Art World

Takashi Murakami’s ‘Jellyfish Eyes’ Is a Balm for Tsunami Trauma

The new live-action movie could be next generation Pokémon.

The new live-action movie could be next generation Pokémon.

Sarah Cascone

Takashi Murakami, Jellyfish Eyes (2012). The children and their F.R.I.E.N.D.s.

Photo: Courtesy Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd.

Takashi Murakami‘s feature film debut, Jellyfish Eyes, which screened Sunday at New York’s Film Society of Lincoln Center, feels at once strikingly original and strangely familiar. That’s because the artist has repackaged elements from Japanese and Western film traditions, drawing on everything from 1950s-era Japanese monster movies such as Godzilla to E.T. and Pokémon, to create his own unique hybrid. The result is essentially a live-action anime film featuring seamlessly integrated CGI elements.

Set after Japan’s devastating 2011 earthquake and tsunami, Jellyfish Eyes tells the story of Masashi, a young boy who moves with his mother to a small Japanese town after his father died during the disaster. Soon, he becomes friends with an adorable jellyfish-like creature. He names the CGI critter Kurage-bo and carries it around in his backpack.

On Masashi’s first day of school, he discovers that all his classmates have similar pets they kept hidden from the grown-ups, called F.R.I.E.N.D.s. Unlike Kurage-bo, these other monsters come with iPhone-like devices that the children use to control them. The boys at school use these monsters to fight each other, unknowingly channeling their aggression and negative energy.

Murakami’s take on the imaginary friend narrative popularized by the likes of Calvin and Hobbes perfectly captures a child’s instinct to retreat into escapist fantasy, especially in times of crisis. The school children may seem cute enough, but their battling F.R.I.E.N.D.s are a physical manifestation of their troubles: Some are orphans, others have overbearing parents, or parents who are completely self-absorbed and absent.

For the most part, Murakami has created fairly original-looking monsters for his F.R.I.E.N.D.s, although Yupi—who belongs to the class bully Tatsuya—with its wide-set eyes and green coloring, resembles a shorter, squatter Rango. When they aren’t fighting, the creatures imbue the film with a sense of childlike wonder and whimsy.

The antagonists are the Black-Cloaked Four, who dress in ominously hooded black cloaks, have classic anime character names like Vermillion Bird and Blue Dragon, and are prone to maniacal laughter. They work at the world’s creepiest lab, more of reclusive hacker’s den than a real science facility, and have given the children the F.R.I.E.N.D.s as part of a scheme to tap into their negative energy and access a supra-universal power.

Takashi Murakami, Jellyfish Eyes (2012). Masashi and Saki.

Photo: courtesy Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd.

In typical anime fashion, Murakami relegates Masashi’s female classmates to background character status, except for a girl named Saki, who becomes his closest non-imaginary friend and ally. Saki hates the F.R.I.E.N.D.s’ fighting, which is understandable, given that the unsupervised episodes of kid-on-kid violence have a dark, Lord of the Flies-like quality.

The battle sequences certainly recall those of Yu-Gi-Oh! (though with less narration) and Pokémon, especially as the children thrust their devices up in the air, almost as if they are releasing their Pokéballs. One of the F.R.I.E.N.D.s, Miss Ko2 (originally a 1996 sculpture by Murakami, based on Sailor Moon), even goes so far as to shout the names of her attack moves, such as “sky dragon lightning!”

Takashi Murakami, Jellyfish Eyes (2012). The children controlling their F.R.I.E.N.D.s with their devices.

Photo: courtesy Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd.

Masashi spends a great deal of the film’s last third grunting and moaning as he struggles to save his friends and defeat the Black-Cloaked Four. Anyone who spent any time watching Cartoon Network’s Toonami programming may find themselves experiencing flashbacks to Goku’s extended power-up sequences on Dragon Ball Z. Murakami also employs that iconic anime convention, the diagonal split-screen of intense emotion, with two boys on either side shouting encouragement to their battling F.R.I.E.N.D. counterparts.

The lurching, oversize F.R.I.E.N.D. Oval, a dark and twisted version of the children’s adorable companions whose summoning sets the stage for the film’s finale, is reminiscent of other distorted, mutated anime villains, such as Tatsuo in Akira or Spirited Away‘s No-Face. Satisfyingly, if predictably, the children and their cute little monsters set their differences and band together to save the town from their common enemy.

Takashi Murakami, Jellyfish Eyes (2012). Masashi and Saki with their F.R.I.E.N.D.s.

Photo: courtesy Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd, and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles.

In the end, Jellyfish Eyes rises above pastiche status as a moving portrayal of childhood struggles against loneliness and bullying. It also coalesces children’s fears of natural disasters and man-made calamities. It is a film that responds to recent events in Japan, such as the earthquake and the Fukushima nuclear disaster, but speaks to universal concerns and themes.

As artnet News reported last month, Jellyfish Eyes is currently on a nine-city US tour, complete with merchandise like stuffed animals, key chains, and apparel based on the lovable F.R.I.E.N.D.s. Murakami’s Los Angeles gallery, Blum & Poe, organized the tour with the artist’s art production company, KaiKai Kiki.

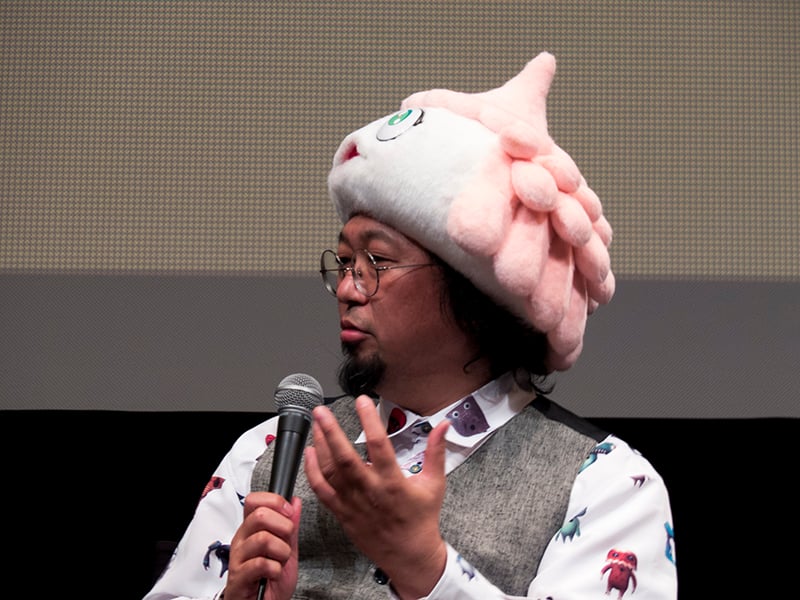

Takashi Murakami at a screening of Jellyfish Eyes at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, wearing a Kurage-bo hat. Photo: John Wildman, courtesy Film Society Lincoln Center

While a crossover video game might seem like a natural fit, Murakami thinks he is too old to play video games. In a post-screening Q&A session on June 1, he said he has no plans for a game adaption, though he’s not opposed to someone else putting it together. That said, he’s far from finished with his cast of F.R.I.E.N.D.s; Jellyfish Eyes 2 is currently in post-production, and a final film to complete the trilogy is planned.

Jellyfish Eyes will next be shown at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum at 6:30 p.m. on June 5. The screening is free with museum admission, which is only $5 after 5:00 p.m. on Thursdays.

Watch the trailer for Jellyfish Eyes: