to music. I go do something totally different: I’m gonna go clean my car, I’m gonna go talk to some guys about nuts and bolts or something. Then I just feel my way through the darkness and come back. Maybe I have nothing to say at that moment and that’s okay. Should I be here making 30 paintings a week and have a massive amount of work all over the world? Or should it be, you know, Lee’s only got 3,000 works in his whole lifetime? Let them be masterpieces.

Lee Quiñones’s studio. Photo: Min Chen.

Tell me about your studio. What do you love about it?

That every time I walk into the doors, it says, ‘Get your ass in here!’

So, my walls are plastered, but they turn out like this [points to a wall coated with paint streaks and lettering]. It’s a test site. I come up with a title or I hear something in a song and I write it down. Sometimes I have these what I call islands of intellect. One day I can be as dumb as a nail where I can’t remember my own name and I don’t feel like saying anything. The next day, I wake up and boom, it rolls out somehow. It ends up on my walls or in a painting.

A wall in Lee Quiñones’s studio coated with spray paint marks and lettering. Photo: Min Chen.

Do you have a favorite art supply? I’m not going to assume it’s spray paint.

I work with a combination. Every once in a while, I’ll dive into collage. I work with spray paint, mainly European brands. I work with acrylic, and I use a lot of charcoal and pastel pencils. My first love is drawing—just pick up a piece of paper and a pencil, and you’re ready. These are my favorite, Caran d’Ache Super Color pencils.

You do have a shelf of spray paint cans here though. Are they in use or empties?

Some of them are full, some of them are empty. You see this one here? [points to a can labeled Bright Beauty Spray Enamel] I lifted this in 1974. It has been with me 50 years. This was the paint of choice back then. It’s really good paint.

Lee Quiñones’s cabinet of spray paint cans. The one he lifted in 1974 is on the bottom shelf, extreme right. Photo: Min Chen.

Why European brands for your spray paint?

The European cans are the best. In 1979, I was the first one, along with Fab 5 Freddy, to exhibit graffiti-based art in Europe [at Rome’s Galleria La Medusa]. At that time, I was still painting trains in New York so what’s the first thing I do? I go to paint stores and hardware stores—and the color palettes were sick. Here, you would have maybe five or six shades of yellow. There, it was, like, 30 yellows. I’m like, “I’m bringing this shit back to New York!”

But there’s issues with bringing compressed cans of paint [onboard]. I had to carry them on with me, so I didn’t blow the freaking plane. I remember the customs guards, both in Europe and America, going through my duffel bag that’s this big with about 30, 40 cans. They pulled them out and asked, “What is this?” I said, “Art materials—compressed art materials.” And they let me through. Worked for years!

Lee Quiñones, Year of the Dragon (1979). Whole car, top-to-bottom, end-to-end mural on Lexington Avenue IRT Express #5 subway train. Courtesy of artist.

What else do you carry with you from your years painting trains?

I carry self-agency, a purpose, and the ability to express myself. You know, expressing yourself at 14 years old, it may be scattered and all that, but you’re expressing yourself. I knew it was huge. I knew back then. I was like, “Yeah, this is badass.” No one had to tell me that 40 years later. I know and that’s why I kept doing it.

“Quinquagenary” is on view at Charlie James Gallery, 969 Chung King Road, Los Angeles, California, through May 25. Lee Quiñones: Fifty Years of New York Graffiti Art and Beyond is now available from Damiani Books.