Studio Visit

Tasneem Sarkez Is Turning ‘Arab Kitsch’ Into a Bold Exploration of Identity

The Libyan-American artist finds humor in aspects of Arab culture.

The Libyan-American artist finds humor in aspects of Arab culture.

Adam Schrader

Taped to the wall of Tasneem Sarkez’s studio are memes and found items addressing the cultural dynamics of the Arab world. Some of them have serious political undertones, like an image of the character of Calvin from the Calvin and Hobbes series urinating on the head of the former Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi. Others poke fun at modesty gloves for Arab women sold at some New York bodegas.

The 22-year-old artist, freshly graduated from New York University, garnered attention for what she calls her “Arab kitsch” aesthetic well before moving from campus to a private studio in Brooklyn in June. Last year, the library of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York acquired her 2022 book Ayonha, printed using the risograph process.

Sarkez was born in 2002, less than a year after the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, to parents who immigrated from Libya to Portland, Oregon, in the 1970s. As a member of Gen Z, her work expands on the anti-colonial focus of older artists and the concerns of millennials who first harnessed social media around the 2011 Arab Spring protests.

The young artist is represented by London’s Rose Easton Gallery, where she has previously exhibited her work in group shows, and is currently preparing for her first solo show in January 2025. That will be followed by a second show next year at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania gallery Romance.

On her walls, Tasneem Sarkez has included political memes that have inspired her work, including an image of the character Calvin urinating on the head of Muammar Gaddafi. Photo: Adam Schrader.

How do you view your contributions and early rise? What goals do you have next?

I’ve thought a lot about this since I entered the art world in the way that I did, starting younger than I thought I would expect for myself. But the book I did with Endless Editions, Ayonha, has a lot of images, collages and photographs translated to risographs and it is put together in a way that’s intentionally youthful and innocent. There are images of my family and memes I am into because the book was meant to revisit my identity from when I was around the age of 10, but at the age of 21. I was a little overwhelmed and so confused when the Met picked it up for their special collection.

Something about the permanence of that book, living forever beyond me when I am dead—I didn’t sleep that night. It was a chance to hit the ground running. Up until that point, I had been doing art school, art shows, studio visits, and whatever. But the acquisition by the Met was an affirmation, validating the merit of what I am interested in with my work in presenting and archiving Arab modernity as I see it.

But I also realized there’s a lot more I can do going forward, so that was a reason to stay focused. I can’t just stop now. I was literally like, “What’s supposed to happen after this?”

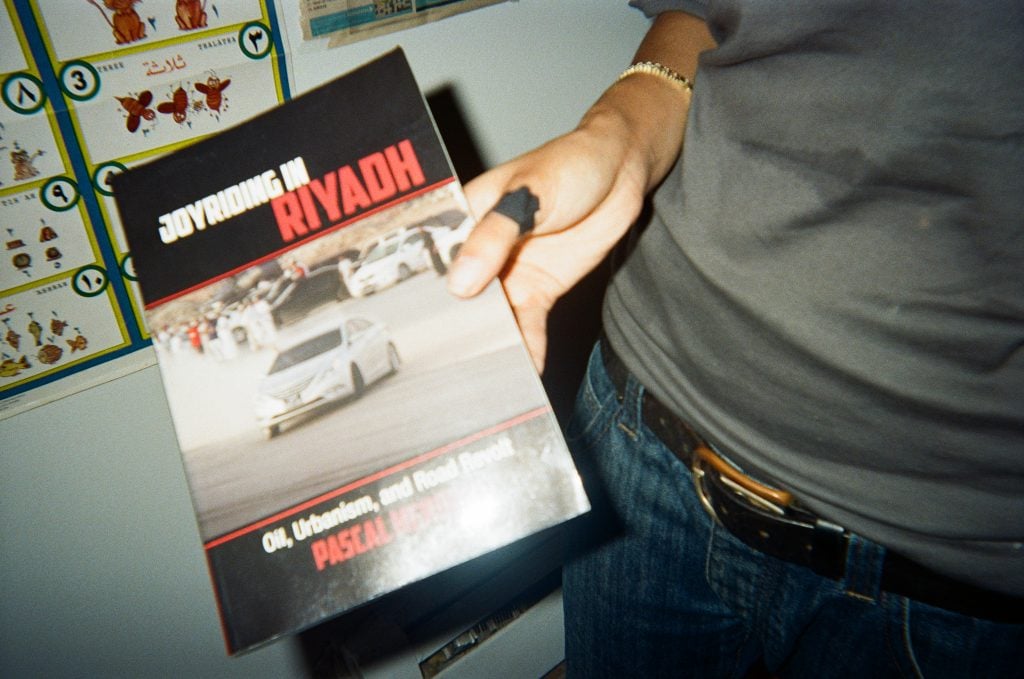

Tasneem Sarkez shows off Pascal Ménoret’s book Joyriding in Riyadh: Joy, Urbanism, and Road Revolt (2014), which has influenced her studio practice. Photo: Adam Schrader.

