On View

The Essentials: How to Understand Mark Bradford’s Evolving Approach to Art Through Four Stunning New Works

“Mark Bradford: You Don't Have to Tell Me Twice” is on view through July 28.

![Bradford studio, 2023.jpg; caption: “Imagination has always been something that has saved me. Imagination has been something I’ve always been able to escape to. When things outside were a little rough, imagination has always been a friend to me. I never thought I was an ‘artist’ but I did have an imagination.” -Mark Bradford] Bradford studio, 2023.jpg; caption: “Imagination has always been something that has saved me. Imagination has been something I’ve always been able to escape to. When things outside were a little rough, imagination has always been a friend to me. I never thought I was an ‘artist’ but I did have an imagination.” -Mark Bradford]](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2023/06/1-Photo_-Bradford-studio-2023-664x1024.jpg)

“Mark Bradford: You Don't Have to Tell Me Twice” is on view through July 28.

![Bradford studio, 2023.jpg; caption: “Imagination has always been something that has saved me. Imagination has been something I’ve always been able to escape to. When things outside were a little rough, imagination has always been a friend to me. I never thought I was an ‘artist’ but I did have an imagination.” -Mark Bradford] Bradford studio, 2023.jpg; caption: “Imagination has always been something that has saved me. Imagination has been something I’ve always been able to escape to. When things outside were a little rough, imagination has always been a friend to me. I never thought I was an ‘artist’ but I did have an imagination.” -Mark Bradford]](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2023/06/1-Photo_-Bradford-studio-2023-664x1024.jpg)

Gabé Hirschowitz

“Me saying hi to you is me welcoming you into the space and saying I see you, I see you,” said Mark Bradford to those gathered at the opening of his new exhibition “You Don’t Have to Tell Me Twice” at Hauser & Wirth’s 22nd Street gallery (on view through July 28). Bradford’s warmth hearkens back to his early days as a hairstylist, when he’d wave to every new customer to walk through the door.

Expressive and down to earth, the 61-year-old Bradford is known for such genuine moments of connection, even as his work has become canonical. In 2017, he represented the United States at the Venice Biennale, and in 2018, his painting Helter Skelter set a world record for the highest purchase price ever paid for a single work by a living African American artist, when it sold at auction for $12 million with fees. Now, the new “landscapes” unveiled at Hauser & Wirth underscore Bradford’s ongoing sense of experimentation, often offering a sense of revelation.

Installation view, “Mark Bradford. You Don’t Have to Tell Me Twice”; Hauser & Wirth New York 22nd Street, 13 April – 28 July 2023 © Mark Bradford; Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; Photo: Thomas Barratt

The exhibition at Hauser and Wirth is Bradford’s first solo exhibition in New York since 2015 and brings together works spanning from Bradford’s youth to his most recent creations and marks an important touchstone in his career. With that in mind, we’ve chosen what we consider to be 4 essential artworks in the exhibition that unlock insights into his larger practice, whether you’re familiar with Bradford’s work or you’re new to his practice. Read on to find out more.

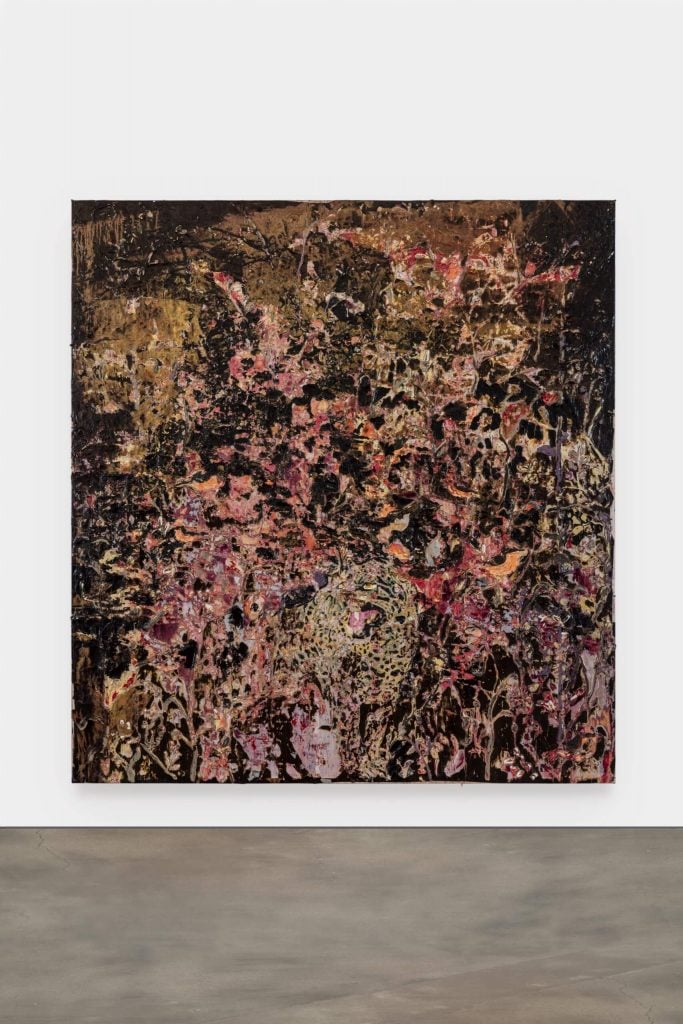

Mark Bradford, Johnny the Jaguar (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Hauser and Wirth. Photograph by Joshua White.

