Archaeology & History

Were the Hanging Gardens of Babylon Ever in… Babylon?

This edition of "The Hunt" delves into the sole Seven Wonder of the Ancient World without a definitive location.

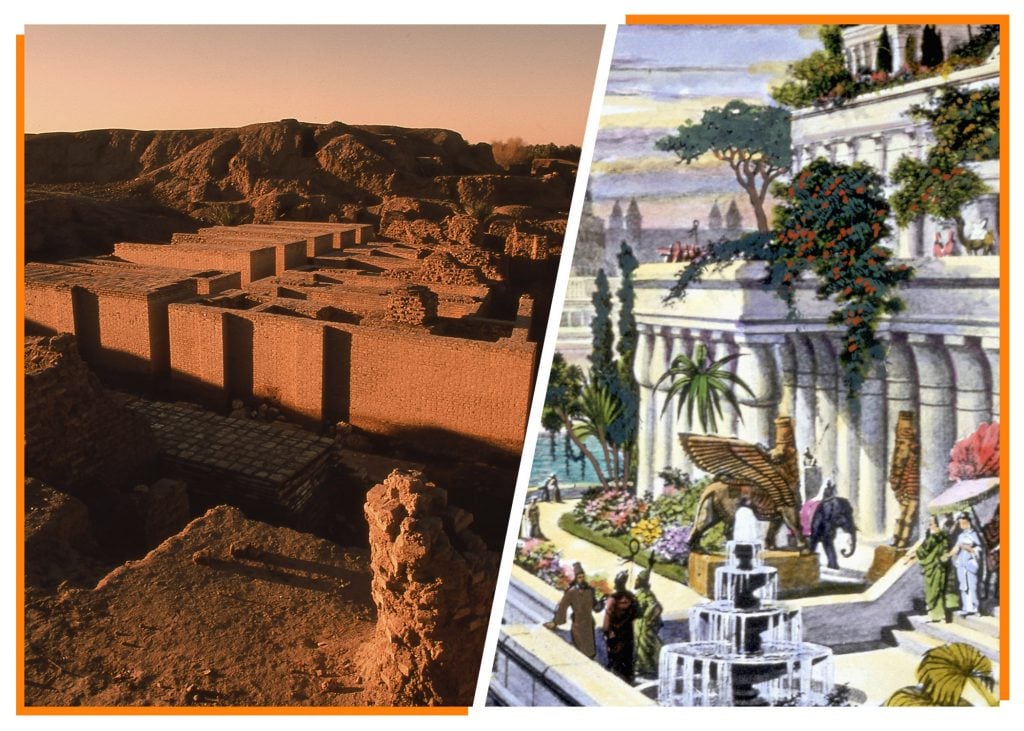

Visualizing the greatest metropolis in the ancient world requires the full powers of imagination. This is partly due to simple geology. The sun-hardened mud bricks favored by Babylon’s builders have stood up poorly to four millennia of rain, wind, and earthquake. Humans, too, have played a role. First came the colonial archaeologists who carted off city’s treasures westward. Later, British railways, ham-fisted restoration efforts, and a U.S. military base damaged the site further.

Today, the capital of the Babylonian empire 50 miles south of Bagdad is a vast expanse of heavily eroded structures interspersed with modern reconstructions. Despite its fame, UNESCO recognition only arrived in 2019 and its best-known monument, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, is nowhere to be seen.

A view over the ancient city of Babylon. Photo by Nik Wheeler/Corbis via Getty Images.

It’s the most enigmatic of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, one first extolled by the Hellenic historians. The earliest textual evidence comes from Berosus, a 3rd-century B.C.E local priest, keen on informing his upstart Greek overlords of Babylon’s culture and history—Alexander the Great conquered, rebuilt, and presided over Babylon before promptly dying within its sumptuous palace in 323 B.C.E.

