Museums & Institutions

Can the Andy Warhol Museum’s Pop District Be a Model for Civic Engagement by Arts Institutions?

Launched in 2022, the project is now entering its second phase of development.

The Pop District at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh is entering its second phase of development of a model that the museum believes demonstrates how institutions can embrace professional development and civic engagement for viability.

The project is the brainchild of associate director Dan Law and launched in 2022. It includes the development of a six-block section in the museum’s neighborhood on Pittsburgh’s North Shore, including the Warhol Academy, a workforce development program, as well as the boutique production studio the Warhol Creative and the Factory, a creative arts center expected to host 100 live performances a year. In its first phase, the site has also installed five public artworks including Yoko Ono’s Wish Tree and Mikael Owunna’s Anatomy of the Human.

“It’s not unfair to say every single museum in America is facing a relevancy problem. We’ve built castles dedicated to fine arts, but they’re intimidating. They are not in touch with community needs,” Law told me during a visit to the site. “Museums can run world-class art programs, but they also can deploy robust community development strategies. They’re not mutually exclusive.”

A Civic Mission

The Pop District aims to contribute $100 million in annual economic impact to the community, sustain 200 annual participants through workforce programs, and provide direct revenue that supports and sustains the museum. In a recent accounting, the project has reported generating more than $3 million in wages, fellowships, and contracts in the local economy, while matriculating upwards of 100 students through the Academy. Zooming out, such an injection might help stimulate the local economy, said Law, to help address socio-economic challenges in a city that was ravaged by the closure of steel mills in the 1980s.

As an example of the project’s civic engagement, he pointed to the Pop District’s relationship with local group River Life, which aims to conserve Pittsburgh’s three rivers. The nonprofit is aiming to reimagine a small riverfront park just outside the Pop District’s property, where the museum holds open-air music festivals, to enliven the riverfront experience. The county and local governments are also renovating the city’s three main bridges with digital lights to illuminate them at night.

“Our theory is public art and culture experiences are the connective tissue. And River Life is like, ‘We agree.’ So that’s a practical example of how this works in places like Pittsburgh,” Law said.

The Andy Warhol Museum’s Pop District. Photo: Elisa Cevallos.

Law added that the rest of the Carnegie Institute—the Carnegie Museum of Art, the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and the Carnegie Science Center—are onboard with the Pop District’s mission, coming all the way down from Steven Knapp, the president of the organization. “He wants every single one of our museums to look at what’s inside our four walls, put it down on the street, and drive that value into neighborhoods,” he said.

The Warhol Museum team has also looked at other examples of how cities and organizations leveraged development to boost the economy. In particular, they have an eye on the Los Angeles Arts District and the Mission District in San Francisco. The NEW INC incubator at the New Museum in New York, said Law, also offers a “wonderful example of technology and arts with new economy and neighborhood creative placemaking development.”

“But one of the most germane is the connection between downtown Detroit and Midtown Detroit. Detroit’s a city of 39 square miles. About 10 years ago, there was downtown, then there was like a prairie, and then Midtown,” he added. “They’re using artists to bridge that gap.”

