Art World

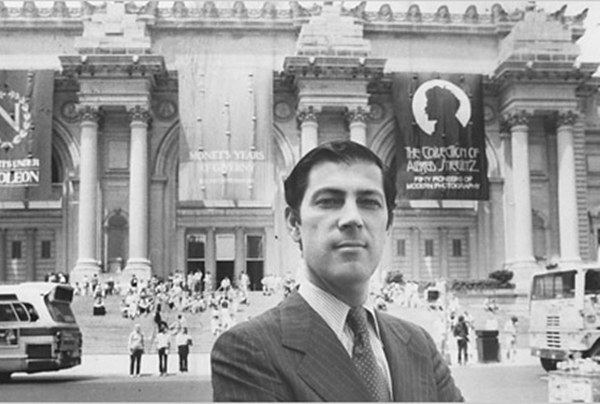

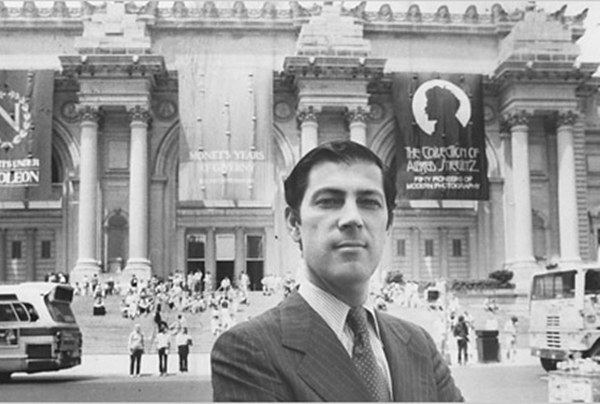

That Time Philippe de Montebello Was in a Florence Flood

Back on the day the Arno flooded, a 30-year-old de Montebello got covered in mud.

Back on the day the Arno flooded, a 30-year-old de Montebello got covered in mud.

Rozalia Jovanovic

As the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s director for over 30 years (1977–2008), Philippe de Montebello was known for stewarding the museum through an expansion (it nearly doubled its size to 2 million square feet), through important acquisitions including Renaissance master Duccio di Buoninsegna’s Madonna and Child (famously acquired for over $45 million), and for creating significant new exhibition spaces like the Carroll and Milton Petrie European Sculpture Court. But what you may not know is that de Montebello was in the catastrophic Arno flood in Florence in 1966. Millions of masterworks of art and rare books were destroyed as a result.

De Montebello recounts his experience in Rendez-vous with Art (published by Thames & Hudson and released Tuesday), a frank, entertaining, and highly readable compendium of conversations between himself and British art critic Martin Gayford as they visit museums in seven cities across the US and Europe contemplating the way we look at art in public places. “One can be taught, and needs to be taught, how to look,” writes de Montebello, “how to put aside one’s prejudices, one’s overly hasty negative reactions.”

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Madonna and Child, ca. 1290–1300. Tempera and gold on wood, overall, with engaged frame 27.9 x 21 (11 x 8 1/4); painted surface 23.8 x 16.5 (9 3/8 x 6 1/2). Image credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Rogers Fund, Walter and Leonore Annenberg and The Annenberg Foundation Gift, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, Annette de la Renta Gift, Harris Brisbane Dick, Fletcher, Louis V. Bell, and Dodge Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, several members of The Chairman’s Council Gifts, Elaine L. Rosenberg and Stephenson Family Foundation Gifts, 2003 Benefit Fund, and other gifts and funds from various donors, 2004 (2004.442). Image Metropolitan Museum of Art.

From the Louvre to the Prado, the two discourse on a variety of subjects from the benefits of seeing religious artworks in the sacred spaces for which they were originally created to the phenomenon of the “museum-age gaze,” or our tendency to look at works comparatively, to the drawbacks of seeing highly popular works in museums. When visiting Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring at the Mauritshuis, de Montebello humorously decried the practice of plastering the entrance with posters of the famed work, which he said ruined the experience for him. “You would be much better off in an armchair,” he quipped, “with one of those books from the 1940s and 1950s with superb black-and-white photos.”

Back on the day of the Arno river flood, a 30-year-old de Montebello, on a travel grant from the Met, learned a lesson of a different sort. He began his day looking forward to a lunch date with “aesthete and connoisseur” Sir Harold Acton and ended up in the Piazza del Duomo helping conservators in the Baptistery where works like Donatello’s St Mary Magdalene were covered in mud. In one of the most gripping chapters of the book, Gayford and de Montebello visit the Museo dell’Opera di Santa Croce and the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, where the two discuss the significance of change and the experience of viewing damaged art and de Montebello recounts his harrowing experience. Here’s an excerpt:

RENDEZ-VOUS WITH ART

by Philippe de Montebello and Martin Gayford

It is not just the fragments in museum collections, but whole cities that are so beloved that we strive to keep them going, wishing them to remain as far as possible unchanged, even perhaps – impossible as it is – to try to make them more the way they once were. David Hockney has observed that things survive, broadly, for two reasons: either because they are made of some substance so hard it resists the effects of time, or because somebody loves them. That ‘somebody’ is often a corporate entity, such as a museum or organization: for example, the Soprintendenza of cultural property in Tuscany.

We were reminded of that fact on our Florentine visit when we wandered into the museum attached to the Franciscan basilica, the Museo dell’Opera di Santa Croce. This is in the old refectory of the friary and is filled with notable masterpieces of painting and sculpture. The building, and the great church itself, are in one of the lowest-lying parts of the city, close by the Arno. When the river catastrophically broke its banks in November 1966, both Santa Croce and the museum were filled with a churning mass of water, oil and mud. It did a great deal of damage, and almost totally destroyed some works.

