Studio Visit

In Her Brixton Studio, Spanish Artist Natalia Gonzalez Martin Puts a Millennial Spin on Medieval Materials of Wood Panel and Rabbit-Skin Glue

We caught up with the artist at her studio as she prepared for several upcoming exhibitions.

We caught up with the artist at her studio as she prepared for several upcoming exhibitions.

Naomi Rea

When I visited Natalia Gonzalez Martin just before Christmas, I recognized some Polvorones, a traditional Spanish holiday cookie, nestled on her shelves alongside a well-thumbed copy of Ovid’s Metamorphosis, and books on Baroque painters and Renaissance masters. It’s a bookshelf you might expect to find in the office of a museum conservator, but a quick scan of the clutter in the rest of the room, haphazardly wrapped paintings, and the remnants of instant ramen noodles in the trash can, situated me in the studio of a young artist.

Born in 1995, Gonzalez Martin creates mesmeric paintings on one of the oldest art forms: wood. At first glance, her delicate wooden panels wouldn’t feel out of place in a Florentine church—but their unsettling female protagonists stare back at the viewer in a way passive depictions from Western art history tend not to. When I visited her studio in Brixton, she was working on a series she said explored “the dark side of self-care,” and the completed paintings were shown at a solo booth at Miart with the Swiss gallery Sebastien Bertrand. Currently, the artist’s works are on view in “Fever of Happiness” as a solo exhibition currently on view at Palazzo Monti, a cultural center and artist residency in Brescia. Her works will also go on view in “Reverie” a three-person exhibition including Ania Hobson and Brittany Miller at Steve Turner Gallery’s pop-up New York space opening June 8.

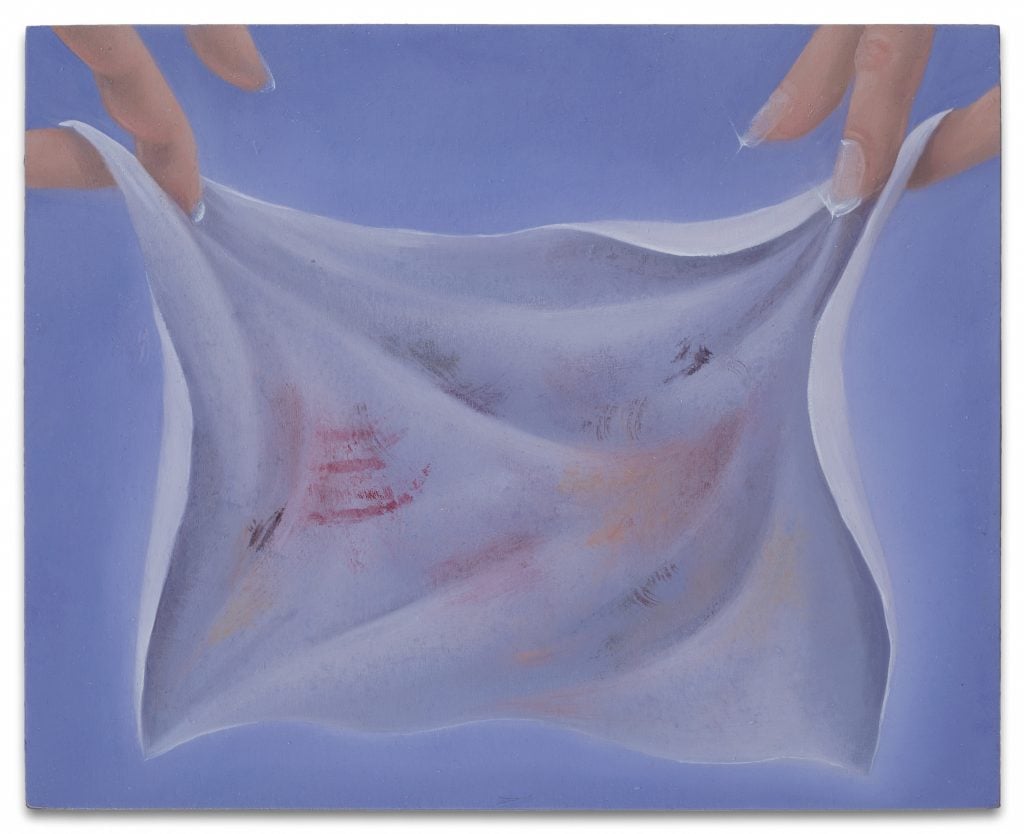

Propped around us on a pair of easels was a suite of soft pastel-colored oil paintings inspired by the painting tradition of “femme a la toilette;” intimate (or slightly voyeuristic) depictions of women grooming themselves in domestic settings. But a closer look at these reclining beauties belies disturbing details. Rather than luxuriating, they appear to be catatonic. One lathers herself in lotion in a striking painting titled The Embalming. Another sits slumped next to what at first appears to be a bowl of fresh berries, or glittering rubies, but on closer inspection looks like a serving of translucent ibuprofen pills. These women are trapped in endless cycles of grooming that never seem to lead to the self-realization or sense of control they were promised.

