People

The Art World at Home: Jacqueline Terrassa Is Preparing for Her New Museum Director Job in Maine and Cooking Mushroom Paella

The newly appointed director of the Colby College Museum of Art tells us about how she is keeping busy at home.

The newly appointed director of the Colby College Museum of Art tells us about how she is keeping busy at home.

Artnet News

The art world is slowly coming out of lockdown, but many decision-makers and creatives are still staying close to home. In this series, we check in with curators, historians, and other art-world professionals to get a peek into their day-to-day.

Jacqueline Terrassa is not wasting time in between jobs.

The decorated museum educator was named the Carolyn Muzzy Director of the Colby College Museum of Art earlier this summer. Before she arrives on the Maine liberal arts college campus in October, she is splitting her time between her hometown in Puerto Rico and her home base of Chicago, where she served until recently as the vice president for learning and public engagement at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Terrassa opened up to Artnet News about how she’s preparing to take the helm of an art museum in the middle of lockdown, what she’s reading to stay centered, and how she’s thinking about leadership in this complex moment.

What are you working on right now?

My main project is transition, and by transition I mean reflecting and readying myself. You find me leaping, so to speak. In fact, I just arrived this week in Puerto Rico where I am visiting family and re-centering, which is an early step in this project. My last day as vice president for learning and public engagement at the Art Institute of Chicago was August 6. I officially start at the Colby College Museum of Art as its director on October 5.

Walk us through the when, where, and how of your approach to this project on a regular day.

Closure matters, as do beginnings. I am taking time to connect with people who have been important to me and I’m beginning to reach out to people I want to get to know in my new situation. I now spend a couple of hours a day on calls and emails with people in my new Colby College community—initially these include board members, staff, peers.

Aside from this relationship piece, I am taking time to absorb what has happened in my life and the world in recent years, months, and days, to pay attention to what is happening now, and to begin to enter a new reality. This new place includes a new context altogether: a new state, a new geography, a new community, a new institution, a new social and political environment, a new demographic situation, even a new social contract around COVID, because Colby is reconvening this fall by putting in place a research-based program that involves frequent testing, isolation (as necessary), social distancing, and other mitigation efforts, as well as community agreements to work together to have a safe and successful semester.

There is a good amount of list-making going on. I find myself in movement, which either bubbles things up or allows things to sift and settle depending on the day: walking, running, swimming in the ocean (while I have it near), biking, and packing. I really think that to do a good job as a leader, I need to be very present with my whole being, very alert, very aware, very ready.

And that’s the other piece. I try to read and listen to people who offer well-researched information and ideas in order to grapple with our multiple, interlocking crises. Lots of people in the museum field are going through really tough times. Making space to hear what’s going on and to support my museum and art-world friends is important to me. I have been there and know how hard and isolating it can be.

What is bothering you right now (other than the project above and having to deal with these questions)?

“Bothering” is too light a term for the anger I feel in relation to the systematic dismantling of our democracy; the racist, sexist, and ableist neglect and violence put into motion by too many people in power; the rampant corruption; and the destruction of our social infrastructure, from education to health to food access to housing to employment and wages. I worry about November and its aftermath, regardless of the outcome of the elections. The situation in Puerto Rico also concerns me deeply; it reflects the larger issues I just mentioned, but keyed-up at a higher intensity.

I am troubled by the deep polarization I see everywhere, including within the museum field and the art world. All parties seem to be focused on optics. Visible symbolism matters, but so does productive dialogue, including disagreement and debate, along with steadfast attention to how insidiously racism and other forms of oppression seep into our everyday decisions, behaviors, and actions. We have to stop performing in order to see what we’re doing and truly listen. None of us is exempt.

Photo courtesy of Jacqueline Terrassa.

What was the last thing that made you laugh out loud?

Very recently, while on a bike ride in Chicago’s Jackson Park, a friend and I came across a little scene: a pond surrounded by very lush green trees and grasses, a small bridge, a pink heart-shaped balloon tied to the handrail, and an inexplicable tag penned in white chalk, in Spanish: gafas. I texted it to another friend immediately. Without missing a beat he wrote back: “Is that your tag?”

Are there any movies, music, podcasts, publications, or works of art that have made a big impact on you recently? If so, why?

Just at the start of 2020, I read Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds by adrienne maree brown. I am a very physical reader, and just about every one of its pages now features a folded corner and underlining. The book offers conceptual models for organizing and moving forward human-centered work. brown makes a case for adaptation, iteration, responsiveness, interdependence, self-care, and collaboration as necessary strategies.

Then there’s poetry. I’ve recently received several poems as gifts, poems friends and co-workers sent me because they thought these would resonate with me. The End of Poetry by Ada Limón is among them, and it takes my breath away every time I read it. It so perfectly captures my personal experience of this long moment.

