Art & Exhibitions

Take a Tour of the Berlin Biennale

We checked in with curator Juan Gaitán to get a sneak peak.

We checked in with curator Juan Gaitán to get a sneak peak.

Alexander Forbes

Ahead of the opening of the eighth Berlin Biennale on Wednesday evening, artnet News checked in with curator Juan Gaitán about the main tenets of the three-institution-spanning show and took a sneak peak at some of its highlights.

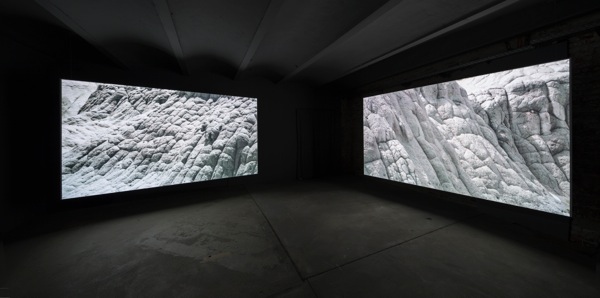

Installation View, Museum Dahlem, Wolfgang Tillmans

Photo: Anders Sune Berg, Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; Maureen Paley, London; David Zwirner, New York

You chose to place much of the Biennale in two of Berlin’s least-central museums, the Haus am Waldsee and the Museum Dahlem. What drove that decision?

I wanted to place a greater focus on the city of Berlin as a whole, and not just Berlin-Mitte, which has in recent years become the cultural center of Berlin, both symbolically and in reality. What I mean by this is that Mitte has in many ways become a stage where the main tourist attractions have been built in the wake of the fall of the Berlin Wall. By placing the Biennale within the Haus am Waldsee and Museum Dahlem, I hope to create a wider perspective that extends beyond the revitalization of the 18th and 19th centuries in present day Mitte [as exemplified by the reconstruction of the Prussian-era palace, the Berliner Schloss on the Humboldt Forum].

Anri Sala, UNRAVEL (2013) at Museum Dahlem

Photo: © Alexander Forbes

The Museum Dahlem is an interesting site for the Biennale, because as the home of Berlin’s non-European and ethnographic collections, visitors come with a different approach to the objects than they typically do when going to look at ‘art.’ The methods of contemporary art follow critical thinking of the Enlightenment and can be said to be colonial, in that they can appear anywhere. In contrast, ethnological objects require specific display methods. It is intriguing to think about how unorthodox methods of display are used differently in both contexts and how the use of that one display device can alter a viewer’s experience with an object or artwork.

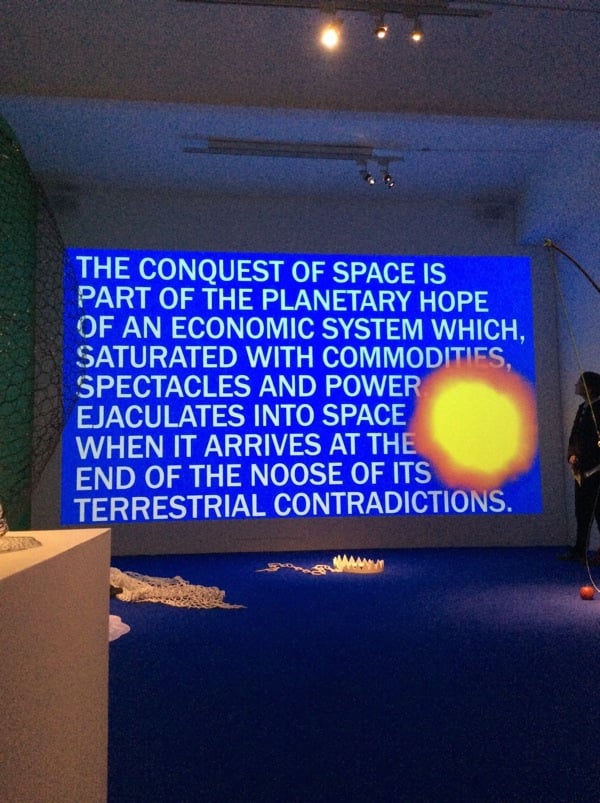

Set for Goshka Macuga‘s Prepatory Notes for a Chicago Comedy (2014) at the Museum Dahlem

Photo: © Alexander Forbes

The Haus am Waldsee is important for the Biennale because is confronts issues of the private and public when engaging with artworks. The site itself was originally built as a private mansion in the 1920s. Its history makes it a symbol of the early 20th century bourgeois romanticism that existed in the Berlin suburbs of Dahlem. Now as a museum in the 21st century, it still maintains a domestic feel and therefore visitors engage with the artworks on a more intimate scale. This inevitably raises questions regarding what art does for the individual in one’s private life.

