Archaeology & History

The Hunt: Genghis Khan’s Final Resting Place

Mongolia's first ruler asked to be buried in secret. He got his wish.

Mongolia's first ruler asked to be buried in secret. He got his wish.

Tim Brinkhof

Genghis Khan died in 1227 C.E. after having conquered a territory twice the size of the Roman Empire. His last wish was to be buried in secret, something his soldiers accomplished in two ways: by killing everyone they met en route to the gravesite, and then trampling that site under the hoofs of their horses until no trace was left. To this day, the location of the Khan’s final resting place—rumored to contain various treasures collected on his globe-spanning military campaigns—remains unknown.

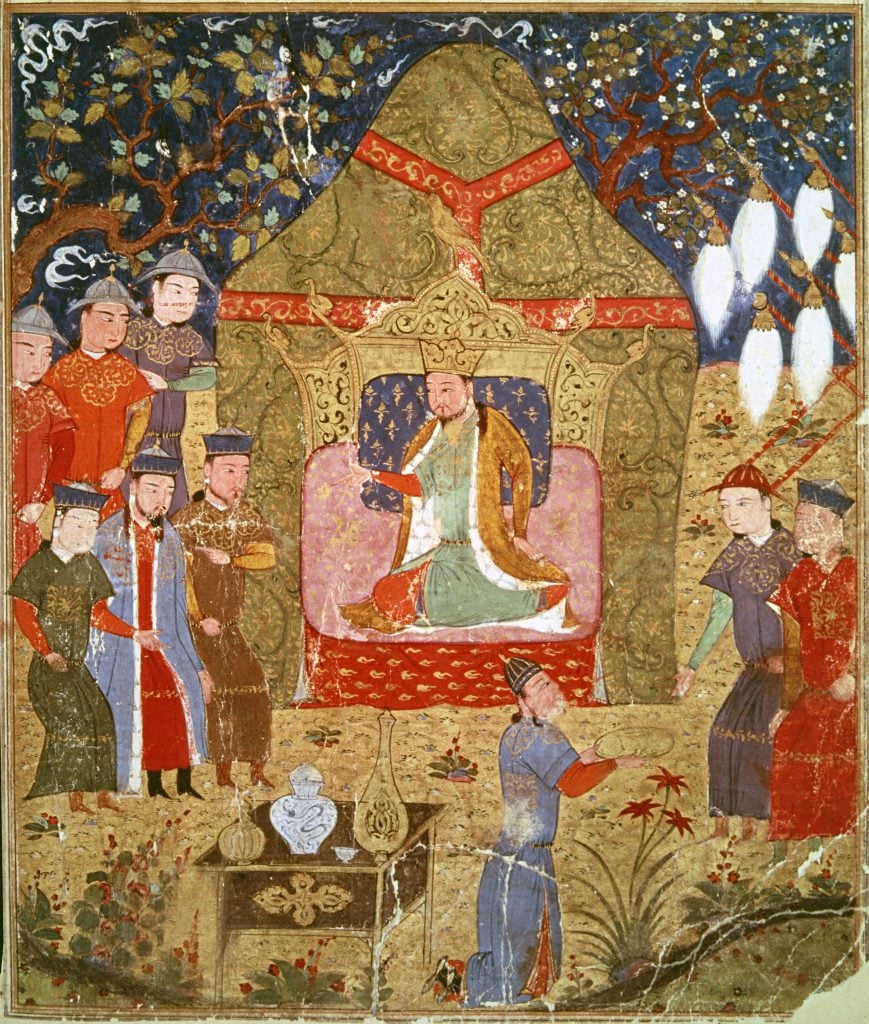

Detail from the Jami al-tawarikh (ca. 14th century) by Rashid Al-Din, depicting Genghis Khan proclaiming himself emperor. Photo: Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

The search for Genghis Khan’s fabled tomb poses numerous challenges. Mongolia is one of the biggest countries in the world, as well as the most sparsely populated. Roads cover less than two percent of its landmass, giving way to seemingly endless stretches of plains and deserts. In this situation, the phrase “needle in a haystack” isn’t hyperbole: it’s an understatement.

Local burial methods present additional complications. For much of their history, the Mongols simply left the dead where they had died, allowing their bodies to be consumed by animals and the elements. Although tomb culture, inherited from the neighboring Chinese, was well-established by the time Genghis Khan was born, many were constructed underground, some at a depth of more than 65 feet.

Some of these problems can be addressed with modern technology. National Geographic’s Valley of the Khans Project, which has been ongoing since 2011, uses non-invasive digital imaging, aerial photography, and radar to locate the tomb.

Genghis Khan statue, designed by sculptor D. Erdenebileg and architect J. Enkhjargal, in Tsonjin Boldog near Ulan Baator and Erdenet in Mongolia. Photo: Joel Saget / AFP via Getty Images.

A more conventional expedition took place in the 1980s. Led by Head of the Department of Archeology at Ulaanbaatar State University Diimaajav Erdenebaatar, it concentrated on Genghis Khan’s birthplace in Khentii Province. Despite the optimism of those involved, the expedition was shut down in 1990, when the Mongolian Democratic Revolution, which saw the country separate itself from Communist Russia, led to a wave of protests.

Protests against the expedition, that is. As journalist Erin Craig explained in an article for the BBC, most Mongolians today would prefer if Genghis Khan’s tomb stayed hidden. Not because discovering it would unleash an ancient curse—a superstition that was actually quite widespread in Soviet times—but simply out of respect for the historical figure’s dying wish. “Mongolia,” Craig summarized, “is a country of long traditions.”

White horsetail banner of Genghis Khan, seen at a festival in his native Khentii Province, Mongolia, 1997. Photo: Richard Manning/Getty Images.

Many archaeologists and historians now believe the tomb may be located on Burkhan Khaldun, a peak in the Khentii Mountains north of Ulaanbaatar where Genghis Khan hid from his enemies as a young man and pledged to return after he died, according to some sources. Unfortunately for these experts, the peak falls under a protected wildlife conservation area that the Mongolian government does not permit anyone to enter for any reason, whether spiritual or scientific.

Perhaps the closest anyone has come to finding the tomb of Genghis Khan was in 2015, when French archaeologist Pierre-Henri Giscard and imaging expert Raphaël Hautefort employed drones to scout Burkhan Khaldun’s summit. Although they reportedly came across a manmade tumulus, there is currently no way of learning what—if anything—awaits inside.

The Hunt explores art and ancient relics that are—alas!—lost to time. From the Ark of the Covenant to Cleopatra’s tomb, these legendary treasures have long captured the imaginations of historians and archaeologists, even if they remain buried under layers of sand, stone, and history.