In a different kind of way, Cady Noland’s poetic piece, The Big Slide, from 1989, caught my attention as I walked through the Art Institute’s galleries on my last day of work. It’s as if she took the myth of American omnipotence and dismantled it, revealing a new truth about who we are as a nation, one much more provisional and humble. Three decades later, this work seems as timely as ever.

Photo courtesy of Jacqueline Terrassa.

What is your favorite part of your house and why?

Definitely the big windows, or rather the view from them. I find myself starting out constantly. In fact, most of my Zoom meetings happen perched on the edge of the window on an improvised standing desk, looking towards sky and lake. The reality is that much of the view is of buildings, but in my mind it is of air and water. I will miss this view when I move in September. I will also miss my vintage parquet floor.

What’s your favorite work of art in the house and why?

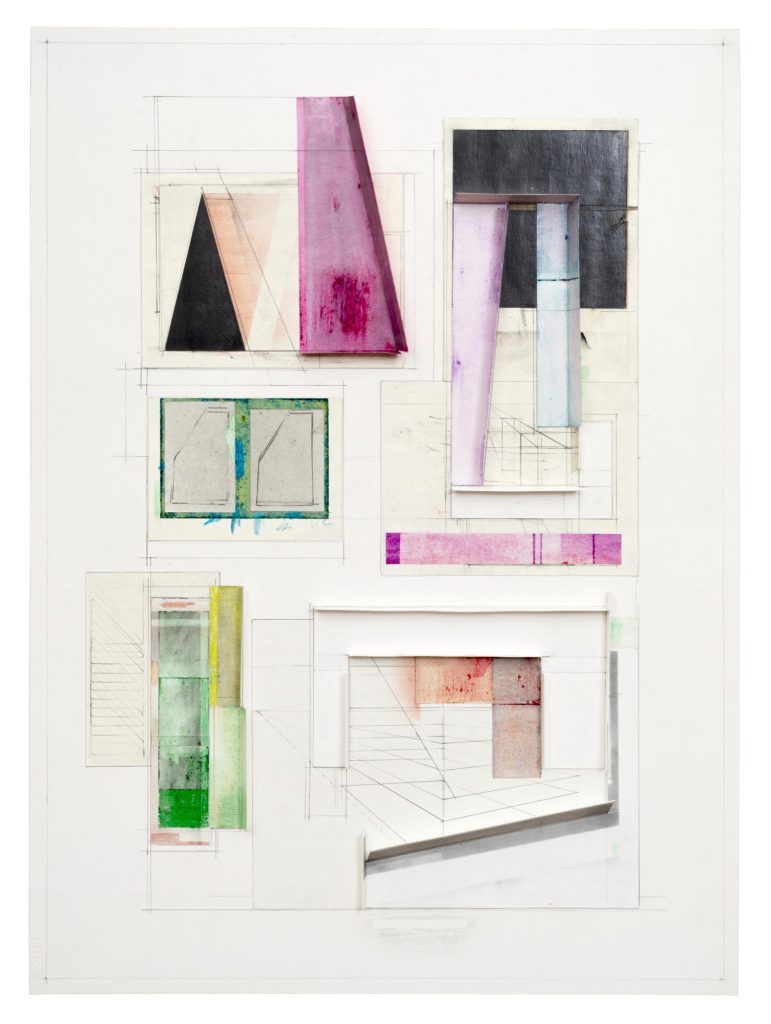

Tough one, as I have multiple favorites. They have come into my life at different points, often marking a transition. This one by the Chicago-based artist Deb Sokolow is the most recent. It’s called If Madame Blavatsky Had Been an Architect and it now seems auspicious given the shape of 2020. I purchased it in December. For me, it is all about thresholds that I envision myself crossing, and also about opening up spaces that don’t quite exist, about drawing provisional plans for other worlds.

Deb Sokolow’s If Madame Blavatsky Had Been an Architect (2019).

Are these any causes you support that you would like to share?

My main cause is education, which I have made central to the work I do. This fact is part of what appealed to me about leading an academic museum at this time, especially one with ambitious community engagement aspirations. I believe that, when oriented towards justice, processes of learning increase our sense of individual agency and our capacity for both collective responsibility and freedom.

The impact of positive learning experiences at an early age is well documented. This and the organization’s unique model led me to join the board of SkyArt, a great and small youth arts organization in the far South Side of Chicago that offers free, safe, holistic art spaces for kids to explore their creativity and make connections. The staff have been doing a remarkable job during the pandemic, distributing over 1,000 art kits to youth across their neighborhood, offering art-making sessions led by art therapists, and turning their garden and kitchen program into a produce distribution-plus-remote cooking lesson service.

What is your guilty pleasure?

