Reviews

Tarek Atoui Will Alter Your Aural Experiences at Bergen Assembly

A defunct swimming pool in Bergen is filled with unheard sounds.

A defunct swimming pool in Bergen is filled with unheard sounds.

Hili Perlson

The Snapping Shrimp is one of the loudest creatures in the sea. With a snap of the claw, it creates a captivation bubble that generates acoustic pressure capable of crushing a small fish—the shrimp’s prey.

On a small monitor placed on the floor, a 40-second, black-and-white sequence of the shrimp’s killer bubble moving through water is playing in slow-motion. In reality, its speed can reach almost 100 km/h, and release a sound nearing 220 decibels—all qualities that, for me watching the clip, will remain imperceptible. And that’s precisely why it’s here, displayed inside a disused public swimming pool, the Sentralbadet, in the heart of Bergen, Norway. It’s shown among other curiosities and phenomena—some invented by man, some naturally occurring—that relate to sound and its physicality, perceptible or not.

Titled “Infinite Ear,” the show—which also includes a film program, a café which pairs drinks with sounds, and a massage room (more on those later)—is curated by the duo Council who are Grégory Castéra and Sandra Terdjman, and Beirut-born sound artist and musician Tarek Atoui. Together, they designed an umbrella project that centers on the experience of deafness and the sensory transformation of hearing for the three-part, 2016 Norwegian triennial, the Bergen Assembly. (The triennial’s other two strands are curated by Praxes, who staged long-evolving shows with Marvin-Gaye Chetwynd and Linda Benglis; and freethought, a multi-headed research group which focused on the infrastructures governing modern life).

Tarek Atoui & Council, “Infinite Ear.” Installation view at Bergen Assembly 2016, Sentralbadet, Bergen. Photo: Thor Brødreskift

Atoui and Council first collaborated in 2013, on a workshop for students at a school for the deaf in Sharjah. But his own explorations of the different ways in which we hear began earlier on, and were impacted by an arrest in 2006, where he was interrogated and beaten in Lebanon, and suffered partial hearing-loss in one ear as a result.

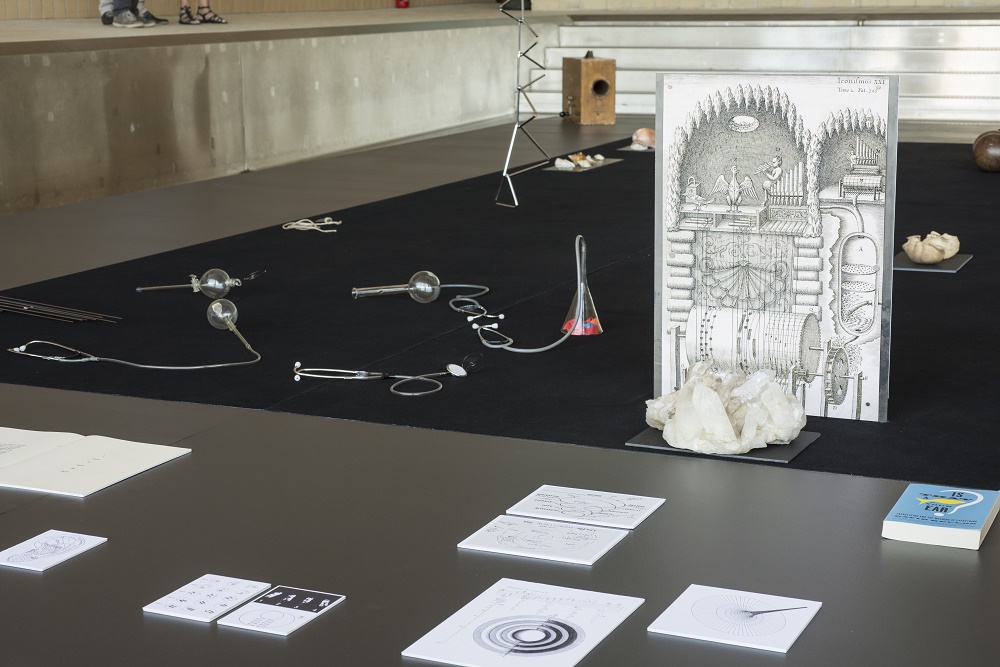

A long-time builder of instruments in his practice, Atoui created nine new tactile, vibration-heavy devices in collaboration with other instrument makers, as well as hearing impaired volunteers at workshops around the world. Throughout the month of September, the new instruments—including a network of subwoofers played with hand movements like a theremin, and a tactile keyboard that lets the musician listen with their fingers—are played in a series of concerts at Sentralbadet called “Within.” When not activated, the instruments are displayed inside the empty pool: handmade and sculptural, they are extremely inviting to the touch.

Tarek Atoui, “Within II”, Performance, Bergen Assembly 2016. Sentralbadet, Bergen. Photo: Thor Brødreskift

The performers include professional musicians and non-trained performers, deaf and hearing impaired. So successfully designed are the instruments that watching the second series of concerts, “Within II,” it was mostly impossible to make out who on stage was differently hearing. During one sequence, performed by three women who I later found out were all non-hearing, Atoui was moving to the music as he watched the concert from the railings around the water-less pool.

Tarek Atoui, “Within I” Performance, Bergen Assembly 2016, Sentralbadet, Bergen. Photo: Thor Brødreskift

Atoui and Council mounted an experiential exhibition that makes use of the functional architecture of the massive 1960s-era public pool. It seems crucial to activate the space wisely as a place for art and culture, as the city is currently weighing different uses for the site which shut down about two years ago, and it could very well end up as a shopping mall.

The main pool is the concert hall, the kiddie-pool is filled with objects, there is a screening room showing a series of films on hearing, sign language (Christian Marclay’s Mixed Review from 1999), and audio forensics (Lawrence Abu-Hamdan’s Rubber Coated Steel, 2016). A separate room in the front is dedicated to sound therapy sessions, which apart from being very relaxing, demonstrate that hearing occurs beyond the aural, and with our entire body. Thierry Madiot has perfected the technique over the last 16 years, and uses a large wooden table where the patient lies, and an array of metal and wood instruments played by two or more therapists.

Tarek Atoui “Within,” Sonic Therapy Sessions, Sound Massage with Thierry Madiot and guests, Sentralbadet, Bergen Assembly 2016. Photo: Thor Brødreskift

After being treated to a soothing sound massage, I walked over to the White Cat Café—which borrows its name from the curious fact that all deaf cats happen to be white—installed in the pool’s old cafeteria. Browsing the sound and drink menu I noticed that the snapping shrimp was on offer, along with acoustic delicacies such as the slow erosion of a rock, or an evaporating puddle. I ordered the pistol shrimp sound along with the recommended matching drink and leaned against sub packs installed on the back of the seats. (Usually used for recording studios, the packs allow you to feel the sound at certain volumes). Though much less sensitive than my ears, I was finally listening, with my body, to the thump of the shrimp’s snap.