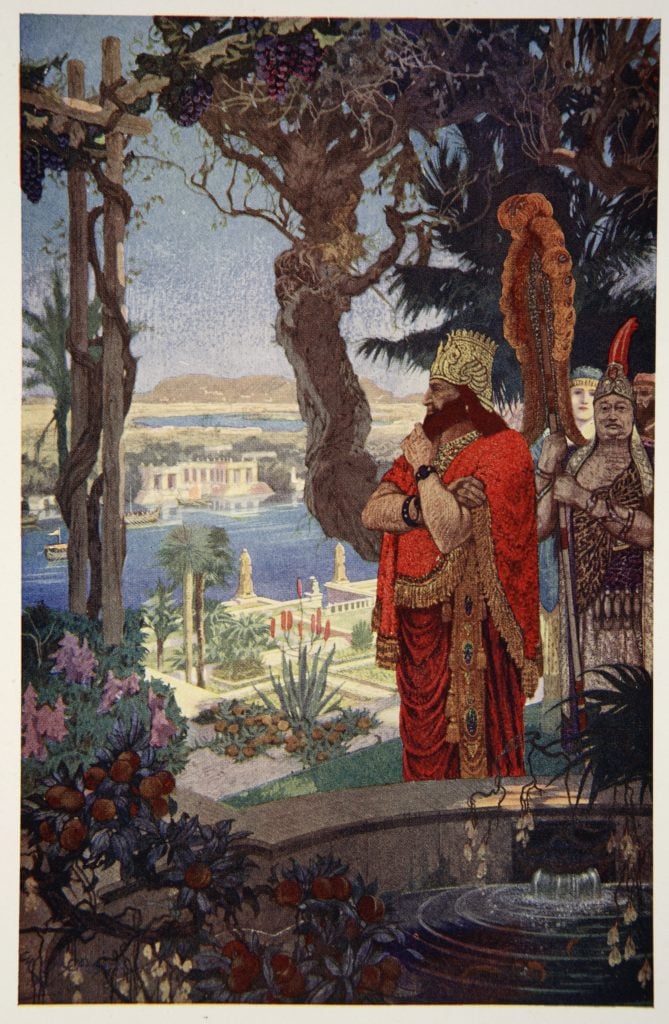

Berosus looked back two centuries to the reign of Nebuchadnezzar, under whom the Babylonian empire reached its zenith. After building a new palace and expanding the city’s walls (a task that allegedly took 15 days and is also considered a wonder of the ancient world), the king embarked on a more personal project. His wife Amytis was homesick for the lush mountains of her native Media, an area by the southern Caspian Sea in modern-day Iran, and so he gifted her a paradise emulating its extravagant flora.

Nebuchadnezzar in the Hanging Gardens Of Babylon, from Myths of Babylonia and Assyria by Donald A. Mackenzie (1915). Photo: © Historical Picture Archive/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images.

Neither the exact form nor location of Amytis’s garden is offered. To complicate matters, Berosus’s original writings have disappeared and exist only as quotations in the work of later scholars. Greek historians writing in the first century B.C.E offer more detail, though the extent to which they can be trusted remains debated.