Making a mock cortado either at dawn or mid-day, post-lunch. It involves heating a little evaporated milk, putting a little instant espresso and brown sugar in a favorite tacita, and then pouring in the just-boiled milk and stirring well. This small ritual reminds me of my mother and also of my grandfather. For her, it’s part of the start of each day. For him, coffee came after lunch. He would have lunch, have his instant coffee with milk, and then nap.

What’s going on in the kitchen these days? Any projects? Any triumphs or tragedies?

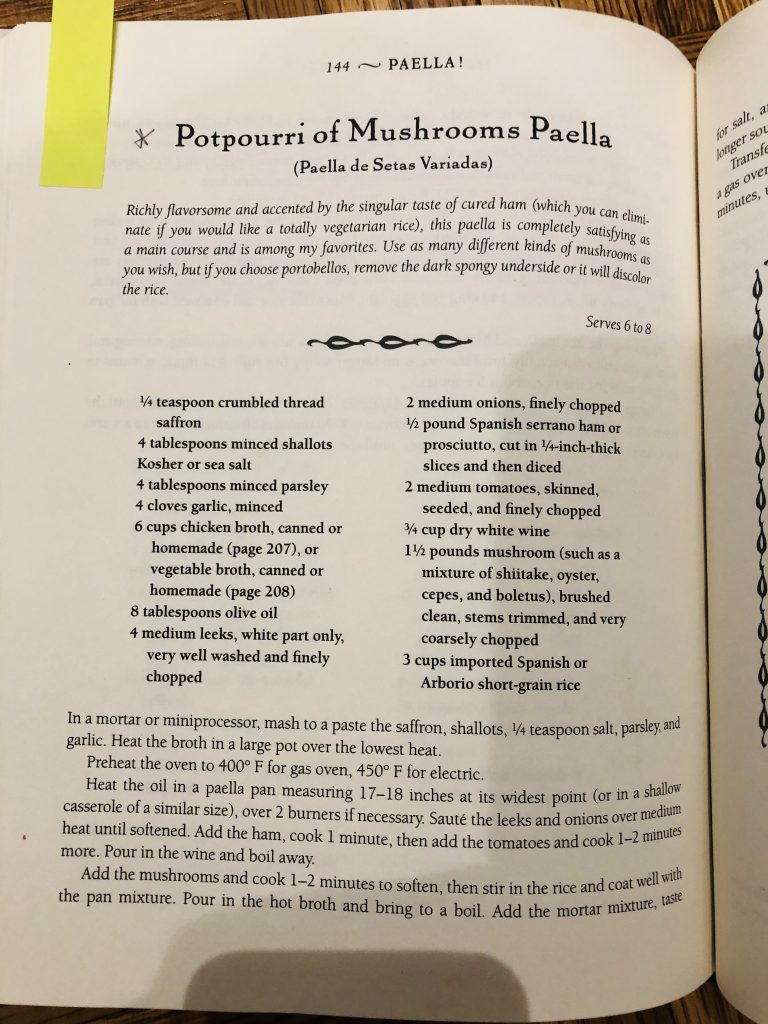

I love cooking for people. Obviously, that is not happening right now. And even though I live alone, I’ve done takeout exactly six times during the six months of this pandemic. Mostly, I’m preparing some simple fish, sautéing a large amount of something green, improvising with whatever produce I have, or making egg salad with toast and lettuce. My biggest accomplishment of these pandemic months has been making a delicious mushroom paella for a friend’s birthday in early June.

Photo courtesy of Jacqueline Terrassa.

Which two fellow art-world people, living or dead, would you like to convene for dinner, and why?

How fun it would be to have the writer and art collector Gertrude Stein and the scholar, composer, and musician George Lewis over for dinner? I would love to hear them talk about the politics and pleasures of experimental form and the social conditions of both composition and improvisation. All of this sounds deadly serious and heavy, but I bet they would lighten things up by laughing heartily, eating unabashedly, and telling great stories.

But Gertrude may not allow me to be the host, so I will propose another one: Raphael Montañez Ortiz and Noah Purifoy. Montañez Ortiz is a Nuyorican artist, educator, and founder of El Museo del Barrio. Purifoy’s amazing outdoor museum, filled with his assemblages, sits in the Mojave Desert on the north end of Joshua Tree. He was a founding director of the Watts Towers Art Center and also spent 11 years working for the California Arts Council on arts policy and programming.

Bonus: Where would you want the dinner to be?

We would definitely be outdoors, somewhere airy and unpretentious and maybe at the edge of a city. Maybe a park in Washington Heights in Manhattan or Griffith Park in LA. I would want to ask them about building institutions and working within them to shape policies of access and agency for the underclass, about being community educators while also being highly respected practicing artists, and about their artistic choices, including merging Duchampian, process-based, material, performative, and conceptual strategies as means for a highly poetic and socially engaged art.