People

Berlin’s Most Notorious Bouncer on His Day Job as a Photographer, and What It’s Like to Be a Symbol of a Vanishing Club Scene

Sven Marquardt talks about creative life under lockdown and the city's ever-fluctuating club culture.

Sven Marquardt talks about creative life under lockdown and the city's ever-fluctuating club culture.

Kate Brown

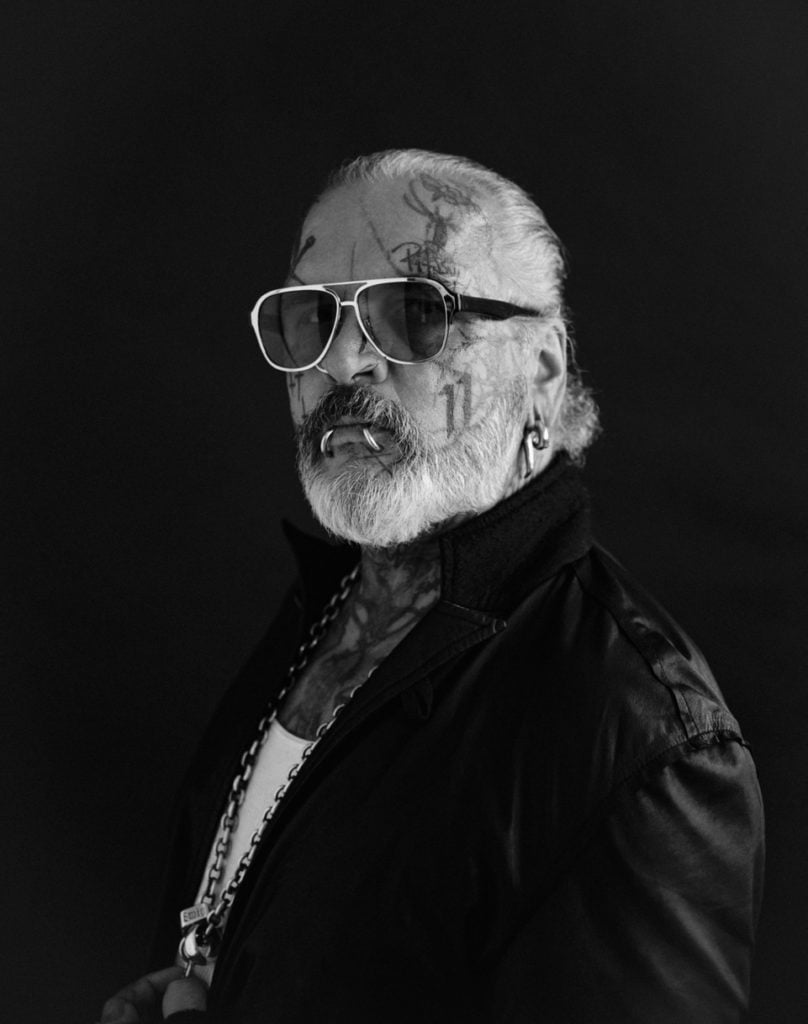

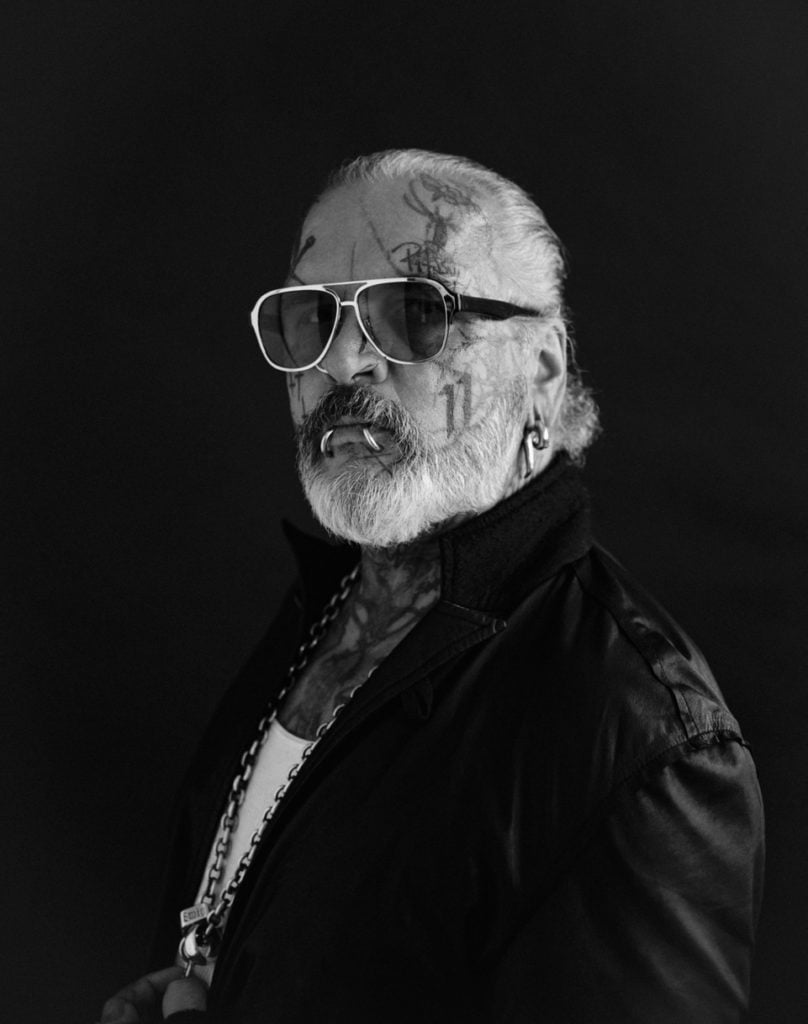

Sven Marquardt is probably the most famous doorman in the world. As the stone-faced gatekeeper of the Berlin nightclub Berghain, he admits or denies the hordes of people who hope to attend the venue’s coveted parties. His criteria for entry is undisclosed, mysterious, and the source of tired speculation. Marquardt is known for glancing over at shivering tourists for a brief moment and, with the slightest shake of his head, sending them off into the night, clueless as to what went wrong.

Marquardt stands on another threshold too: The door is his weekend gig and, by weekday, he is a photographer, a pursuit he picked up in the late 1980s while roaming around East Berlin before the Wall fell. Today, he is represented by Berlin’s DJ label Ostgut—the only artist on its list who is not a DJ. Before the crisis, Marquardt was teaching photography seminars in Florence and Berlin and, last fall, his collaborative installation with German DJ Marcel Dettman, an influential figure in contemporary techno, appeared in a group show at C/O Berlin about the arts and culture of clubs.

More recently too, his own image has started to proliferate widely in memes, appearing as a stand-in for the city’s frustration at the shutdown of clubs, which are in many ways the beating soul of the German capital. Even before the pandemic came crashing down on the city’s nightlife workers in mid-March, important debates were taking place in Berlin about how to better preserve East Germany’s cultural identity, and how to protect club culture from a rush of speculative real-estate developers, the same ones pushing out the city’s artists.

We spoke to Marquardt about his photography, the future of Berlin clubs, and his role as the memetic symbol of Berghain and its carefully preserved mythos.

