Archaeology & History

The Hunt: Are the ‘Peking Man’ Fossils Buried Beneath a Parking Lot?

Uncovered in China in the 1920s, the ancient human fossils went missing during World War II.

Uncovered in China in the 1920s, the ancient human fossils went missing during World War II.

Adnan Qiblawi

When the “Peking Man” fossils went missing during World War II, the loss was considered one of the greatest tragedies in the history of paleoanthropology. After almost 80 years of searching, scientists may have finally tracked the fossils to a footlocker buried beneath a parking lot in China.

In the 1920s, a team of paleontologists were working in the Zhoukoudian caves, 30 miles southwest of Beijing (Peking is the previous romanization of that city’s name). The area was known to the locals as Dragon Bone Hill, named after the bones commonly found jutting out of the ground. Though most of the fossils dug up by the scientists came from animals, the paleontologists came to amass a collection of 200 bones belonging to men, women, and children of a species of primitive humans—the first-ever discovery of ancient human bones on mainland Asia. The collection of bones came to be called the Peking Man fossils.

(Original Caption) Anthropologists and local workmen dig near the original cave where the Peking Man skull was discovered, 1980. Photo: Bettmann / Contributor.

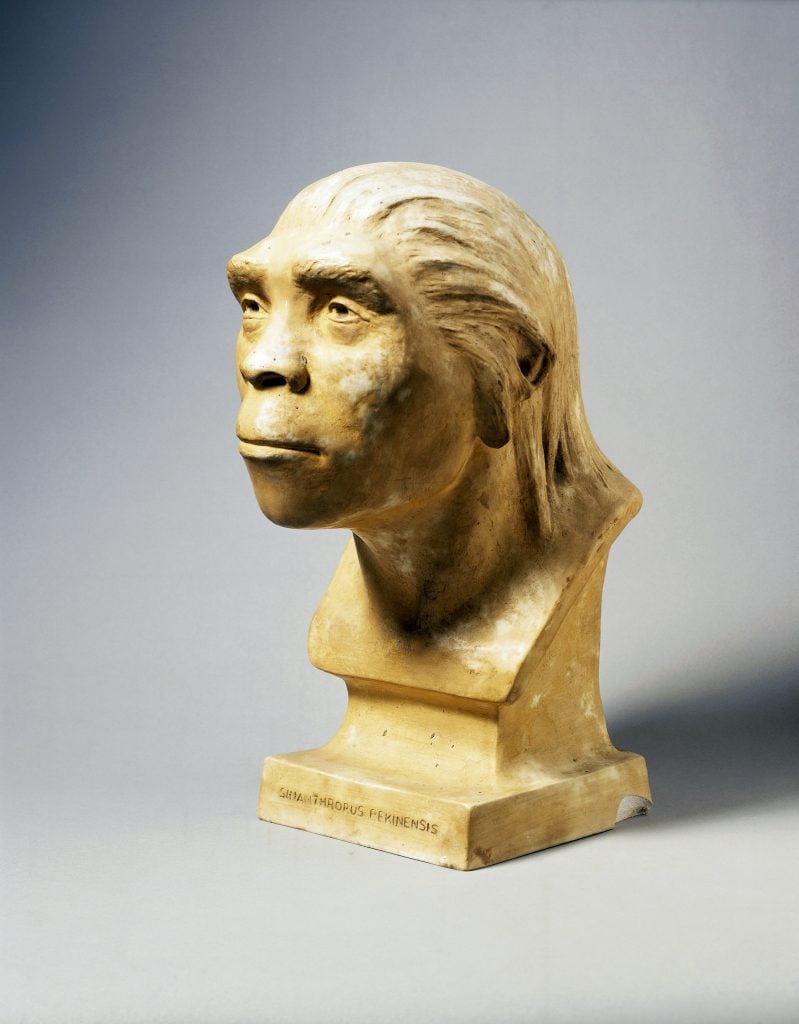

A Canadian anthropologist, Davidson Black, believed the Chinese fossils might represent a new and distinct species of hominid: Sinanthropus Pekinensis. The bones were found in astronomically rare, well-preserved conditions amid sophisticated stone tools like axes and hammers. The caves also showed signs of controlled fire use, meaning the protohumans who inhabited them likely lived in tight communities, and hunted and cooked their food. The discovery’s potential to redefine the known history of humanity was enormous.