PdM Among the victims of the 1966 disaster, one work stands out and that is the great Cimabue Crucifix.

This imposing, even massive, work is a precious relic from the very dawn of the Renaissance, the moment when humanity and realism began to seep into the formulas that Italian artists had inherited from Byzantium. The swirling flood stripped the paint from much of the surface, particularly from the face and body of Christ. Years of careful restoration followed, but done is such a way as to leave the areas of damage clear and obvious. The effect – Philippe and I agreed – is so visually disruptive as to make it almost impossible to experience the Crucifix as a work of art.

PdM Although many options were available to conservators, such as judicious in-painting to reduce optically the traces of the damage, which photographs of the work before the flood would have permitted, the Crucifix was left with its open wounds. It was singled out by the authorities to be the sacrificial and poignant memorial to the disaster, a bit like how, after the Second World War, the bombed-out Kaiser Wilhelm church in Berlin was left in its ruined state.

There are, unnoticed perhaps by most visitors, constant efforts to preserve the objects we see in museums – and elsewhere. This is, in Hockney’s summary, the equivalent of the collective love we feel for certain fragments that have been preserved from past ages. Love, however, can be expressed in many ways, tough and tender. ‘Conservation’ and ‘restoration’ come, too, in a multiplicity of gradations, from gentle to intrusive, from cautious cleaning to radical, even drastic, restoration. Although many of the techniques involved are scientific, the final decision on the degree of intervention is often a matter of taste.

In the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, which we visited after lunch, Philippe suddenly paused in front of Donatello’s extraordinary life-size carving of the Magdalene. It acted as the madeleine soaked in tea famously did on Marcel Proust, as the sight of the sculpture unlocked the doors of memory and took him – and us – back almost fifty years.

PdM Donatello’s St Mary Magdalene was not here, but inside the Baptistery when I first saw it, and it was then half covered in mud. I was in Florence on a travel grant from the Met in the Fall of 1966. It was late September when I arrived, and among the introductions I had was one to the aesthete and connoisseur Sir Harold Acton whose splendid villa, La Pietra, now belongs to New York University. He invited me to have lunch there on 5 November.

However, my little story starts in the early hours of the day before, the fourth, when after days of torrential rain, the Arno began to swell and threatened to burst its banks. That morning, I was actually crossing the Ponte Vecchio on the way back to my pensione in the Via dei Calzaiuoli when the waters did burst the river’s banks. So I ran to the pensione, barely keeping ahead of the rushing waters; in fact, I may already have had wet feet and it was pouring rain, of course. At the pensione, we all moved upstairs and from my balcony I had a view toward the Piazza del Duomo, specifically the area between the Baptistery and the Duomo.

I could see the rushing water carrying cars and furniture down the street at great speed and, to my horror, slamming against the doors of the Baptistery, the so-called Gates of Paradise, that glorious testament to Renaissance innovation and genius. All of us stayed on the upper floors upstairs until the next morning when the water began to recede. The first thing I did is rush to the piazza, where there was total chaos, with people milling about in shock. I was walking through mud halfway up my calves, but managed to make my way to the Baptistery.

The east doors had been sprung open; the Ghiberti panels were partly detached and one or two were actually lying flat on the ground in the mud. There were no officials there, no police, but a few museum people in a daze to whom I showed my Met ID. The first thing I saw when I walked in was Donatello’s Magdalene. She was still standing immediately on the left, I think, as you came into the Baptistery. She was black with mud up to about the level of her hands, somewhere around there. There were a couple of other sculptures, also covered with mud. They removed her very quickly; by the next day or two, I think, she had gone. After all, she must have been high on the list of works to be rescued. So you see, she and I have encountered each other before.

That was the day of my lunch with Sir Harold, and my first thought was, What am I going to do? Because of course there was no telephone, there were no vehicles, there was no means of communication, no way for me to call and cancel. So I decided I’d walk the three or four kilometres up to La Pietra.

I rang the bell, probably late and looking a sight; the footman opened the door and I said, ‘I’m Philippe de Montebello’. He looked at me, incredulous, and asked, ‘Aren’t you coming to have lunch with Sir

Harold?’ I said ‘Yes’. He responded, ‘Looking like this?’ Of course, they had no idea of what had happened down below. I told him that the Arno had flooded and that there was a disaster in Florence. He said, ‘Oh, oh’, called Sir Harold, who came and said, ‘Young man, I was about to say one dresses up to come and see me’. I explained in a few words that there’d been a terrible flood and the Ghibertis were lying in the mud.

Naturally, we never had the lunch. He called his chauffeur, then we rushed and got into his car and drove as close to the city centre as we could. Sir Harold put on his hunting boots and we walked down to the Piazza del Duomo, and entered the Baptistery. When Sir Harold saw the Magdalene, the Donatello, he just stood there and wept.

Over the next few days, I helped curators and conservators move things around, but there came a time when there were so many volunteers that they got in the way, and I left when my travel grant expired. Eventually, most of the frescoes that had been affected by the flood were saved, carefully peeled from the walls through the strappo da muro technique (pulling from the wall) and then in-painted using the tratteggio technique of hatchings, mostly for tonal harmony, rather than attempting precise but inevitably inexact transcriptions of details. There was one beneficial result of the tragedy: the discovery under a number of frescoes of elaborate preparatory drawings, called sinopie from the red earth pigment (sinopia) used to make them.

Excerpted from Rendez-vous with Art, by Philippe de Montebello and Martin Gayford.

Copyright © Thames & Hudson Ltd, London. Philippe de Montebello Text © 2014 Philippe de Montebello. Martin Gayford Text © 2014 Martin Gayford. All rights reserved.

Reprinted by permission of Thames & Hudson Inc, www.ThamesAndHudsonUSA.com