DJ Hell. Courtesy of Sven Marquardt.

Just weeks before the lockdown took effect, there was a discussion happening in the Berlin parliament about the vulnerability of clubs as independent cultural spaces, which is now compounded by the fact they may not be able to open in 2020 at all. It’s estimated that 100 clubs have closed in the past 10 years in Berlin—and that was before the crisis. How do you see the situation evolving?

Club culture and the situation of clubs in Berlin has always been in flux and a constant state of zeitgeist. As long as there are people who have visions and are brave, there will hopefully always be places like these. The news in the last weeks makes me hopeful that the Berlin senate will help, despite the economic timeout. It gives me the feeling that the city has long understood how important these spaces are.

This is a particularly difficult time for clubs, where the whole point is the free movement of people, porous spaces, strangers in proximity. It’s also a difficult time to be a photographer, especially if you focus on portraiture, as you do. How has the shutdown affected your work at the club, and your studio practice?

Since the early 1990s, club culture has been my foundation and, in that time, there has been at least two generations of change in the scene. Similarly, I have also dedicated myself to new photography projects while a different and younger generation has been presenting itself in the club scene.

Due to international travel for shows and residencies since 2014, as well as my guest lecturing position at Ostkreuzschule in Berlin and POLIMODA in Florence, I have been retreating bit by bit from working the door. I am in my late 50s now, and there are already great young colleagues. But I like to return frequently to the post because the work there is also an inspiration for my photography. However, for the time being, many of my photography projects have to rest, and the club doors are closed. We all hope for a new beginning.

You are a legendary figure in Berlin, a part of the city’s cultural lore. I am curious how you kept busy during the lockdown. Many creatives have found it a good time to get to work and turn inwards.

