Los Angeles-based dealer Susanne Vielmetter started out with a simple idea for her business: reflect the culture that you see around you. With that in mind, she opened her gallery in 2000 with a diverse, gender-balanced stable of artists at a time when white male conceptual artists were dominating the West Coast scene.

Now, as she marks her 20th anniversary in the business, the world is catching up.

“There is not a single art gallery that would dare show an all white male program,” she says over the phone from her home in Altadena, California.

Vielmetter represents some of the most fascinating artists in the industry, including Nicole Eisenman, Kenyan artist Wangechi Mutu (who recently adorned the Met in New York with her sculptures) and Pope.L, whose career-making Crawl took over Manhattan streets last fall to critical acclaim. She also has a keen eye for emerging talent, like spotting the rising star photographer Paul Mpagi Sepuya.

“I cannot tell you how many times I was told by collectors that they are never going to LA as a point of pride, to prove how cultured they were,” she says with a laugh, recalling the 1990s when LA still had a fledgling art market, despite having a teeming cultural scene.

Today, her gallery is located in downtown Los Angeles in a 24,000-square-foot industrial space. Despite the lockdown, the German expat has been busy. The gallery has been hosting online talks with artists (Vielmetter is often on camera sitting between her tomato plants, her second passion after her gallery), donating to charities monthly, making a web shop to support her art handlers’ artistic practices, and meeting collectors for private walkthroughs while “hanging” virtual exhibitions on the regular. One of her artists, Paul Sepuya, created an editioned work that generated over $200,000 for organizations related to the Black Lives Matter movement.

We spoke with Vielmetter about her gallery, the future of the art industry, and why she thinks exclusivity should not be the art world’s modus operandi during a crisis, or ever.

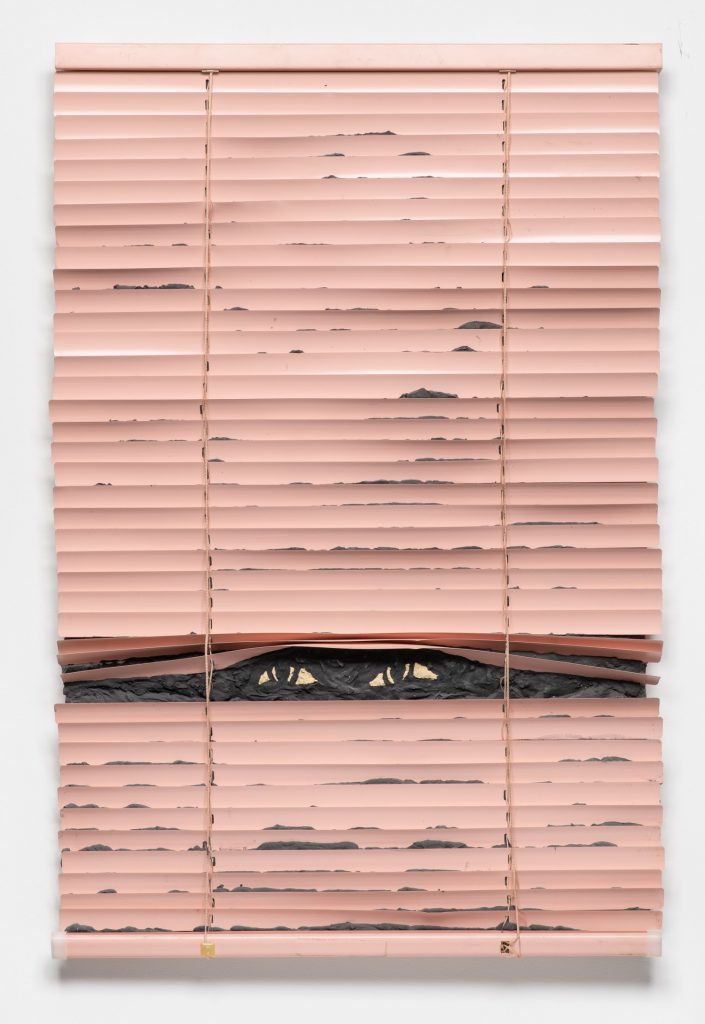

20 year Anniversary Exhibition, 2020. Installation view, Wangechi Mutu, Rodney McMillian. Courtesy of the Artists and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo credit: Robert Wedemeyer.

How has the gallery had to adjust its day-to-day operations during the pandemic?

I’m usually there Fridays and Saturdays for bundles of appointments, but my staff works strictly from home. We made changes so that the preparators can work in separate spaces. Fortunately, I have enough space—that is one good thing about having an enormous gallery right now.

So far, we have only opened the gallery by appointment for people who reach out to me or the directors specifically. We were ready to switch to a more general appointment system, but here in California we are knee deep into another surge in cases. The infection rates are much higher now than they were in March, so we decided that we are not going to make any changes. You have to balance the needs of the business and the safety of staff.

