Art World

Why You Should Care About Artist Tala Madani

Unknown yet ubiquitous, an LA painter is not afraid of the male ego.

Unknown yet ubiquitous, an LA painter is not afraid of the male ego.

Laura van Straaten

The animator and figurative painter Tala Madani has pulled off an interesting feat this summer, managing to be practically ubiquitous, yet still largely unknown.

The artist, who lives in Los Angeles, had her first solo museum show in the US, “First Light,” debut at the MIT’s List Center in May. That exhibit was organized in conjunction with the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, where a smaller version premiered earlier this year.

Madani spoke by telephone from her home near the Highland Park area of Los Angeles, as her nine-month-old daughter giggled and squawked in the background. The artist was born in Tehran in 1981 and emigrated to the US as a child. Her studio is in the same Lincoln Heights building as that of her husband, Nathaniel Mellors, the sculptor and video artist who will co-represent Finland at next year’s Venice Biennale.

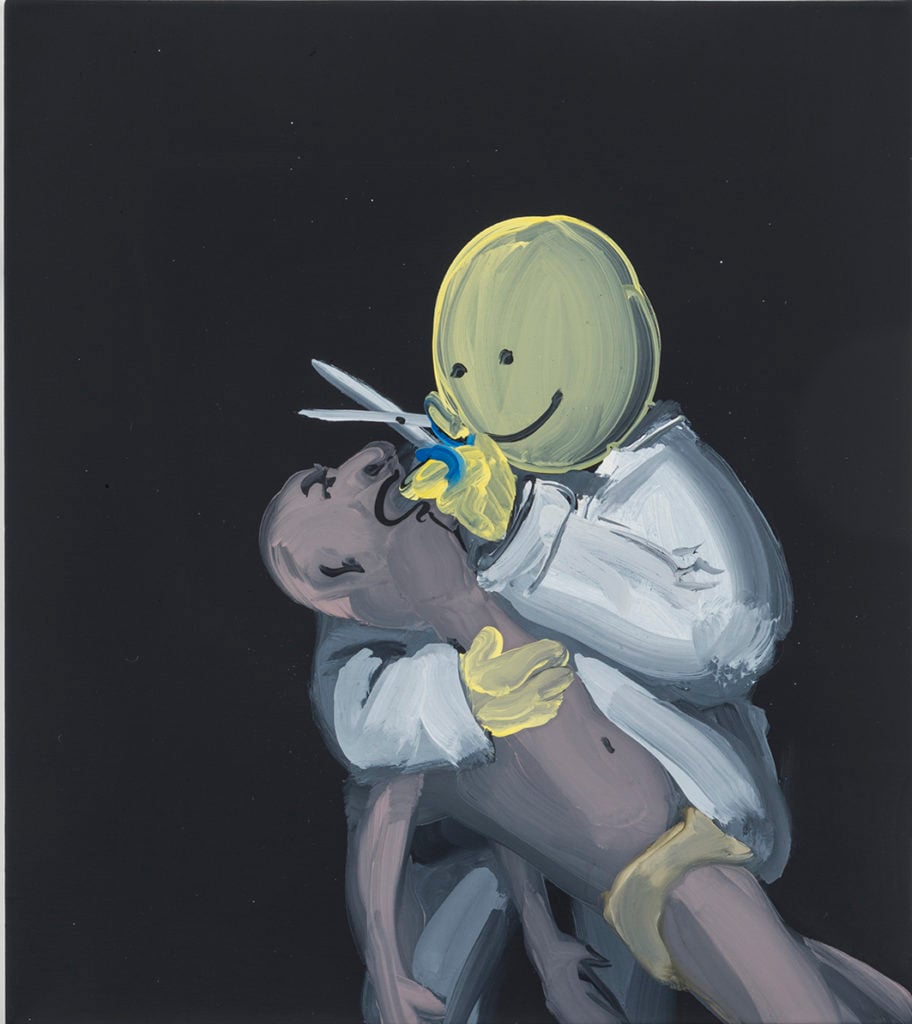

Tala Madani, The Ritual (2016). Photo courtesy Genevieve Hanson and Hauser & Wirth.

New Yorkers will recognize her work as the standout (along with that of Sanya Kantarovsky) of Hauser & Wirth’s summer show “A Modest Proposal” in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood. On opening night, people blocked the hall to crowd around the small screen playing Madani’s violent video, Wrong House (2015) in which each digitally animated visitor is beaten to death after knocking on the door of a—nude, balding and bearded—painted’s man’s house. (Given her overall interest in men, it’s surprising that she is not also in the group show, “The Female Gaze Part 2: Women Looking at Men,” down the street at Cheim & Reid.)