So how often are you doing things that are project-based like that versus one-off paintings or sculptures?

I do them all at the same time because for me it helps. The sculptures will inform the paintings and such. I also want to produce a book for the show that I’m doing with Rose—but a book that’s more text-heavy, with more of the images that I always talk about that inspire my work.

Can you tell me more about the show coming up? How did it come to be, and what is your goal with it artistically?

Because it’s my first solo show, and the first solo show with Rose, there’s a lot of things that are a marker of our relationship together. But the paintings I have been working on all relate to the intersection of the internet and Arab culture because that really informed my understanding of what it means to be Libyan, what it means to be an Arab woman, more than actual interpersonal conversations with my family—because it’s just a lot.

I think most people can understand it’s just a little easier to navigate that alone, doing your own research into yourself and your history. It’s a lot easier to face that alone. So, I’m looking at the solo show as a collection of all the different patterns of identity that will come through, like roses—my favorite flower.

Tasneem Sarkez shows off a custom perfume bottle with a label reading “White Women Dancing” that will be included in an upcoming exhibition of her work. Photo: Adam Schrader.

You also seem to use cars as a subject for your works. Can you tell me about that?

The car thing came about because I kept seeing these decals and things that felt so specific to me. I just kept thinking about the car as an object—this thing we carry on through the world and choose to adorn. As you’re driving the car, you’re professing the text of that decal to the world.

When I visited Libya, I got to witness this whole culture around cars. [The motorsport of] drifting in the Arab world is so funny but also so serious. It’s all these young guys in their 20s who don’t have anything to do. But ironically their cars, these machines they idolize, are all imported from Western places—and yet they’re wrecking them out of pleasure. Cars reflect so much about the sociopolitical context and places of the world.

But then I like to compose and play with these themes, like when I paired this “I [Heart] Dubai” sticker with this very American nationalistic bald eagle. It prompts the question, who’s driving this car? So, cars become this avenue to understanding my relationship to Arab identity.

Tasneem Sarkez in her home studio in Brooklyn. Photo by Adam Schrader

Is there something about the use of text in the paintings or the depiction of cars that fits with an American audience?

The Americana of it is so ironic as an Arab American born in 2002. We all know what happened in 2001. That event singlehandedly is why my experience growing up is the way that it was and why I’m now revisiting my identity with new eyes to approach my own Arab identity with genuine admiration in a way that was difficult when I was younger.

But yeah, even the depiction of, like, tattoos in my work could feel American. But then I integrate these things that feel more culturally specific because it almost creates this new world for me to be in with my work. When I see all the works I have made in the same room, I can see the potential of where things can go, like playing with language.

Tasneem Sarkes shows off images of modesty gloves that she found humerous and artistically inspirational. Photo by Adam Schrader

A lot of the sculptures I am working on are ready-mades, using things that already exist, so it’s a matter of sourcing and fabrication that I can easily do in my studio. Like, these perfume oil bottles that I’m working on as sculptural works for the upcoming show, I buy them from suppliers on Atlantic Avenue and then I just work on the labeling.

Like, one is called “White Women Dancing.” To give a little context, these shops and stands sell perfume bottles all around Brooklyn that are always dupes of Chanel or whatever. They are already so funny and dyed so specifically with super vibrant and bright colors. But it gets even funnier. These sellers have started giving them ridiculous names. I have a bottle that’s called “Obama.” So, I began to wonder what Obama would smell like, and then made this little game of playing with the words and creating sculptures based on them.

Because it is funny, like humorous, are there any dangers of self-Orientalizing?

In any identity that is marginalized, people will find some way to be offended. I am presenting aspects of Arab culture—but I don’t think my work will be reduced to that because it’s also a reductionist way to approach the work. But I am aware of the boundaries because I know, just from growing up as an Arab American woman, how people will react. It’s just so inherent to me to guard the way I would present myself in certain parts of identity. But with my work I found comfort and freedom to not do that.

I was even nervous when I showed this painting, Good Morning, with Rose in November. It’s a painting of just a red rose. But I was even nervous for that because the text just says “Good morning” but it’s in Arabic. There’s no safety granted in taking pride in Arabness.

Tasneem Sarkez sits on a chair in her studio during an interview. Photo by Adam Schrader

So, what are your thoughts on how these themes and concerns almost end up having to become part of the discussion about the work?

It’s an intention of why I did it in the first place—the language and the people and the way that the text visually has been characterized with almost this violent energy when we see it. A lot of European and American places through the media have really weaponized Arabic text. Part of the decision in wanting to say “Good morning” in Arabic was to show how this very poetic language isn’t granted the worth or respect that English is, for example. But I’m letting the text be there as it is and allowing people to respond on their own terms.