To me, creativity means a commitment to life and all of its impulses. However, I don’t need a lonely hut near a golden lake and nightclub doors to close in order to finally take the camera in my hand again or to think about new projects. But from the first moment of the pandemic, I saw my situation as not at all detached from world events, so, without panicking, I felt and understood that the situation is very serious and that we must take it seriously.

But would I call it a “good time?” No, I would not subscribe to this kind of mindset under any circumstances. Everyone may process this time differently, but I certainly hope this has been a time for us all to learn a lesson in humility. All of a sudden, nothing is the way it was before.

What do you miss most right now?

What I miss most is going to the airport, preparing for my seminar in Florence, and seeing my Italian friends. I miss driving home through the city in the early morning after a club night. I miss the great guests, DJs, and the energy of the whole house. But Berlin is also now truly home, a place of security, family, and friends. Then again, at the same time, I am homesick for my other world.

Marcel Dettman. Courtesy of Sven Marquardt.

As someone from East Berlin, what were the motivations behind your short film ISOLATION, which came out month. Does the quiet of the streets at all remind you of a time before all the party tourists arrived here, or a freer time before the rampant gentrification of the city? Is it at all a relief to see the streets emptied out?

Berlin was on the way to becoming a metropolis. This lockdown was a hopefully temporary emergency stop for all of us to reflect on that. I had started to film daily recurring rituals in short videos with my iPhone: the ticking of the clock, flowers that fade, candles that burn down, the full moon in the night sky, as well as taking photos. Time documents beauty and decay in a real way, but the situation on Berlin’s streets was surreal at the same time. We are now returning to a bit of normalcy. But the changes in this city will linger with me over the decades.

How do your photography and your work as a doorman inform each other?

Both are interdependent and separate in some ways. The club’s in-house agency Ostgut represents 99 percent DJs and musicians, and then there is me as a photographer. My work as a photographer is of course inspired by club culture and my work at the door, but it is also inspired by my travels abroad and my own photography interests.

Due to Ostgut, many inquiries for my work come from other clubs around the world and, through cooperation with musicians or unconventional presentations, I try to connect art and club culture.

Installation view of “No Photos on the Dance Floor!” Berlin 1989–Today.” Photo: David von Becker.

How has this affected your view on showing in a white cube versus other public spaces?

I love exhibitions in the white cube as much as I love my pictures on house walls, in pedestrian zones, or other public places. Virtual animation and visuals of my pictures are also part of my work since 2016 and connect my analogue process to the digital world.

One of the more talked-about shows last fall was at the photography foundation C/O Berlin. The exhibition, “No Photos on the Dancefloor,” captured the evolution of club culture and included your work. Can you tell me what you thought of the exhibition and what you and DJ Marcel Dettmann presented there?

It was a great success, and I love the catalogue, which summarizes these 25 years of club culture in a wonderful way. As a contributor to the exhibition and protagonist of this scene, my view of the rooms was probably a bit different and more critical than most. It also felt a bit like a local history. And does it really work to exhibit club flyers and brands in glass cases? The Black Box, my project with Marcel Dettmann is actually from 2016. It shows a fictional room that is filled with Dettmann’s sounds and my pictures on four screens. We wanted to leave how the visitors in the room associate and perceive the elements up to each individual.

Installation view from “PACK” by Sven Marquardt. Courtesy Sven Marquardt.

As a photographer you are behind the camera, yet you are a most enduring image of German club culture and Berghain to many people, and very often represented as a symbol of it. Surely you have seen the memes. I wonder what you make of this strange scenario.

My colleagues forwarded me an email one day while I was in Vietnam that said: “Back to the hotel. Marquardt rejected me again.” And there I was, about 14 flying hours away from Berlin. Some things are just the way they are. To be polarizing is not the worst. We don’t work at the club to get be liked or get a lot of likes, but rather for the idea of a place where a lot of people are involved and where there are happy guests.

Let’s talk about the late 1980s and early ’90s. You were an active photographer, and then you stopped after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Why?

For millions of East Germans, the fall of the Berlin Wall meant the partial loss of our own identity. Suddenly, we had a migration background in our country, within a nation. So I put the camera away and went dancing, maybe because the dance floor of the numerous new clubs in East and West Berlin were the first reunited places in the city at that time. I finally got a tattoo, I let myself drift. I did not miss taking pictures at that time and thought maybe working with a camera had just been a phase. The passion had temporarily left me, and then one day it was just there again. I think today that the early 1990s were an equally important time for me, but also for this city, and for this country. Now there is hardly a day that goes by where I am not somehow working on pictures.