Law & Politics

The MFA Houston Can Keep a Bellotto Painting That the Heirs of a Jewish Collector Say Is Rightfully Theirs, a Judge Has Ruled

The judge dismissed the lawsuit brought by heirs of a German Jewish collector.

The judge dismissed the lawsuit brought by heirs of a German Jewish collector.

Sarah Cascone

A federal judge has dismissed a lawsuit against the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston that called for Bernardo Bellotto’s Marketplace at Pirna (ca. 1764) to be returned to the heirs of Max Emden, a Jewish department store owner who sold it to Nazis in 1938.

The judge, Keith P. Ellison of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas Houston Division, did not weigh in on whether the sale was made under duress, but found it could not be returned because of a legal technicality, according to the Houston Chronicle.

The ruling cited the Act of State doctrine, which prevents the court from overturning any legal decisions issued by a foreign government—even though both states have pledged to return property seized by the Nazis to its rightful heirs.

“It seems natural to ask why the mistake by the Dutch government would take priority over the Washington Principles. But it’s ultimately not the mistake that takes priority, but the fact that it was a ruling by a foreign state. So it comes down to balancing the Act of State Doctrine with the Washington Principles,” art and cultural heritage lawyer Leila Amineddoleh, who was not involved in the case, said in an email to Artnet News. “The Washington Principles are just that—principles that inform restitution decisions. However, the Act of State doctrine is a doctrine in U.S. law that dates back many centuries.”

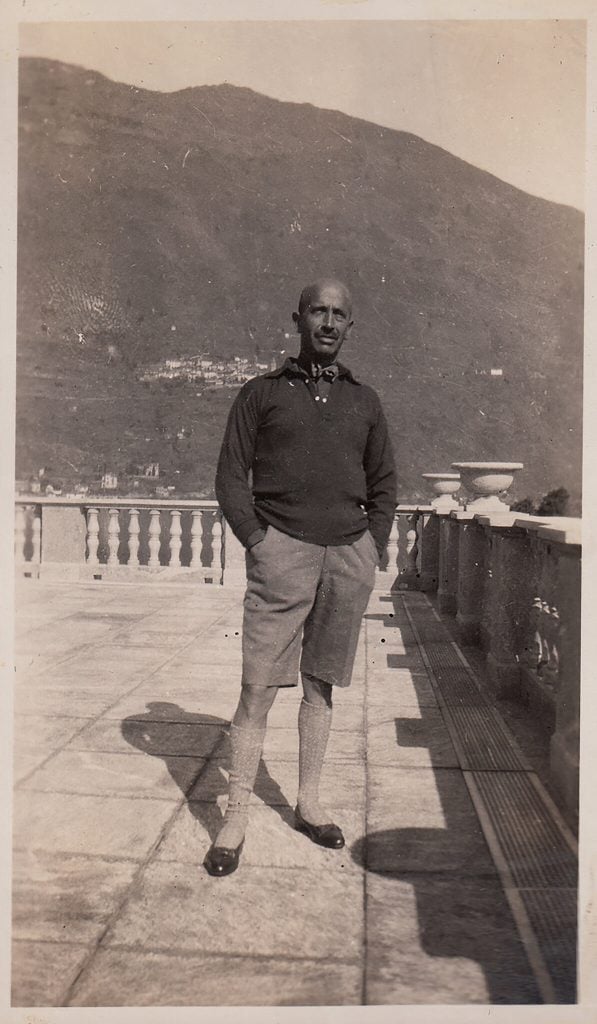

Max Emden sold three paintings by Bernardo Bellotto to an art dealer representing the Nazis in 1938. Photo courtesy of the heirs of Max J. Emden/Monuments Men Foundation.

The case, as is common with Holocaust-era restitution disputes, is a complicated one.

In 1938, Emden was living in Switzerland, but his finances were severely depleted due to the Nazis having seized his assets in Germany. He hired a dealer to help him sell three Bellotto paintings from his collection. The buyer was art dealer Karl Haberstock, who was collecting for Adolf Hitler’s unrealized Führermuseum in Linz, Austria. The Nazis hid the paintings in an Austrian salt mine, where they were later recovered by the Monuments Men, an Allied division dedicated to safeguarding cultural monuments during the war.

In 1946, Dutch officials contacted the Monuments Men seeking the return of Marketplace at Pirna on behalf of a gallery that had lost its inventory to Nazis. What the Netherlands didn’t realize was that the lost painting was actually a copy by an unknown artist, titled After Bellotto.

Upon receipt of the original Bellotto that had belonged to Emden, the Dutch government restituted it to German art dealer Hugo Moser, who claimed it was his, in 1948—and when the Monuments Men realized the error a year later, it was too late.

Moser sold the painting in 1952 to Samuel H. Kress, a U.S. collector, who would go on to donate it to the MFA Houston through his foundation. The Emden heirs argue that Moser knew he was selling someone else’s painting, and that he fabricated a false provenance to do so.

But in the new ruling, Judge Ellison focused on the Netherlands’ role in returning the work to Moser, finding that the U.S. had no authority to overturn the act of a foreign government, even if it was carried out in error.

“Reaching into the Dutch government’s post-war restitution system would require sensitive political judgments that would undermine international comity,” Ellison said in his decision.