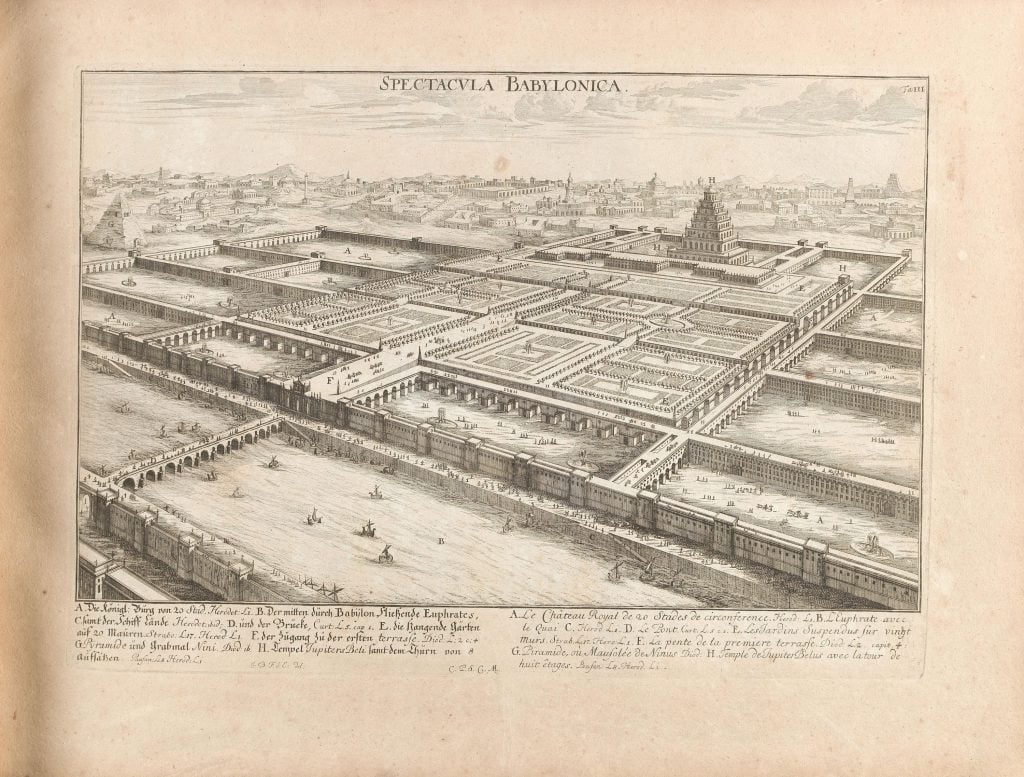

Strabo, the Greek scholar known for his encyclopaedic work Geography, described a four-sided garden with terraces raised up by brick and asphalt arches high enough to accommodate the largest of trees. The higher terraces, he wrote, were reached via a stairway that ran parallel to a mechanism that conducted water uphill from the Euphrates river.

An artist’s impression of Ancient Babylon with its gardens made in Germany in the early 18th century. Photo: Getty Images.

Diodorus Siculus goes further, providing precise measurements: 100 feet long, 100 feet wide, and 75 feet high — thereby level with the city walls. He wrote that water was prevented from permeating the roofs through a layering of reeds, tar, bricks, and lead and that the complex was irrigated by way of channels and pumps. All the same, modern scholars contest whether these descriptions propose a tight grouping of rooftop gardens or a series of terraces.

Locating the site of these luxurious royal gardens has bewitched archaeologists. The chief problem is that a complex formed of mud and vegetable does not endure, which poses the question: what exactly should archaeologists be looking for?

A 3D model of Babylon created by Babylon scholar. Olof Pedersén. Photo: Olof Pedersén.

In 1899, German archaeologist Robert Koldewey discovered an unusual structure in the southern part of the city: a large room with chambers and a vault. Could this, he speculated, have been a well from which water was raised to elevated gardens?

This site, however, far from both the private quarters of the palace and the river seems hardly ideal. The administrative records found on site also point to an alternate use. Others have proposed that the gardens were located outside of the palace beside the river. But the leading theory, one recently proposed by Olaf Pedersén, is that it was located on a west facing terrace of Nebuchadnezzar’s North Palace.

An Assyrian wall relief showing gardens in Nineveh. Photo: Biblical Archeology Society.

After two centuries of archaeologists scouring Babylon’s four-square-miles for proof of the wonder, Assyriologist Stephanie Dalley posed a bombshell conjecture: the gardens were, in fact, Assyrian and built 300 miles away in Nineveh by Sennacherib. For proof, Dalley pointed an inscription that read, “Over a great distance, I [Sennacherib] had a watercourse directed to the environs of Nineveh.” This is backed up by evidence of a complex system of canals, dams, and aqueducts that transported water from the Zagros Mountains.

With excavations at Nineveh back under way following years of regional conflict, the truth about Mesopotamia’s mercurial gardens may yet emerge.

The Hunt explores art and ancient relics that are—alas!—lost to time. From the Ark of the Covenant to Cleopatra’s tomb, these legendary treasures have long captured the imaginations of historians and archaeologists, even if they remain buried under layers of sand, stone, and history.