Just the Facts: The first floor of “You Don’t Have to Tell Me Twice” features a series of works that, according to Hauser & Wirth, are “informed by the history of European tapestry and their socio-political significance, as symbols of the greatest opulence of European aristocracy, and, by extension, their relationship to power.” Originally premiered at the Fundação de Serralves in Porto in late 2021, these works accompany more recent tapestry-like “landscapes” depicting flora and fauna indigenous to Blackdom–“an early-20th Century African American homesteader settlement in New Mexico.” Central to these tableaux is a “symbol of historical predation,” a large cat figure Bradford has fondly nicknamed, Johnny the Jaguar.

Insights: Bradford’s Johnny is very clearly a depiction of a Panthera Onca, the jaguar species indigenous to the Chihuahuan Desert of northern Mexico and the southern-western U.S., and as such is apt for its multiplicity of shifting significances: it might not only serve as a symbol for historical predation–recalling structures of power and race in America and Western colonialism more broadly–but as a symbol of the Aztec Empire’s elite jaguar warriors. And yet, even more intriguing, Panthera Onca is also today, in point of fact, an endangered species, perhaps pointing to a vision of oppression’s diminishment, if not end.

Mark Bradford, Fire Fire (2021). Photograph by Sarah Muehlbauer. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser and Wirth.

Just the Facts: The works featured at Hauser & Wirth New York mark a shift in Bradford’s work from his bird’s-eye views of cityscapes to eye-level allegories of “survival, violence, and desire.” The figure, according to Hauser & Wirth, was “the starting point of [Bradford’s] abstraction.” Reflecting on these works, the artist himself points out: “I really wanted to create these kinds of playful landscapes. … Maybe because there was so much pressure happening throughout Covid and through questioning who we are culturally and racially that I had to create sights within my own imagination to give myself permission to play and to move things around. I always have to create a sight to give myself permission to kinda f— things up.”

Insights: An immense work Fire Fire (2021) presents us with a drab and scabbed upper layer seemingly peeled away to reveal vibrant, colorful figures and shapes beneath., “I’m always thinking about how I can layer meaning, how I can create a visual metaphor, how I can be provocative in some way,” the artist said. In this case, it seems like the thrust of this layering is to reveal the new life hidden beneath the scars of catastrophe. “I’m interested in the kind of beauty that comes out of difficulty,” he explained “…I want my work to be a catalyst for conversations about social justice and equality.”

Several vibrantly colorful figures emerge from what seems the charred and blackened ashes of a vast and impersonally abstract conflagration: alongside deep teal, salmon, and cobalt blooms emerges the stylized depiction of a human arm gripping an upside-down jaguar by its tail. In the context of other works in the exhibition such as Jungle Jungle and Johnny the Jaguar, Fire Fire seems to betoken the hopefulness of deliverance from life’s spirited chaos and our resulting fears. And yet, it also brings with it terrors of its own, for it is a pale arm that grips the jaguar’s tale, implying that there may be more to fear than natural predation.

Mark Bradford, Death Drop 1973. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser and Wirth. Photograph by Sarah Muehlbauer.

Just the Facts: Central to the second floor of the show is a projector screen looping a Super 8 film Bradford directed at age 12. In it, Bradford’s adolescent self falls backward into a chain-link fence as he pretends to be struck by a bullet.

Insights: Bradford’s reflection on the film today is both inspiring and timely: “What’s important for me is that the kid wiggles back up. The falling is one side of it, but the fact he wiggled back up–that’s the journey.”

Mark Bradford, Death Drop 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser and Wirth. Photograph by Sarah Muehlbauer.

Just the Facts: “For me, art is about creating connections and building bridges between people,” Bradford has said. He also insinuates a connection between his younger self and his present person. A sculptural installation on the fifth floor titled, Death Drop 2023 in many ways references his childhood film Death Drop, 1973, in terms of considerations of violence and mortality.

Insights: The artist also connects his art and the exhibit to a wider context through the sculpture’s pose and title, a “death drop” being a popular pose in gay ballroom culture. Thus, pointing to the intersection of persecution and performance, the installation becomes both personal self-reflection and social commentary. This is to be expected from Bradford.”My work is always a response to what’s happening in the world. It’s always about the here and now,” he said.