Madani is also showing work in “Invisible Adversaries” at the Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, NY through September 18; and “Malerei als Film” at Kunsthalle Darmstadt near Frankfurt through July 24. These two shows follow other recent group endeavors including: “Omul Negru,” curated by Aaron Moulton, at Nicodim Gallery at Cantacuzino Palace, in Bucharest; “Colliding Alien Cargo,” at Marlborough Chelsea in New York ; “Inside Out,” at Galerie Eva Presenhuber in Zurich; and the all-film and video show “Mixtape 2016” at her London gallery, Pilar Corrias. (Her upcoming show with Pilar Corrias opens October 5 and runs through November 16.)

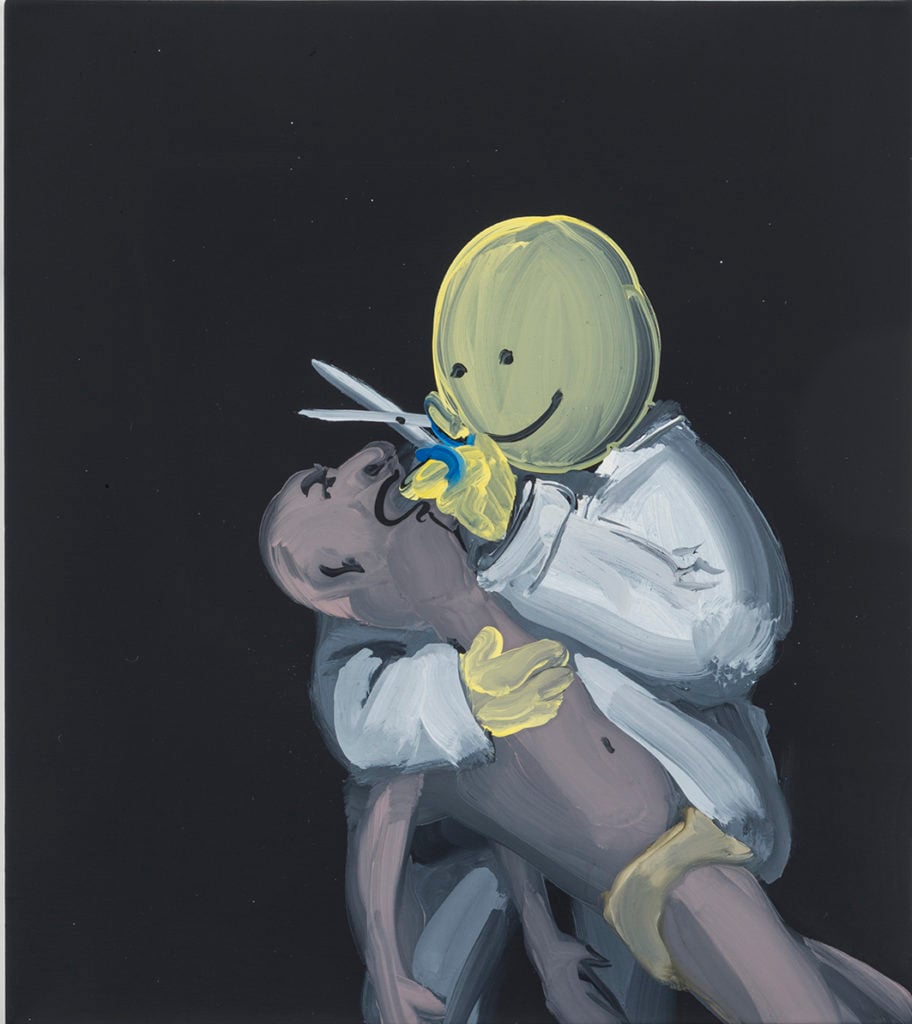

Tala Madani, Finding Zebra (2008). Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London.

It’s a shame that the Boston area was the last stop for “First Light”; the List’s show is a great introduction to an artist whose subject matter is challenging, especially for male viewers, and whose facility with paint is a thrill to behold.

“Some of these are quite naughty but overall they announce very clearly Tala’s signature themes,” said Henriette Huldisch, who co-organized the exhibit with CAM’s Kelly Shindler, while giving a private tour of the show at MIT.

Huldisch said she has observed men and women responding very differently to Madani’s work. Women nod knowingly, but not necessarily without affection, in recognition of men portrayed as vulnerable babies whose gestures, expressions, and stances are at turns plaintive, silly, angry, and clamoring.

