On View

In Pictures: See Highlights From the Wildly Ambitious Sydney Biennale, Where Artists Are Reconsidering Our Relationship to Water

The city-sprawling art event is on view through June 13.

The city-sprawling art event is on view through June 13.

Artnet News

If a river could speak, what would it say?

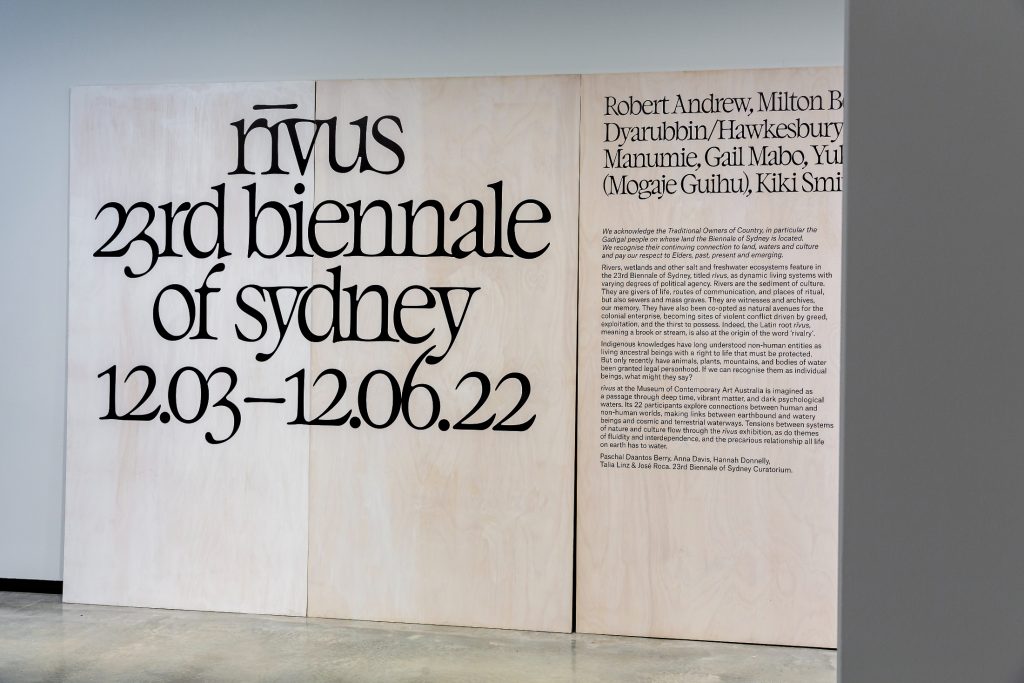

That unusual question is at the heart of the 23rd Biennale of Sydney, on view at six venues across the city through June 13. The sprawling exhibition—called “rīvus,” which means “stream” in Latin—is organized around “a series of conceptual wetlands” in the ancestral lands of the Gadigal, Burramatagal, and Cabrogal peoples. Helmed by artistic director José Roca, it features 330 works by 89 participants.

After years of increasingly dire climate emergencies—droughts and catastrophic flooding, wildfires and deteriorating coastlines—it’s not hard to imagine that if waterways could speak, they would have plenty to say. That’s especially true in Eastern Australia, where devastating floods left two people dead and scores of buildings and artworks damaged earlier this month.

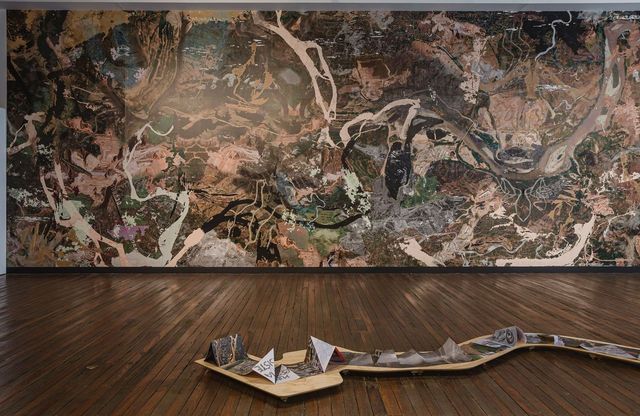

The artists respond in varied ways to the theme of rivers, evoking both the absence of water (in the form of empty water bottles) to its deep connection with storytelling and mythology. At the Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia, Caio Reisewitz’s large-scale collage, MUNDUS SUBTERRANEUS, takes its name from a 17th-century tome written and extensively illustrated by the German scholar Athanasius Kircher, who studied the systems above and below the Earth’s surface. Reisewitz applies Kirchner’s approach to his native Brazil, where deforestation threatens ecosystems, houses are built on stilts to avoid flooding, and politicians are advocating for infrastructure that literally paves over Native lands.

Meanwhile, Manila-based artist Leeroy New created a fantastical sculpture attached to the Information & Cultural Exchange building from recycled plastic water bottles, bamboo, bicycle wheels, and other found objects. The work’s title, Balete, comes from a Southeast Asian tree of the same name, and the sculpture’s undulating form is modeled on the tree’s complex root systems, typically unseen by humans.

Other highlights include the work of artist and activist group Ackroyd & Harvey—Heather Ackroyd and Dan Harvey—who co-founded Culture Declares Emergency in 2019. Through a process they call “photographic photosynthesis,” the duo creates images to call attention to dwindling natural grasses around the world.