David Zink Yi, The Strangers (2014)

Photo: Anders Sune Berg, Courtesy David Zink Yi; Hauser & Wirth, London/ New York/Zurich; Johann König, Berlin; Livia Benavides 80M2, Lima

A lot of the Biennale deals with an interrogation of image culture. What’s your specific point of contention?

I am interested in how individuals engage with images on a private and public level. In pre-modern history, images were reserved for religion, as icons to be venerated in both public and private spheres. It was only with the modern invention of the printing press that images were separated from religion. However, non-religious images were originally experienced and consumed publicly. For example, when a newspaper was posted, it was read out loud to an entire congregation.

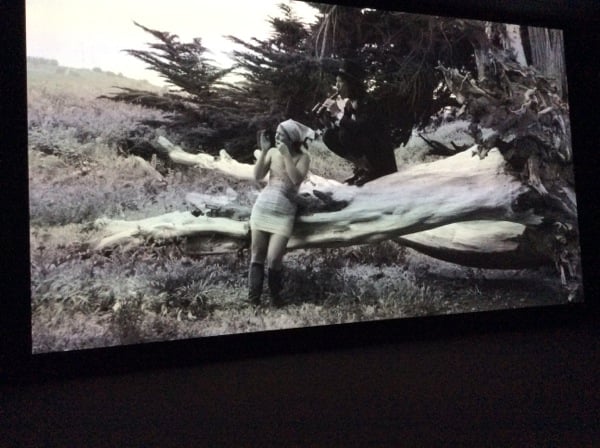

Julieta Aranda, Stealing one’s own corpse (An alternative set of footholds for an ascent into the dark) (2014)

Photo: © Alexander Forbes

When thinking about a viewer’s engagement with images today, I am not only interested in the turn toward a private experience, but also with the relationship between the image and political life. Certain political and social issues are unrepresented by the media and therefore do not exist in public consciousness. Others are hyper-represented and create a public numbness. In either case, both tend to escape political action.

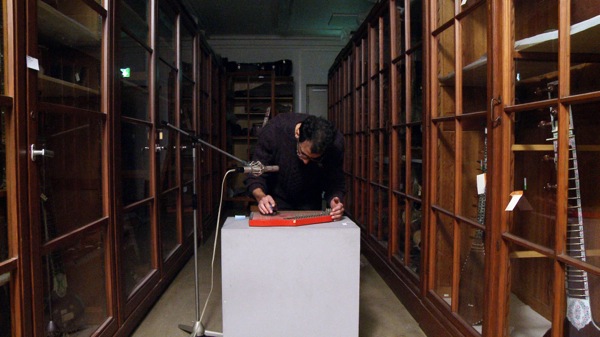

Tarek Atoui, Dahlem Sessions (2013- )

Photo: Marcin Malaszacak

The programming seems much more concentrated than many other recent editions of the biennale. Was that a conscious effort to put the focus back on the exhibition itself rather than its context?

There is a conscious effort to place the focus on the exhibition. My curatorial approach was concerned with the framework, which may be represented by brackets. The space between the brackets is where the works can appear individually as critical propositions.

Leonore Antunes, A secluded and pleasant land. in this land I wish to dwell (2014) at KW

Photo © Alexander Forbes

What was the biggest challenge of curating the biennale?

There were not many big challenges; however, unfortunately the city of Berlin does not belong to long of list of [the biennale’s] supporters.

Carlos Amorales, The Man Who Did All Things Forbidden (2014) at Museum Dahlem

Photo: © Alexander Forbes