We caught up with the artist about the artist to talk about her art historical reference points, the perils of working with wood, and summoning divine inspiration in contemporary painting.

Natalia Gonzalez Martin, The Embalming (2023). Courtesy of the artist.

What’s something exciting that has happened for you in the studio recently?

I work from photography, but I have models, and most of the series is portraits of the same model. I’ve only started working with her recently, and this sounds very old school, but I think she’s my muse. Seriously, having this model has opened so many painting doors for me, and I am super excited. Before I used to photograph myself with a timer, but I was getting stuck. I don’t know how to pose, I don’t know how to communicate with my body. Aside from that, I was using stock imagery for body parts. The plasticity of those images comes through sometimes. So I’m really excited to be working with actual models that know what they’re doing.

Do you mix your own colors or do you buy them pre-mixed?

Both. I actually have quite a few pigments that I’ve bought recently, that I’m completely enamored with, that have inspired the colors of the palette. So the purple that you’re seeing here, it’s not exactly the purple straight out of the tube because I always feel like straight off the tube it’s a bit too bright, and sometimes that can be a bit overpowering for the rest of the image. So it’s usually a bit mixed. Sometimes I do use a lot of washes, so it’s paint straight from the tube but so diluted that it loses the color so it becomes almost like another tone in contrast with whatever was below.

And what kind of paints do you use?

It’s always oil paint. I’ve graduated to using a lot of Michael Harding, and it makes a difference. It really is worth it. Like obviously if you’re a student, I don’t recommend it, because all your money goes on it. But if you add a couple of pigments one tube goes a really long way. And also as I’m painting on wood, I am a bit scared of introducing certain other, maybe cheaper, oil paints that might work great for other mediums. Wood is not very forgiving, so you want the best quality pigment. You see everything much more, which can be a bit of an issue.

You’ve got loads of different kinds of brushes here. Which is your favorite?

Just these cheap ones from Jackson’s. They are very used but it’s because they’re really the best—Sterling Pro Arte brushes. I love them because they’re very flexible, but they’re also very stiff. They’re good for blending, and they’re really good for precise, flat lines. And I have not been able to find another brush that does this.

Natalia Gonzalez Martin in the studio. Photo by Naomi Rea.

How does painting on wood compare to painting on canvas, conservation-wise? What do you have to think about during the creation process? Is there anything you’ve learned from art history and how icons or old masters have aged?

I’m not the biggest expert, but when I go to museums, some of the most beautiful pieces I see are always on wood. And they’re the oldest as well. Look at work from the early Gothic period, it was wood, and they still look pretty good! So in my head, unless the quality of the wood has changed, which might be possible, and they were using much superior wood, I’m hoping it will just last.

But there is much more process with wood than with canvas. Well, actually that’s a lie because canvas involves the whole stretching thing, which is probably one of the reasons why I started working with wood secretly. But with wood, you have to prime it a lot more. I’ve tried artificial primers and they really don’t work. They create a film that doesn’t actually adhere to the wood that much, or that’s how I’ve experienced it. So I’ve had to use rabbit skin glue, which is a bit gross to use sometimes. It’s basically like a gel. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen it before. It’s all gloopy like PVA, and it’s not vegan-friendly. If it’s very hot and I’ve applied it, flies come to the studio to eat.

Natalia Gonzalez Martin in the studio. Photo by Naomi Rea.

Let’s talk about your artistic influences. Where does it start, with these old icon paintings on wood?

It starts everywhere because you cannot really pick what came first. I don’t actually know if this is because I’m doing wood or whether I’m doing wood because of this. Nowadays, if I go to a museum, those first rooms with the altarpieces and the triptychs are the main areas where I will stay. I don’t know if this is a bit obsessive but those paintings looks like magic. In any other painting, you can look at it and you can maybe understand how it’s done. But those ones I really cannot figure out. It’s too sleek, it’s too flat. It’s almost digital in a way. And just taking into account the tools they had at that period—it just feels like magic.

