On View

Tomoko Sugimoto, Takashi Murakami’s Painting Director, Takes Time Out for Her Own Gallery Show

Can embroidery set the artist on a path to enlightenment?

Can embroidery set the artist on a path to enlightenment?

Sarah Cascone

Tomoko Sugimoto is currently only working part time—by her standards—at her long-time post as the painting director for Japanese Pop artist Takashi Murakami. It’s a busy job that often has the Brooklyn-based artist traveling the world, but scaling back has allowed her the time to prepare her own solo show, “The Unseen World,” a pop-up exhibition currently on view at New York’s Parasol Projects.

The small group of works was selected by independent curator Zahra Sherzad and features a number of Sugimoto’s delicate embroidered canvases as well as the artist’s first foray into sculpture, which, she told artnet News, took some six months to produce.

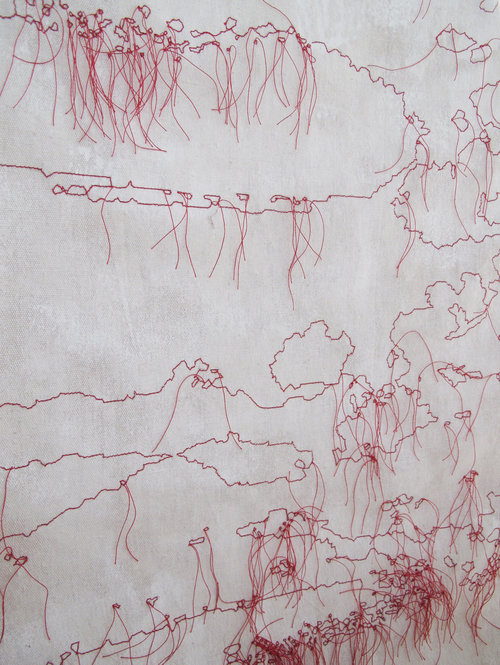

That sculpture is the show’s namesake and centerpiece, a six-foot-tall white tepee embroidered with outlines taken from photographs of atomic bomb clouds. Reduced to simple graphic forms, the clouds at first appear peaceful, but reveal their ominous nature upon a closer look. “It shows the intensity of her work,” said Sherzad. Where the front “is very effortless and serene, when you go to the underbelly of her work, you see the amount of labor and hours that she puts into each piece.”

Tomoko Sugimoto, The Unseen World (detail). Courtesy of Tomoko Sugimoto.

Sugimoto was inspired to move into sculpture because she had found that “people were really interested in the back of my pieces also.” The dense network of hanging threads left behind by her process are clearly visible through the tepee’s opening, and Sugimoto has also pulled the thread back through to the front along the bottom of the piece, subverting the viewer’s expectations for the form.

In the West, embroidery is considered very feminine and domestic, but that’s not necessarily the proper lens through which to view this work. “Maybe in Japan, it’s not feminine,” said Sugimoto, who grew up in Tokyo, noting that men working in the practice were more likely to be in charge of producing embroidered garments.

One of the pieces on view in “Tomoko Sugimoto: The Unseen World.” Courtesy of Tomoko Sugimoto.

She actually adopted the medium as a necessity of her work: With her hectic travel schedule, painting and sculpture just weren’t practical because she couldn’t take them on the road. Sugimoto also felt it might set her work apart. “I thought, ‘No one really does that, drawing with thread,'” she recalled.

Sugimoto began by embroidering figurative scenes, such as children climbing up poles, accenting her work with colored paint. Later work veers toward abstraction, the drawing reduced to simple lines that flatten the image.

Tomoko Sugimoto, The Unseen World (detail). Courtesy of Tomoko Sugimoto.

Sugimoto relies heavily on the color red, which is traditionally auspicious and joyful in Asian cultures. Over time, however, she has come to use the color in different ways. The Unseen World, inspired both by the destruction of World War II and Japan’s more recent 3/11 tragedy, is quite bleak. Its profusion of hanging red threads visually suggest blood raining down from the ominous clouds.

Other work is meant to be more peaceful, such as the many tiny canvases, each between three and seven inches in diameter, that make up The 108 Floating Feelings, a work inspired by the Buddhist quest for enlightenment. Sugimoto’s process for creating these works, sewing around each canvas in a tightly spiraling line, was meditative. Varying the sizes and colors of the individual pieces, Sugimoto intends each element to represent one of the 108 temptations that keep mankind from achieving Nirvana.

Tomoko Sugimoto, The 108 Floating Feelings. Courtesy of Tomoko Sugimoto.

The time-consuming, tedious process of creating such works likely went a long way toward freeing the artist’s mind, but Sugimoto makes it clear that she isn’t there yet. From the center of each canvas hangs a long string, a reminder that the search for enlightenment is a lifelong journey.

“Tomoko Sugimoto: The Unseen World” is on view through September 11, 11:00 a.m.–9:00 p.m., at Parasol Projects, 2 Rivington Street.