Archaeology & History

A Priceless Amber Jewel, Beloved by Royals and Lost to Conflict

In this edition of "The Hunt:" The priceless chamber that stood for more than two decades in a royal palace. Then came World War II.

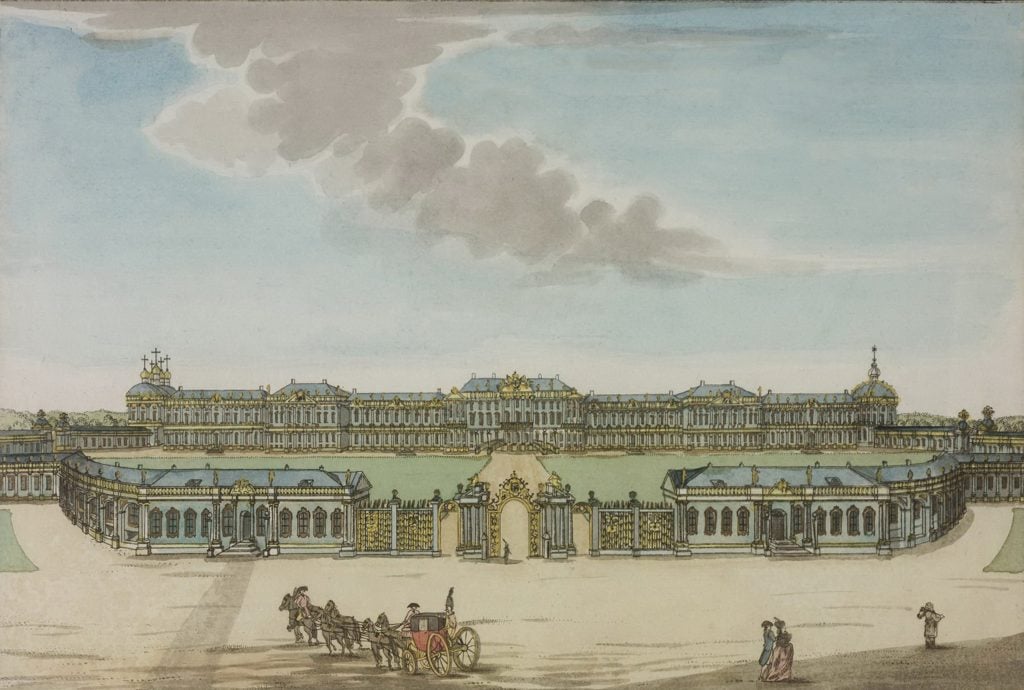

In the summer of 1941, Adolf Hitler loosed more than three million German troops on the Soviet Union. The invasion, part of Operation Barbossa, reduced cities to smoke, as soldiers emptied castles and museums from Kiev to Moldavia of their art and cultural heritage. Rumblings of their approach soon reached Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), home to the Hermitage Museum, Pavlovsk Palace, and Catherine Palace, which frantically began packing and hiding their contents.

While the Hermitage and Pavlovsk swiftly stowed objects and statues into crates lined with hay, the Catherine Palace was faced with a greater dilemma. Its furniture and ornaments could be packed up, but what of its Amber Room? The chamber was decorated throughout with ornate sheets of amber and gold leaf that were too delicate to disassemble. Despairing curators resorted to the next best thing: they hid the room’s walls behind drab wallpaper.

The Nazis saw right through the ploy. When the soldiers arrived at the palace in the town of Pushkin, they pried the amber panels off the walls, boxed them up into 27 crates, and sent them to Königsberg (now Kaliningrad) in east Germany. In 36 hours, the plunder was complete. For the first time in more than two centuries, Catherine Palace’s Amber Room stood bare.

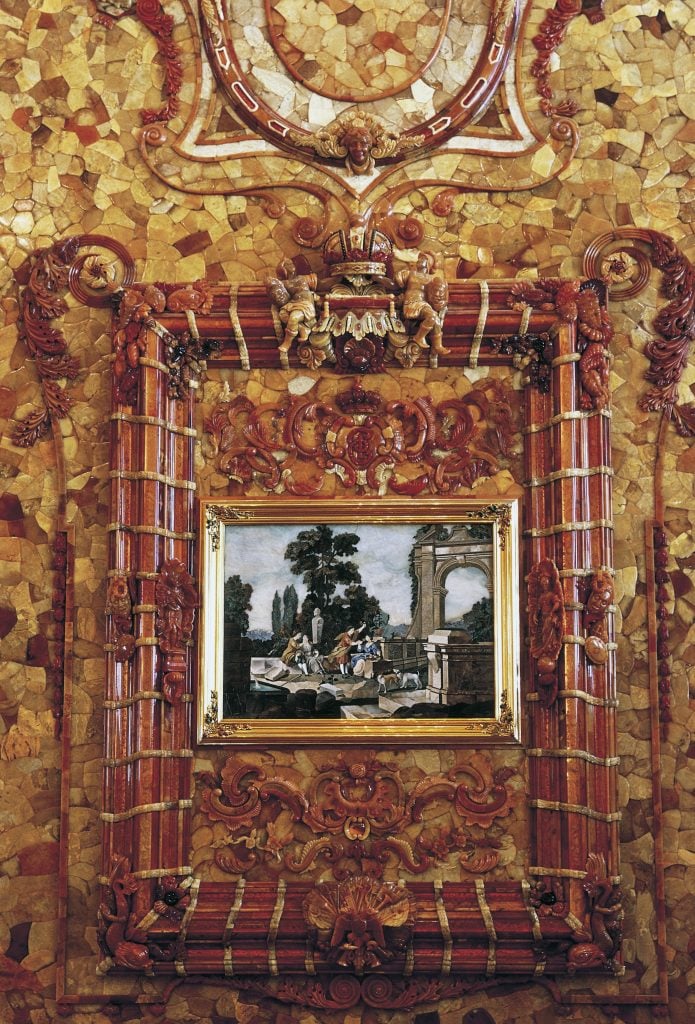

The Amber Room in Catherine Palace, Tsarskoye Selo, 1917. This is the only existing color photo of the room before World War ll. Photo: Sovfoto / Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