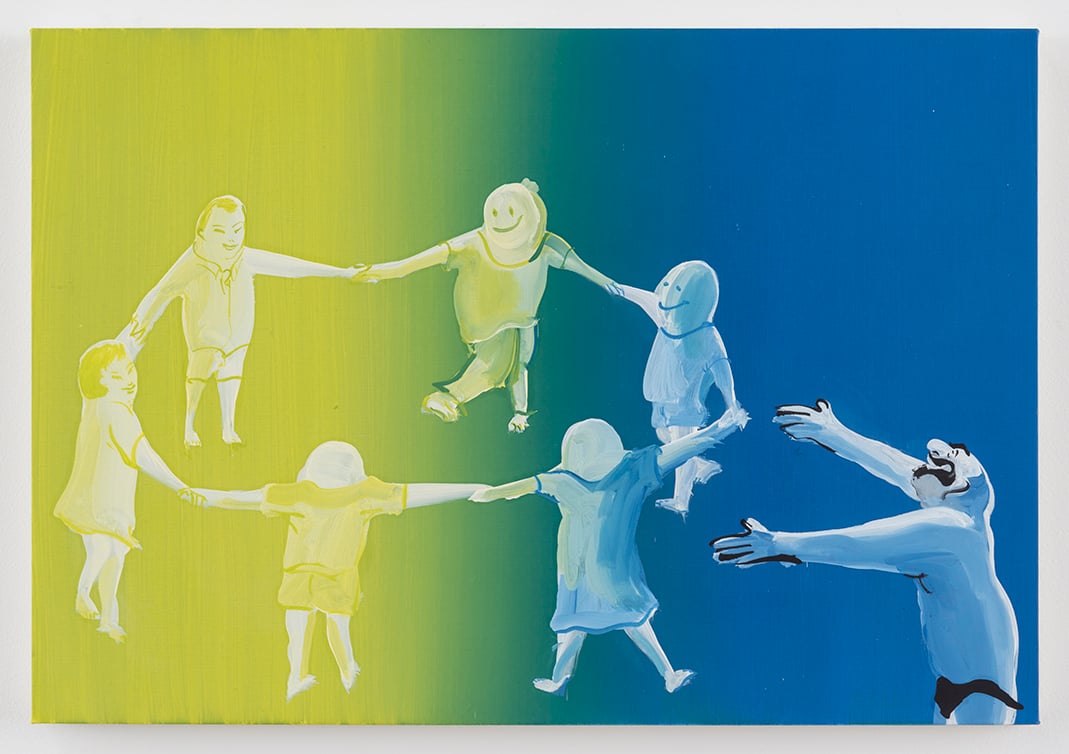

Tala Madani, Projections (2015). Courtesy the artist; David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles; and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London. Photo courtesy Josh White.