In order to put the gallery on sound footing, we need to assume that we will be in this situation for another year, perhaps even two. I kept almost everybody on my team and we did voluntary salary cuts, but many of those we have actually reinstated. We are preparing to run the gallery on a very slim budget, at least in such a way that we can make it through the next two years.

Obviously, the gallery is not making money but so far we have not lost money. We found that kind of sweet spot where we can keep things in an equilibrium. Whether that is possible to continue, I don’t know that yet. Collectors enjoy the private walkthroughs because they know they are safe when they have the gallery to themselves. At some point, collectors might get sick and tired of continuing to look at art. There is definitely screen fatigue going on. But the gallery has 20 years’ worth of connections and contacts and I have weathered a few crises, and usually those sorts of things come in as a huge benefit.

You have been very active online. How did you find the shift?

If you look at the bigger history of the gallery, we were always on the forefront with digital presence. We had a webpage very early on. We were emailing when it was still seen as a little “cheap.” In April, when I got so scared, my senior director, who is also a programmer, was adamant that we focus on putting content online. I started my garden conversations. We started the initiative for art handlers. We started a web shop. We became more active on our events page. It might not be for everyone, but it helps us stay active and we gained a lot of new collectors and followers this way. We spread out the market. Sometimes we sell a lot of little things, starting as low as $2,000. Nobody is so reluctant to spend small amounts of money, but it adds up. And every time you do that, you create goodwill and you have a conversation.

We feel that the worst thing that can happen is that the gallery becomes silent, because then it becomes invisible. There is a danger of that happening because we are physically not in the gallery anymore. The point is not to narrow our audience right now, we want to widen it. We feel very strongly right now that you cannot narrow your program and make it more exclusive when the going gets tough. Exclusivity is not the thing. You have to go the opposite direction and make everything more inclusive. I know that we are onto something there because I noticed Hauser & Wirth is also doing something with their workers as well.

We are not only in an economic crisis, we are also living through the most profound change that I have ever experienced in my lifetime, one that is long long overdue. All the institutions, including the art galleries, are being questioned right now. There is a huge restructuring of values going on, and we do not know yet where that is leading us. Maybe galleries in the future will not have the same importance anymore. For sure, they will be looked at much more critically. I do think that all of this is necessary, long overdue, and part of a new culture of conversation and changes. My mind says that but, of course, emotionally and physically, it is also hard.

You’re a regular at Art Basel. Since you seem very optimistic about new online models, I wonder if you are also optimistic about the online fair models we have been witnessing since the lockdown this year?

Of course, the fairs are very important to us. Very often artists made specific works for fairs and we paid a lot of money for booths. So far, most of the fairs that we usually do have still happened online. This is quite a big difference to a real fair. We were really lucky with Frieze New York, because we had incidentally planned to show smaller works by two artists and those did really well online.

With Art Basel, I think it was more complicated. In June, the enthusiasm of looking at a fair on a screen had somewhat waned. We did okay. The funny things is that if you subtract the booth costs, the enormous shipping costs, hotel for employees, airfare, then what you have to achieve in terms of sales to break even is only a fraction of what you had to achieve when you had all these costs.

In the bigger picture, it is better for us if we do fairs, we want to do them again and we look forward to doing them again. Realistically, I cannot imagine though that we would do one this year, not with the state of the pandemic in the United States. I am not sure I could convince any of my employees to get on a plane right now. We have to plan without most fairs for a while.