The famed Baroque room had its roots in 1696, when Frederick I, King of Prussia, and his second wife Sophie Charlotte, commissioned sculptor Andreas Schluter to redesign the interior of Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin. While rooting around in the palace’s cellar one day, he stumbled upon a hoard of amber, a valuable substance that had enriched its Eastern European traders for millennia past. The vast collection of amber in the royal cellar—the largest he had ever seen, he claimed—sparked in Schluter an idea to put it to opulent use.

Schluter devised a room decorated entirely with amber, the panels backed with gold leaf, intricately carved with nymphs and angels, and covered with mosaics and mirrors. Danish carver Gottfried Wolfram was summoned to craft the panels; he spent the next several years developing a technique for bonding amber into larger pieces. His team of amber masters produced about 46 panels, some measuring 12-feet high.

Sophie Charlotte Duchess of Brunswick and Lueneburg (1880). Photo: Bildagentur-online / Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Frederick and Sophie did not live to see their amber chamber; Schluter was unceremoniously dismissed following the deaths. By 1716, the panels were only partially installed in a room at the Berlin City Palace when Peter the Great paid a visit to then-king Frederick William I’s court. Peter admired the work and the Prussian ruler, no fan of amber, happily presented it to the Tsar as a diplomatic gift.

The panels were packed up and transported to St. Petersburg, but they still had a long way to go. Peter, not knowing what to do with the pieces, left them to molder in storage. In 1743, 20 years after his death, Tsarina Elizabeth had the amber panels assembled in Neva Enfilade of the Winter Palace at the discretion of sculptor Alexander Martelli. After moving them three more times, the empress finally had the pieces sent to her niece Catherine, who installed them at the Great Palace of Tsarskoye Selo (now part of Pushkin) in 1755.

The Catherine Palace in Tsarskoye Selo (1792–1820). Photo: Fine Art Images / Heritage Images / Getty Images.

During her reign, Catherine would add more gilded figures, precious stones, and mosaics to the panels, as well as an additional 900 pounds of amber. Her Amber Room would come to measure about 180 square-feet; it glowed golden in candlelight. In it, Elizabeth meditated, Alexander II arrayed his trophies in a corner, and the royal family had gatherings. It earned the title as the “eighth wonder of the world.”

“In the whole of world history, there has never been anything like this room,” amber restorer Alexander Krylov reflected in 1997. “The entire room was a gigantic piece of jewelry.”

After the Nazis looted the Amber Room, the jeweled artifacts were displayed in a room in Königsberg Castle—the last place they were ever exhibited. There, the panels remained until Allied forces arrived early in 1945. Hitler ordered all spoils in the Prussian city be transported away, but his administrators never got beyond packing up the Amber Room. Königsberg was leveled by the Royal Air Force, its historic castle destroyed and left to burn for days.

The Amber Room has not been seen since.

Though lost, the priceless treasure was not forgotten. Extensive hunts for the room, some by the Soviet Union, have been undertaken. Theories have abounded about its whereabouts—that it’s sitting in a secret bunker, under a lake, in a silver mine. Soviet officials have concluded that the Amber Room was lost to war.

The “Touch and Smell” mosaic in the recreation of the Amber Room in Catherine Palace, Pushkin, near St Petersburg, Russia, 2003. Photo: DeAgostini / Getty Images.

A close find, however, emerged in 1997: a stone mosaic that was once embedded in an amber panel, part of a cycle illustrating the five senses and presented by Maria Theresa of Austria. The marble and onyx “Touch and Smell” mosaic, as well as a lacquered chest, were discovered in the belongings of a German family, who had inherited them from a soldier known to send goods home from the Russian front. Experts who examined the relics concluded that they were likely stolen before the amber panels reached Königsberg.

Today, the mosaic and chest take pride of place in a full-scale recreation of the Amber Room in Catherine Palace. The reconstruction commenced in 1979, based assiduously on 86 black-and-white photographs taken of the original work, and concluded in 2003. Like its predecessor, the new, $11 million amber chamber is radiant with an orange glow, adorned with amber flourishes and Florentine mosaics recreated by amber craftspeople.

A block of rough amber next to a carved work for the recreation of the Amber Room. Photo: Patrick Aventurier / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

The new work might even beat the supposed state of its forebear. According to experts, the Amber Room was long in disrepair: “Even before it was stolen, it was in poor shape, in need of restoration, and the amber pieces were falling out,” specialist Alexander Shedrinsky told the New York Times in 2000.

And even if the original panels turned up today, they would be in remarkably different shape. “Amber is a complex material; it is quite fragile, and it changes over time,” Tatyana Suvorova, director of the Kaliningrad Regional Amber Museum, told the BBC in 2021. Finding the Amber Room would be “the greatest happiness,” she added, but “it would be a fact of history, not a work of art.”

The Hunt explores art and ancient relics that are—alas!—lost to time. From the Ark of the Covenant to Cleopatra’s tomb, these legendary treasures have long captured the imaginations of historians and archaeologists, even if they remain buried under layers of sand, stone, and history.