In 1941, in the face of an imminent full-scale Japanese invasion of China, American archaeologists reluctantly agreed to smuggle the fossils to the United States for safekeeping, since they knew from experience that imperial invaders tended to loot the cultural treasures of the people they conquered. First, they beseeched the American ambassador to China for help, but he refused to take the bones out in his luggage. Eventually, the scientists turned to the U.S. military. They made plaster casts of the bones, which they smuggled out as soon as they could. Next, they packed the bones in cotton and stuffed them in two military lockers. These lockers were passed off between U.S. bases until they landed at the Camp Holcomb coastal military base in Qinhuangdao.

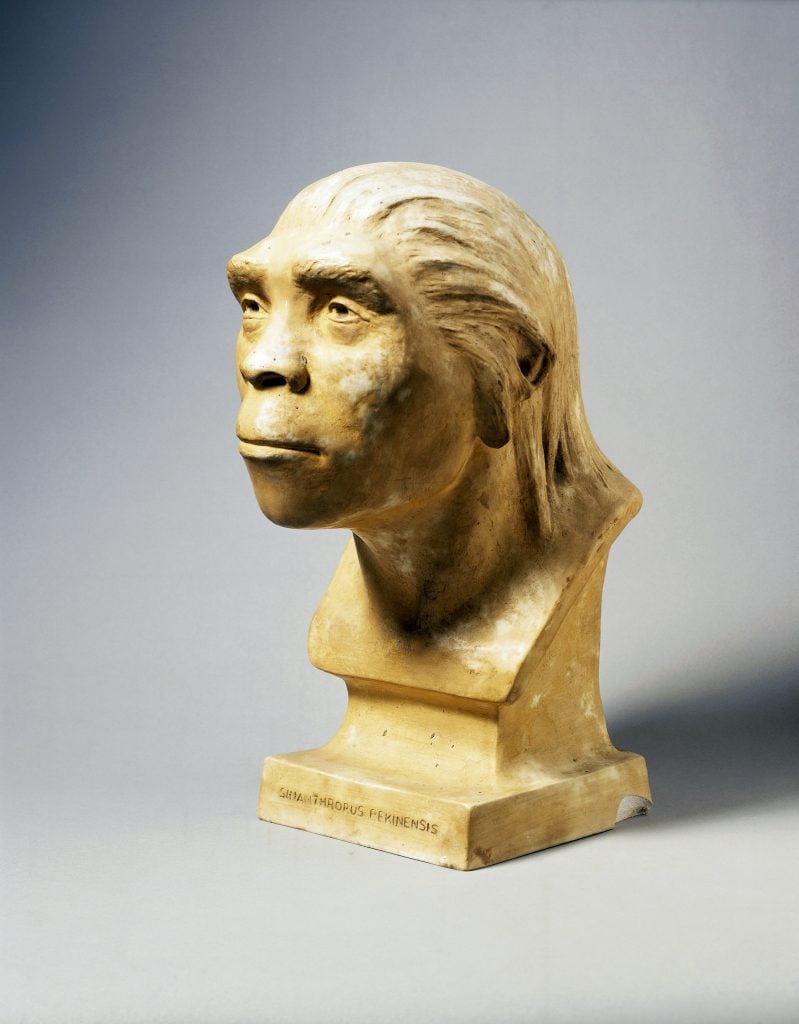

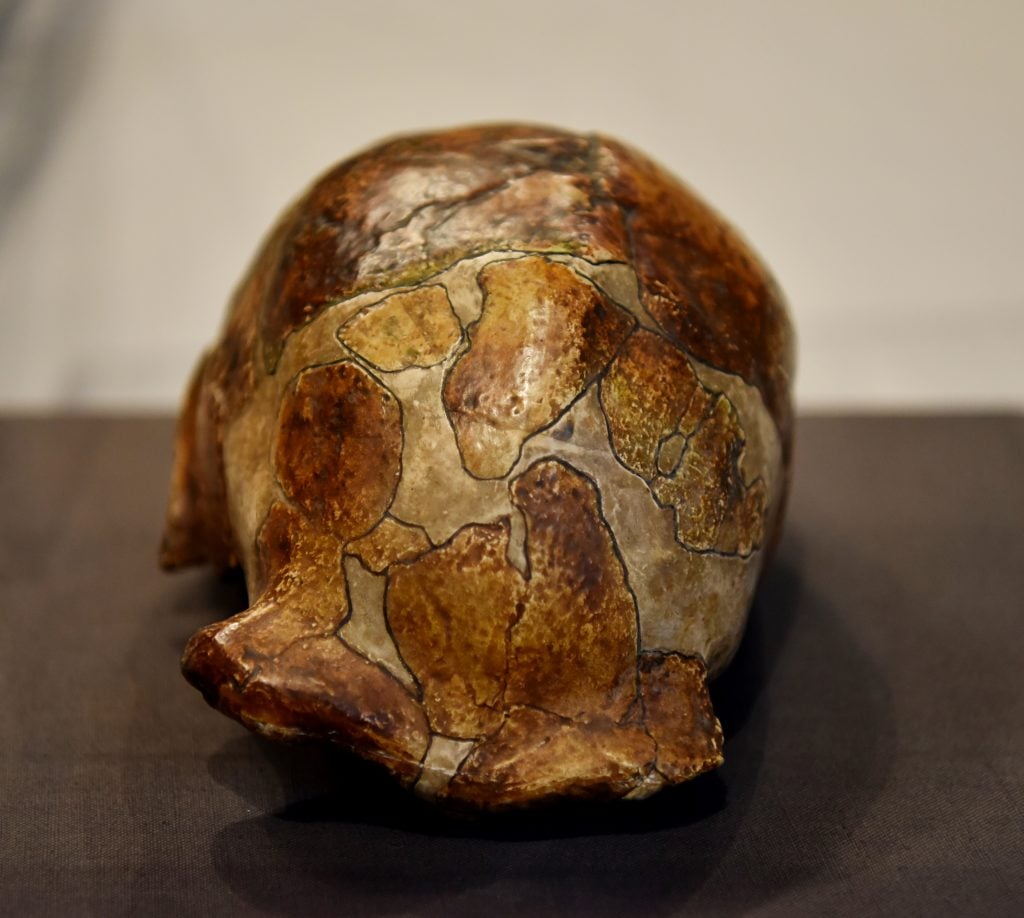

The fossilized skull of the Peking Man at Zhoukoudian Peking Man Site Museum, Fangshan District, Beijing, China, 2023. Photo: CFOTO / Future Publishing via Getty Images.

As predicted, Japanese scientists soon raided the lab where they believed the fossils were being kept. They were enraged to find the bones missing. An American lab associate was held and interrogated for five days about the fossils’ whereabouts, but the lockers had been lost to the havoc of war.

Scientists never stopped looking for the missing fossils. One, in his desperation, even relied on the expertise of a professional psychic who had previously used a dowsing rod to find Bigfoot in Maine. One rumor claimed that marines at Camp Holcomb buried the footlockers in the ground for safekeeping. Others claimed the Japanese found the bones and tossed them out with the trash. The FBI and the CIA got involved with checking leads, sifting through scammers who claimed to have the fossils and asked for million-dollar ransoms.