In Warhol’s Spirit

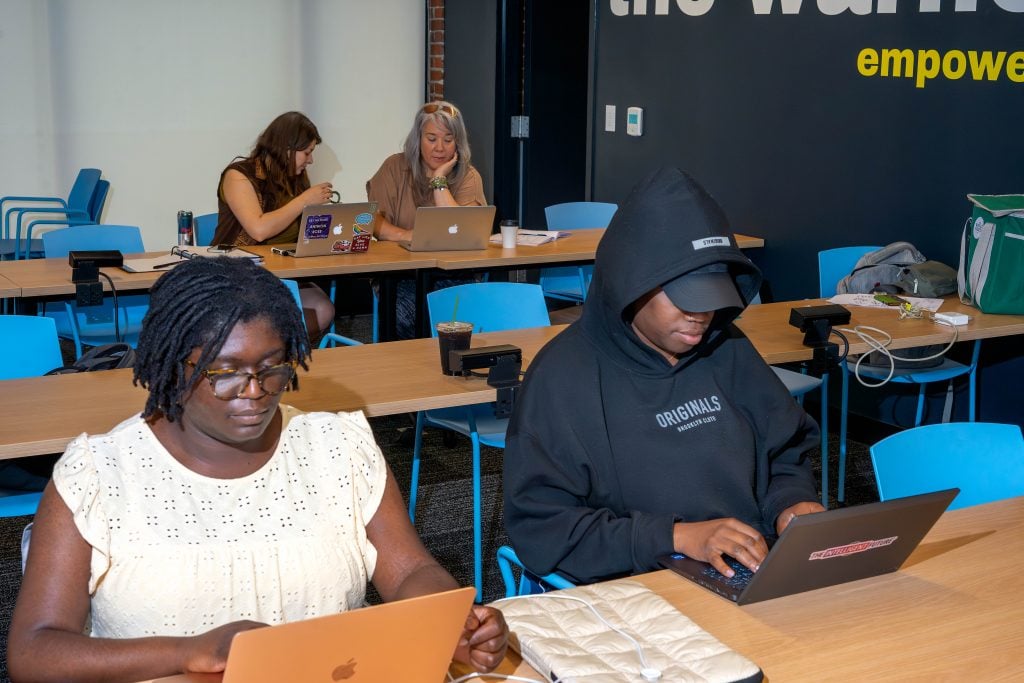

Students working on a certificate course at the Warhol Museum’s Pop District. Photo: Adam Schrader.

To the museum, the Pop District furthers its goal of sustaining Warhol’s art and legacy. Pittsburgh does not boast a gallery system or a large art market, Law conceded; but while the Pop District “can’t fill the gallery space,” he hopes it can be helpful to those who can.

Since 40 percent of the real estate around the Pop District is empty, Law believes the museum be a leader or facilitator matching artists with a patron network to help grow the fine art economy in the area. It might go some way toward stemming the flow of college-educated people who leave the city after graduation (much like Warhol departed Pittsburgh with his close friend and fellow artist Philip Pearlstein in 1949).

Meanwhile, the Warhol Academy has been offering workforce development opportunities to its participants since 2021, including more than 60 fellowships in digital content creation and post-production. The Pop District has held professional development workshops with Brewhouse Arts and a fabrication shop called Proto Haven in the East End of the city, while the Warhol Creative serves the museum with creative content, including a brief documentary that aired at its 30th anniversary gala.

Law said that everything, including lessons taught at the Academy, is in the spirit of the late artist. “Everything is based on Warhol’s career. Part of the fellowship experience is to go through the museum and figure out original storytelling through Warhol’s legacy,” he said.

“We’ve been taught for 25 years that the mantra of this museum has been ‘More Than A Museum,’” he added. “Now the Warhol’s uniquely positioned to run a world class art program and robust community and civic engagement because of our namesake. It’s our most unique inheritance because Andy just constantly reinvented himself and redefined himself.”

Even the Academy’s offering of digital content as opposed to traditional art classes, said the Warhol’s outgoing museum director Patrick Moore, is in line with an artist who once divined 15 minutes’ worth of fame for everyone. “Warhol is one of the rare artists where I think [digital marketing] makes sense with his legacy,” he said.

Brian Donnelly, the artist known as KAWS, whose exhibition “KAWS + Warhol” just opened at the museum, commended the museum’s educational efforts. “I think art should be in every school,” he said. “I don’t think there’s any way you can’t walk away with some sort of addition to your skill set if you come and just get into thinking creatively.”

A Calculated Risk

But the Pop District is not without its detractors. While still in its infancy, the project came in for criticism by local NPR affiliate WESA in a December report in which anonymous “high-level staffers” spoke out after leaving due to disagreements over the new venture.

“The museum has been taken over by the alien that is the Pop District,” one unnamed employee told the radio station. Some felt that the museum was mounting fewer exhibitions of Warhol’s work and that, when shows went up, they fell short of professional standards. Others felt it was a “dramatic departure” from the museum’s mission.