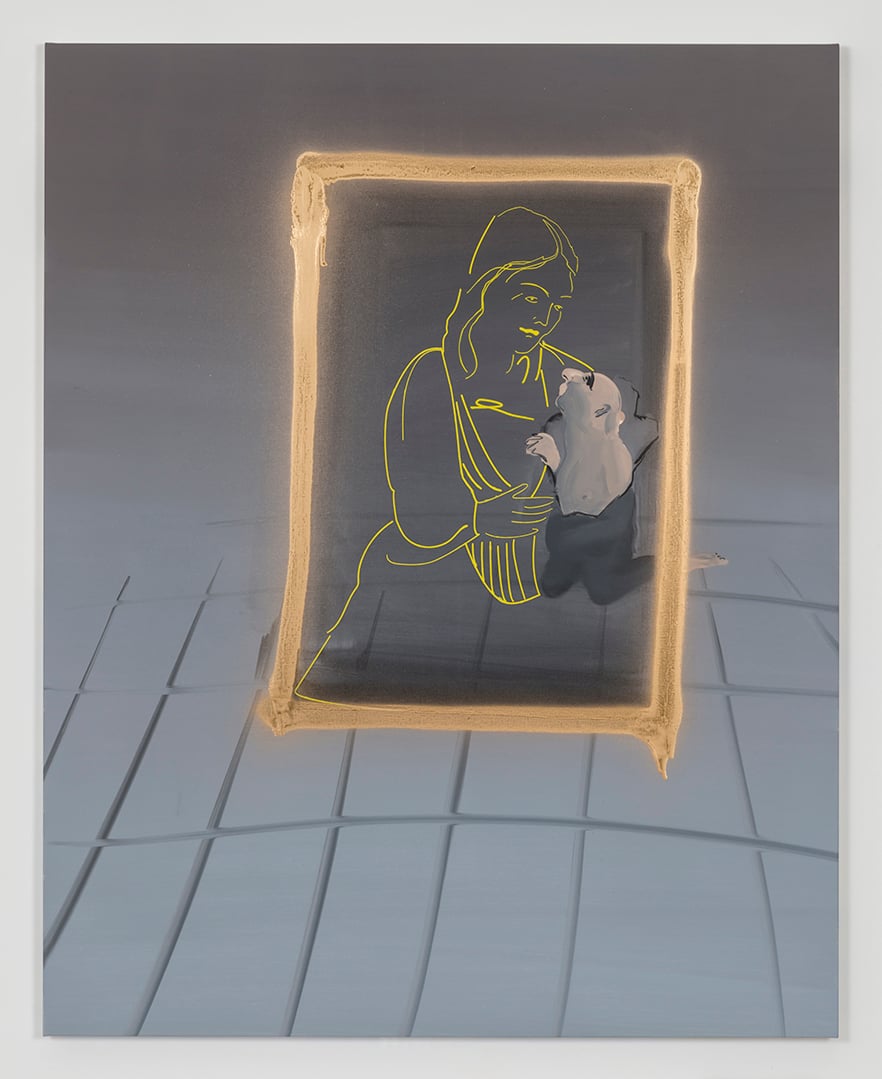

Madani infantilizes or feminizes her male subjects in several works. For instance, as in Twins (2015), they lactate, or they play out various roles in pietà poses as in Adoption (2015). Several of her works seem to reference Justin Timberlake and Andy Samberg’s 2006 digital short “Dick in a Box” from Saturday Night Live, as in Tree and Beards (both from 2015), where a man in a Santa hat is urinating through a hole in a gift box wrapped around his penis.

In an interview in the new Madani monograph from Prestel, the artist explains, “I like to think, after so many centuries of misogyny on canvas, that paintings of men being pushed and pulled wouldn’t cause so much defensiveness…” She continues, “People really associate caricature with some kind of belittling, when it’s actually a form of engagement.”

One man to whom I showed new book said it reminded him of his bewilderment—knowing men and himself as he does—that women ever are willing sleep with men, let alone love them.

Tala Madani, The Dance (2015). Collection of Laurie Mitchell and Brent Woods. Photo courtesy Josh White.

Critic Sebastian Smee objected more to the way Madani’s work at MIT’s List Center has been distilled into curatorial jargon in the exhibit’s accompanying collateral than to the artworks themselves, according to his review in the Boston Globe. Many of the works depict men playing with their penises, or with bodily matter such as urine, feces, and semen.

In the work Smee takes most to task, finding it “so desultory” that it falls flat, three men on their hands and knees each excrete a brown paint that flows together to form a Christmas tree. (It’s not surprising to learn that the artist finds the television show South Park, known for its scatological and political humor, “brilliant.”) Of course, Pier Manzoni created Artist’s Shit (Merda d’artista) over five decades ago, in 1961. But this didn’t stop the negative reactions to her work.

“My gallerist [Corias] sent it as a Christmas card and she had a bunch of people asking to be removed from the email list,” Madani said. She was surprised by the strength of people’s reactions. “Shit is actually quite a productive substance but people tend to read it as negative,” she says. “I find that interesting.”

Madani paints as if drawing; gestural brushwork and a sparing use of spray paint join her confident sense of line and playful sense of humor that evoke the famed 20th century cartoonist and writer James Thurber, most particularly his series “The War Between Men and Women.” In several of Madani’s works, including Dress Codes (2015), which is on loan from collector Beth Rudin DeWoody, the artist integrates Ben-Day dots from old newsprint comics, just as Roy Lichtenstein did.

Tala Madani, Adoption (2015). Collection of Sheldon Inwentash and Lynn Factor, Toronto. Photo courtesy Josh White.

Even Madani’s paintings feel as if on the verge of being animated. Most read like something’s happening or about to happen that means trouble. In several works that evoke Abu Ghraib (The X, The XX, or Becoming Brilliant, all from 2015), figures have the elasticity of Wile E. Coyote being tortured by the Road Runner.

“Growing up in Iran, I was watching a lot of Bugs Bunny, Tom and Jerry, and also Disney cartoons like Sleeping Beauty, Snow White, and of course Fantasia,” she recalled, but she also said she loved the internationally-acclaimed graphic novel Persepolis by Iranian illustrator Marjane Satrapi.

Madani finds a lot of inspiration in experimental film–both historical and current. “I watch a lot of Polish animation—it’s the best, it’s genius,” she said. She has created a dozen animated shorts so far, several minutes long at most. (In addition to the one at Hauser & Wirth, two others were on view in private screening areas at MIT.) In most, she uses stop-motion to capture paintings that she then wipes off and repaints to create, once edited, the sense of movement.

“All my films are short because of how long it takes to do,” she explained. “It takes me drawing or painting hundreds of images to make a minute and a half to a two-minute animation.”

Despite the demands of the genre, she is starting to make plans for a longer films. “I want to play with more cinematic tools next,” she said.