Cave at the Peking Man site at Zhoukoudian, China. Photo: DeAgostini/Getty Images.

After decades of nothing but dead ends, the case caught a break in 2010, when the son of a former U.S. marine emailed paleontologists at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa. He claimed his father, Richard Bowen, had accidentally uncovered a chest of bones while he was stationed at a U.S. military base in China during its civil war in 1947. The marine told the scientists the story of how his shovel collided with the locker full of bones when he was digging a foxhole in the face of an invasion by Chinese Communists at the military base. The scientists consulted military records and found that the details checked out.

A few months after receiving the email, the scientists traveled to the port city of Qinhuangdao with their fingers crossed. They arrived at the former location of Camp Holcomb to find an industrial area of warehouses, and a parking lot where the footlocker was reportedly buried. The scientists could do nothing to retrieve the trove of fossils. Supposedly, the area is slated for redevelopment in the near future, which might allow for an excavation of the site.

The Peking Man fossils survived for millennia in the Zhoukoudian caves and multiple modern military incursions. Their very fossilization is an incredible rarity, let alone their survival, discovery by archaeologists, and rediscovery by a U.S. marine. With those odds, perhaps they endured the construction of industrial Qinhuangdo and may yet one day be rediscovered.

The Hunt explores art and ancient relics that are—alas!—lost to time. From the Ark of the Covenant to Cleopatra’s tomb, these legendary treasures have long captured the imaginations of historians and archaeologists, even if they remain buried under layers of sand, stone, and history.