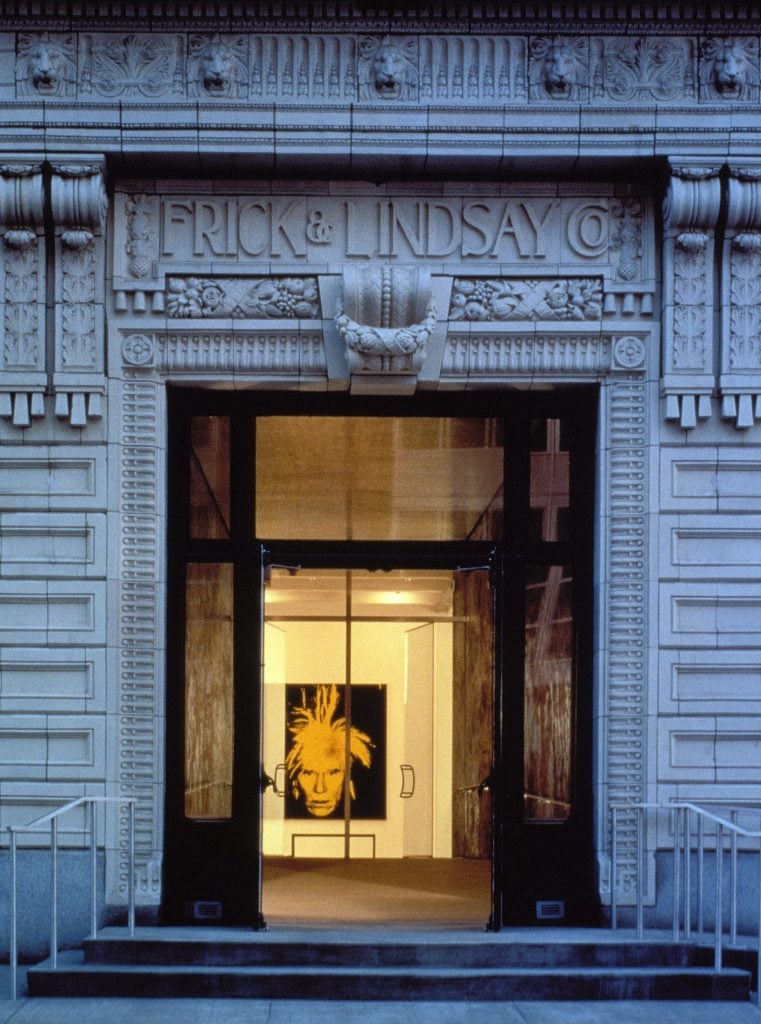

The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Photo: Remi Benali / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

Law dismissed the concerns raised and said he wished that WESA had spoken to him rather than citing a slew of anonymous ex-staffers. He defended the project by highlighting how it has already materially benefited the museum and the city’s creative community. The Pop District, he said, is currently exceeding each of its goals and is working to compile its data proving so for a report to be released in June.

“I don’t think it’s a controversial statement that the art world is categorically conservative, and its core behavior is conservative and risk-averse. This pushes directly against that,” Law contended. “We said we’d do $1 million of wages back into the community. Last year, we did $1.5 million. We said we’d offer 50 jobs, whether full-time, part-time or project-based. We’ve provided over 400 in three years.”

He added: “The giant 800-pound gorilla in the room is the economics of all of this. At the end of the day, artists need to make money to survive. They need to pay their rent. They need to pay their mortgage. They need to feed their families. And institutions have access to that money and those resources.”

He recalled how civic leaders in the ’80s were able to pull the city out of “rock bottom” after its steel-making capacity was decimated, but are now afraid to rock the boat, a wariness that is reflected across the country. “There’s an aversion to change and a fear of risk-taking,” he said. “But I think what we’re proving in real time here [that] calculated risk-taking is good, it’s healthy.”

Still, Law acknowledged that the Pop District is a fundamentally disruptive idea, which means the museum must continue to make the case for it to stakeholders. It’s a task Law has earmarked for its following stage.

“The next phase is convincing the art world this belongs, convincing the broader museum industry that this translates to the way we do things collectively,” he said. “But the community buy-in is done.”