See more images from the biennale, organized by venue, below.

Foreground: Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, The Substitute (2019). Background: Cave Urban, Flow (2022) (detail) and Ackroyd & Harvey; Uncle Charles “Chicka” Madden / Wanstead Reserve, Cooks River, Sydney, 2022; Lille Madden / Wanstead Reserve, Cooks River, Sydney (2022). Courtesy the artists. The Cutaway at Barangaroo. Photography: Document Photography.

Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, The Cutaway at Barangaroo. Photography: Document Photography.

Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, The Cutaway at Barangaroo. Photography: Document Photography.

Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, The Cutaway at Barangaroo. Photography: Document Photography.

Badger Bates, Barka The Forgotten River and the desecration of the Menindee Lakes (2021–22); Wiimpatja Paakana Nhaartalana (Me Fishing in the Darling River) (2004); Warrego-Darling Junction, Toorale (2012); Ngatyi Yarilana (Rainbow Serpents having young) (2007); Barka (Darling River) (1992). Courtesy the artist. Art Gallery of New South Wales. Photography: Document Photograph.

Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Art Gallery of New South Wales. Photography: Document Photograph.

Ackroyd & Harvey, Lille Madden / Tar-Ra (Dawes Point), Gadigal land, Sydney (2022).Art Gallery of New South Wales. Photography: Document Photography.

Naziha Mestaoui, One Beat, One Tree (2012). Courtesy the artist’s estate. Art Gallery of New South Wales. Photography: Document Photography.

Caio Reisewitz, MUNDUS SUBTERRANEUS (2022).Courtesy the artist & Bendana Pinel Art Contemporain, Paris.

Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Photography: Document Photography.

Marjetica Potrč, The House of Agreement Between Humans and the Earth (2022); The Time of Humans on the Soča River (2021); The Time on the Lachlan River (2021–22); The Rights of a River (2021); and The Life of the Lachlan River (2021). Courtesy the artist & Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm/Mexico City. Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Photography: Document Photography.

Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Photography: Document Photography.

Yuko Mohri, Moré Moré Tokyo (Leaky Tokyo): Fieldwork, (2009–21).Courtesy the artist & Akio Nagasawa. Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Photography: Document Photography.

Sopolemalama Filipe Tohi, Haukulasi (1995–21). Foreground: Clare Milledge, Imbás: a well at the bottom of the sea (2022) (detail). Courtesy the artist & STATION. Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Pier 2/3 Walsh Bay Arts Precinct. Photography: Document Photography.

Foreground: Julie Gough, p/re-occupied (2022) (detail). Courtesy the artist. Background: Clare Milledge, Imbás: a well at the bottom of the sea, (2022) (detail). Courtesy the artist & STATION. Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Pier 2/3 Walsh Bay Arts Precinct. Photography: Document Photography.

Yuko Mohri, Moré Moré (Leaky): Variations (2022). Courtesy the artist, Project Fulfill Art Space & Mother’s Tank Station Ltd. Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Pier 2/3 Walsh Bay Arts Precinct. Photography: Document Photography.

Left to right: Aluaiy Kaumakan, Semasipu – Remembering Our Intimacies (2021–22). Courtesy the artist, Paridrayan Community elder women, Linkous Kuljeljelje, Chun-Lun Chen & curator Biung Ismahasan; Yoan Capote, Requiem (Plegaria) 2019–21 (detail). Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Pier 2/3 Walsh Bay Arts Precinct. Photography: Document Photography.

Leeroy New, Balete (2022) (detail). Courtesy the artist. Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Arts and Cultural Exhange. Photography:

Document Photography.

Leeroy New, Balete (2022) (detail). Courtesy the artist. Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Arts and Cultural Exhange. Photography: Document Photography.

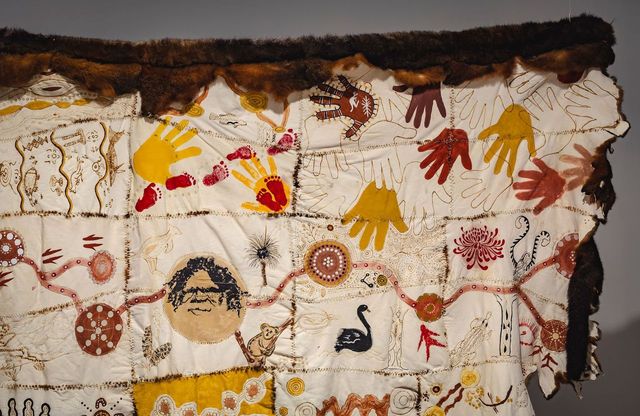

Carol McGregor with Adele Chapman-Burgess, Avril Chapman and the Community of the Myall Creek Gathering Cloak, Myall Creek Gathering Cloak (2018). Courtesy the New England Regional Art Museum & the Myall Creek Gathering Cloak Community.

Wura-Natasha Ogunji, Lagoons and Lagoons and Lagoons (2021) (detail). Courtesy the artist & Fridman Gallery, New York.

Carolina Caycedo, Serpent River Book and Serpent Table (2017) (detail). Background: Yuma, or the Land of Friends, (2021). 2022, National Art School. Photography: Document Photography.

Left to Right: Carolina Caycedo, Elwha (2016) (detail); Watu (2016) (detail); Iguaçu (2016) (detail). Courtesy the artist. National Art School. Photography: Document Photography.