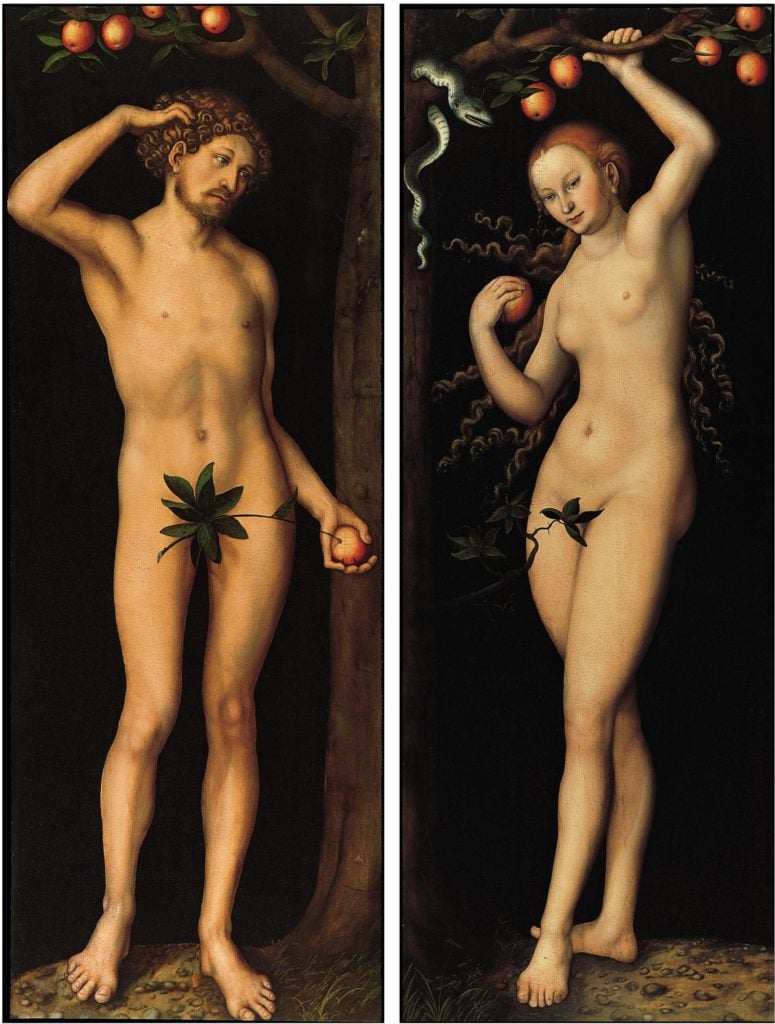

To determine whether the restitution of Marketplace at Pirna to Moser was a sovereign act on the part of the Netherlands, the judge cited the 2018 ruling Von Saher v. Norton Simon Museum of Art at Pasadena. In that case, the Dutch government sold a pair of Nazi-looted Lucas Cranach the Elder Adam and Eve paintings in 1960 to George Stroganoff-Scherbatoff, who claimed to have owned them prior to the Russian Revolution.

Years later, the heir of Dutch Jewish dealer Jacques Goudstikker, who had been forced to sell the paintings to Nazi leader Hermann Göring, sought their restitution, but lost the case on the basis of the Act of State doctrine in 2018. The Supreme Court denied Von Saher’s appeal in 2019.

“It is a sad blow to the plaintiff for Von Saher to be cited, because many people believe that case was wrongly decided,” Amineddoleh said.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Adam and Eve (circa 1530). Courtesy of the Norton Simon.

Adding salt to the wound, had the Monuments Men not mistakenly turned Marketplace at Pirna over to the Netherlands, the work would have remained in Germany along with Emden’s two other paintings by the artist. In 2019, Germany’s advisory commission on Nazi-looted art found that those works had been part of a forced sale, and the nation restituted both pieces.

In its case against the Emden heirs, the MFA, Houston maintained that the work was not, in fact, sold under duress.

“We acknowledge the recommendation of the panel and the decision of the German government, but that decision does not alter the facts or voluntary nature of Emden’s 1938 sale of the Bellottos,” a museum spokesperson told Artnet News in an email.

“We have extensive documentation that in 1938 Dr. Max Emden, a Swiss citizen and resident, initiated the voluntary sale of our painting, from the security of his Swiss home and island, and was paid his asking price in Swiss currency,” the museum said in a statement. “The judge’s decision affirms our good title.”

The Monuments Men Foundation, which continues the work of the original Monuments Men and conducted the research that unraveled the tangled provenance web surrounding the picture in an effort to aid the Emden heirs’ restitution efforts, did not agree.

“Regardless of any court ruling, a painting once owned by a German Jew, stripped of his assets by the Nazis, now hangs in one of our nation’s wealthiest museums because of a 1946 clerical error and a 1951 fraud,” the organization said in a statement to Artnet News. “The museum knows these facts by now. Instead of a demonstration of grace, we have an example of greed: the museum paid nothing for the painting.”

“While the Monuments Men Foundation is disappointed by the court’s ruling,” the statement added, “this is by no means the end of the case nor the MFA’s moral imperative to restitute the Bellotto painting to the Emden family.”