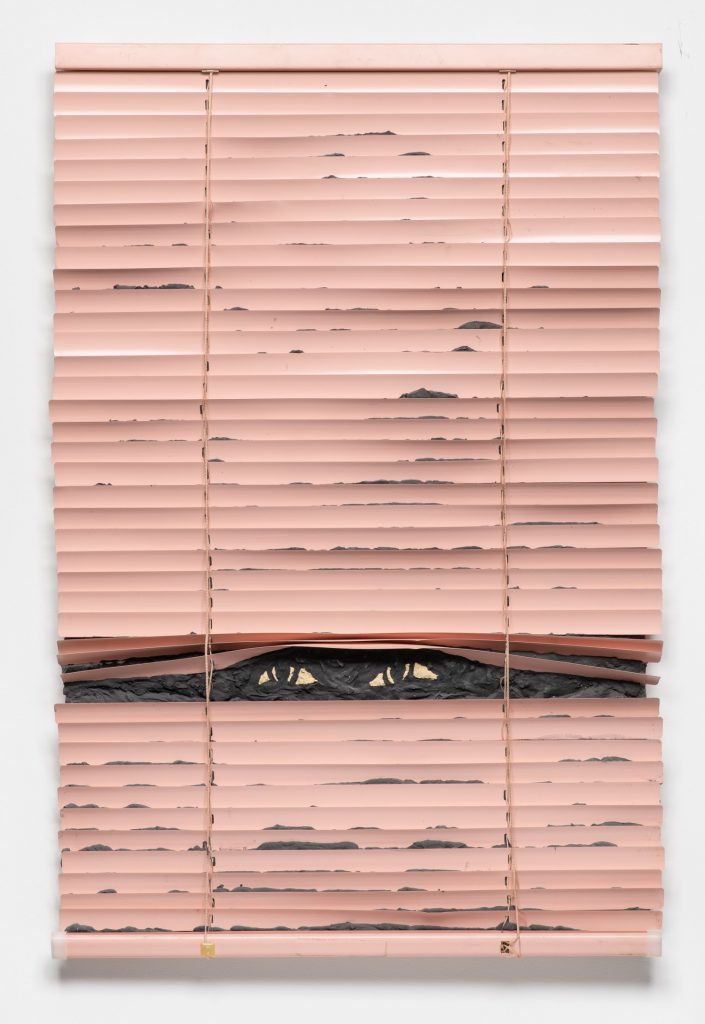

From “The Art of Our Art Handlers” series. Gabriel Slavitt Watching (2017).

You seem to have found impressive alternative solutions. I notice that you are listing prices on your website right now.

In some ways, I am an old-fashioned dealer. I still like to have the price list out on the front desk. My staff laugh at me, but I feel it is a basic tool to do honest business. If you don’t put the prices out there, then who knows them? Sometimes artists are not comfortable with that, and we do not do anything the artists are not comfortable with.

Two days into having our online viewing rooms, I wondered why we were making them private. We are artificially restricting access in a sea of other galleries sending emails about their private viewing rooms. So when we made the viewing rooms available to the public, we decided it was a good idea to also see the prices when possible. The whole idea is that you go in and you look at something and you have all the information there, and then you decide to buy something. Right now, collectors appreciate transparency.

Since you started the gallery, you have been a champion of female and POC artists. It came at a very different time, when the art world was still largely excluding these kinds of artists.

My basic premise for the gallery was always to reflect a cultural reality that is out there, mostly here in Los Angeles, which is a very diverse city. Being an outsider enabled me to see certain things that I thought were very curious and unfair. One of those things was the question of why white men are so overrepresented in these galleries and particularly in LA? The answer was that there were, supposedly, parameters of “quality” as people simply said. “We are just showing the best artists, it’s not our fault that they are all white men.” I did not trust that argument from the beginning. It was too biased and it didn’t have anything to do with what was happening and being talked about in the studios I visited. The biggest challenge was to make that work financially. I had to make many compromises and adjustments. It took many years until I had enough credibility and that collectors would trust me.

How has the art scene in Los Angeles diversified since then?

I cannot tell you how happy I am that we are in an age where there is not a single gallery that does not pay attention to its roster and how it is being perceived. There is not a single art gallery that would dare show an all white male program.

You just moved in Los Angeles last year. What informed the decision to leave Culver City and head downtown?

After 10 years, for me, Culver City had run its course. It is still convenient because it is close to the West Side and we still have a lot of people, but I personally live in Altadena. Travel became a real issue, I was on the road for almost two hours everyday so I was looking for something a bit more centrally located. But also the makeup of Los Angeles is constantly shifting. Most collectors were in Santa Monica, Beverly Hills, and so on in the West. But now, there is a whole new creative class of collectors that has settled in the Silver Lake and Echo Park area, closer to downtown. Downtown has had many attempts at revival, but this most recent one with Hauser & Wirth moving there, seemed like the first time in 30 years that the revival was big enough that I felt that it was there to stay. I hope that the pandemic has not destroyed that.

Speaking of Hauser & Wirth, you share an artist with Hauser & Wirth. How does that work out within the downtown cluster?

We share the artist Nicole Eisenman, who we have worked with since 2007. There is one artist from our program, Charles Gaines, who left almost two years ago. That was the very first time that ever happened to me. I had shown Charles for over 15 years and completely rebuilt the career. But you know [laughs], we have gotten over the breakup. We are friends.

With Nicole Eisenman, Hauser & Wirth approached her and she told me about it. I am totally fine with that. From what I know, her first show is planned for London. I am not sure they would ever show her in LA. The whole question that it needs to be “either/or” between galleries is the wrong question. Both large, mid-sized, and small galleries can offer something to artists that is extremely valuable to them. I feel strongly that most artists would be best served if they weren’t represented by just one gallery. If you are represented by one gallery, you are more vulnerable. Most artists are in a safer position if they have two or three galleries. It is more work to communicate and make sure they are not getting into each other’s hair, but it puts artists on a more sound footing—especially right now.

Yes, that makes me think of Gavin Brown joining Barbara Gladstone and all the artists that did not head over with him. I think that news sent the industry reeling, a sign of what is to come.

Yes, I think that is the beginning of it. If you look at businesses in general, they have been cushioned for months by the government, and that is beginning to run out. If we at least had some kind of timeline right now about when things would get better and when we could reopen. The biggest danger is that a lot of people thought that we could somehow ignore this pandemic, and that the economy would recover. It is clear that the economy will not recover until the pandemic is controlled, and I see no indication of that. Even if I take off my German pessimistic cap, I still see no signs of that.