And what are your favorite museums to visit?

I have to say El Prado because what type of Spanish person I would be if I didn’t? But it truly is amazing. Recently they restored The Annunciation by Fra Angelico, there are videos of the restoration, and they give you goosebumps, like: ‘Oh my God. Someone has got their hands on that painting!’ And the result is spectacular.

The National Gallery has some really good medieval stuff, and I really enjoyed going to the Getty Museum in L.A. in February. They also have a really good collection, which is weird to see that in America because it’s like European medieval, and the architecture is so modern, it is such a big contrast that makes you appreciate the piece more. I feel like sometimes you can go to a church, which is normally where the most amazing frescoes and altarpieces can be, we don’t see the technicality of it because everything is so technical around it that it doesn’t stand out. But if you put it on a white wall suddenly you’re like, “Shit, this is painting. This is not just interior design.’” And it really changes the perception.

Natalia Gonzalez Martin, Affectations (2023). Courtesy of the artist.

Tell me about this series.

This whole thing is about self-care—the dark side of self-care. It’s a critique of it. So they will become a bit darker than they are looking at the moment.

The dark side of self-care—what was your starting point for the series?

I recently read Madame Bovary. I know it sounds very highbrow, but all of those French authors from that time, the realists, are just a really fun read. It’s very much like watching something on Netflix. And Madame Bovary is a person who wants to get out of what is going on in her mind; she’s never contented. She probably has chronic depression. I wouldn’t say anxiety, but she obviously has something which at that time couldn’t be diagnosed and I think Flaubert knew that even though he didn’t have the words for it. The description is too good for him not to be aware that she’s not well and not just some woman in need of a man. At some point, she goes into that state of depression. It’s so hard that she has to stay in bed and the doctors tell her not to leave. It’s a bit ambiguous, the length of time. It could be a couple of weeks or months because then everyone is very surprised to see her.

That whole idea that you should stay in bed, stay comfy stay in your room, relax, don’t you dare do anything else… If you’ve read The Yellow Wallpaper, it’s the same concept. And I feel we have a bit of that in the speech style around self-care today. It’s the whole idea that “I’m taking a whole day for myself,” I feel the whole culture of self-care is very isolating. The original term was much more of a protest term but now it’s just become like “Where is your face mask? If you are not doing all of this, you are not helping yourself. So it’s your fault if you are bad.” It has become really toxic, and commercial as well. The palette for these is inspired by the Clinique palette.

Installation view Natalia Gonzalez Martin’s solo booth at Sebastien Bertrand Miart 2023. Courtesy the artist.

So what does self-care mean for you in a positive sense?

Well at the moment it’s about getting out of my own head. I think it changes through time, self-care just means making sure you are doing the thing that is best for you at the moment, which again, doesn’t mean that it’s going to be the same for everyone. So something having an aesthetic to it doesn’t make sense because everyone is going to have different needs. So for me, it’s forcing myself to not be inside, which is the opposite of what these people did, which is to isolate. Go out and don’t stay alone for too long. Think of other people basically. It’s not just you here. This whole thing of staying in bed all day, everyone has indulged in it, and it just can sometimes make you feel even worse.

Do you ever get stuck in the studio and not knowing where to go?

Oh, like 90 percent of the time. It’s only very rarely when I’m like, I know exactly what I’m doing with this brush today. Normally it’s just trial and error and very frustrating. But I don’t think that’s ever going to change and I don’t think that changes for anyone. I don’t know many artists who are like: ‘Okay. I know exactly what I’m doing.’ You have to get stuck. It’s horrible but you need to get the thrill when you get unstuck, and then you’re on the biggest high.

How do you get unstuck?

I paint, which is probably not what I should do. I should either be drawing or like, maybe focusing on the research or again, going out and looking. I just sit here when instead I could have spent the day seeing galleries but I feel like if I’m in the studio, this is what I need to be doing. So it’s a bit like, this is why I’m telling myself: don’t do this. Go and see some art, which is the best thing to open up a bit. But I just paint. It means I have a million disgusting paintings that I hope they never see the light of day because they’re proper essays, like: bad.

The thing is again that sometimes you get hit by divine inspiration or something. And it becomes very straightforward. Sometimes you do know actually what you’re doing in the studio. And so this, all of these, I started last week. So they are a week old, they’re babies basically. The things that are put down, I knew exactly what I was doing—it’s the rest that I would probably take a couple of weeks with. Like getting the details of this fabric. I know it’s going to be a lot of work.