On View

The Secret Lives of Henry VIII’s Wives Revealed in 6 Objects

"Six Lives" at the National Portrait Gallery offers rare insight into the women who defined the legacy of one of Britain's most notorious kings.

We know about their husband, King Henry VIII, and we know the fates they suffered: divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded, survived. But how much do we actually know about each of these six wives—Katharine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, Jane Seymour, Anne of Cleves, Katherine Howard, and Katherine Parr—who, in fairly quick succession, became Queen of England?

A new exhibition, “Six Lives” at the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in London, centers this troupe of Tudor women in a new account of their lives and enduring legends. Each woman has a dedicated gallery to tell her story through books, tapestries, and other public documentation, as well as personal possessions like jewelry, private letters, and playing cards.

These precious archival objects offer intriguing insights into ruthless Tudor politics and the court’s cruel rumor mill. The drama of these historical happenings could hardly be heightened, as various troublesome men called Thomas—including Cromwell, Howard, Cramner, and Wyatt – used Henry’s six wives as pawns in never-ending power plays.

Installation view of “Six Lives: The Stories of Henry VIII’s Queens” at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Photo: © David Parry.

Other galleries reveal how Henry’s six wives have captured the imagination over many generations, whether via campy black-and-white film or hit West End musical, postage stamps or Christmas tree decorations. Through the centuries, these endless homages have put us at a greater remove from the wives, transforming them into vessels for each era’s projections about women.

Among the highlights of the contemporary interpretations are Hiroshi Sugimoto’s eerily lifelike photographic portraits of the six wives’ wax figures at Madame Tussauds in London. Though we can’t be sure of their likenesses, this series reminds us that these highly mythologized historical figures were actually people, and provides a nice counterpoint to the towering royal portrait of Henry himself, an archetypal image of patriarchal power. Here are six objects in the show that reveal something about the real women behind the myth.

Katherine of Aragon

Katherine of Aragon (c. 1520) by an unknown artist. Photo: © National Portrait Gallery, London, by permission of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Church Commissioners; on loan to the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Though Katherine of Aragon had some English ancestry, she was born Catalina de Castilla y Aragón and raised in Spain. She originally married Henry’s older brother Arthur but, after his sudden death, had little choice but to settle for the spare who was barely 18 to her 24 years. Sadly, her only child to survive infancy was Mary, a daughter born on February 18, 1516, who would later go on to become Queen Mary I—colloquially known as “Bloody Mary” for her violent attempts to overturn the Protestant Reformation during her reign.

During his marriage to Katherine, Henry became increasingly dissatisfied with the lack of a male heir. In 1525, when Katherine was 40, her younger lady-in-waiting Anne Boleyn caught Henry’s eye and he set about plotting to end their marriage. Notoriously, this led to a major clash with the Pope and the king’s battle to secure an annulment was dragged out for years before it was finalized in 1533. Katherine died three years later.

16th century music manuscripts from Petrus Alamire’s workshop in Bourg en Bresse, France. Photo: Godong/ Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

One object on display at the NPG speaks to the worry and tragedy that plagued Katherine’s childbearing years. Possibly a gift from Margaret of Austria, the illuminated choir book by the scribe Petrus Alamire contains a motet “Celeste beneficium,” calling on the patron saint of pregnancy, St. Anne, as well as a lament by King David in mourning for his late son Absalom. It is also decorated with the English royal arms and the letters “H” and “K.”

Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (late 16th century, based on a work of ca. 1533–6) by an unknown English artist. Photo: © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Perhaps the most memorable of Henry’s six wives, Anne Boleyn was courted by the king for years as the paramours had no choice but to wait for him to find a way to end his first marriage. Have any of your lovers ever broken with the Catholic Church and decided to head their own, forever changing the course of their nation’s history, just to be with you? Ladies, if he wanted to, he would.

Once the seven-year wait was over, Boleyn’s coronation had to be pretty quick because she was already five months pregnant. Her daughter, the future Queen Elizabeth I, was born on September 7, 1533. Unfortunately, it wasn’t long before she fell out with Thomas Cromwell over how to deal with the country’s defunct monasteries and he engineered the necessary circumstances to have her arrested for adultery, whipping up Henry’s imagination with unfounded court whispers. She was found guilty in a carefully stage-managed trial and executed by public beheading.

Anne Boleyn’s “Book of Hours.” L: Psalms of the Passion with inscription by Henry VIII. R: The Annunciation with inscription by Anne Boleyn. Photo courtesy of the British Library Archive.

Boleyn’s “Book of Hours,” on view in “Six Lives,” is a personal prayer book that she used to communicate with Henry during their clandestine dating phase. Under an image of Christ as the Man of Sorrows, he has written: “If you remember my love in your prayers as strongly as I adore you, I shall hardly be forgotten, for I am yours. Henry R. forever.” A promise that would prove to be false when he ordered her death. She responded under an image of the Annunciation: “By daily proof you shall me find / To be to you both loving and kind.” Her signature was later trimmed from the page, perhaps in an attempt to erase her from history.

Jane Seymour

Jane Seymour (ca. 1537) after Hans Holbein the Younger. Photo: © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Due to her brief reign and, it seems, intentionally self-effacing approach to her public image, there are limited records of Jane Seymour. Henry wasted no time in courting her while Anne Boleyn was still awaiting execution in the Tower of London and they were married within just two weeks of his ex’s death. Pressure mounted for Seymour to provide Henry with a male heir after parliament passed the Second Act of Succession, which removed Elizabeth and Mary from the line to the throne. Just three days after the birth of her son Edward on October 12, 1537, Seymour was up and greeting attendees outside his Christening, but just a few days later she fell ill and died on October 24.

Hans Holbein the Younger pendant designs featuring penitent Mary Magdalene. Photo courtesy of Kunstmuseum Basel.

Drawn pendant designs by Hans Holbein the Younger featuring the penitent Mary Magdalene are on view at the NPG. A similar scene was recorded in the plan for a pageant held on the day Seymour was proclaimed queen, and was headed by her motto “Bound to Obey and Serve.” It might be interpreted as reflecting the faithful and passive role that the devout queen intended to play during her short reign.

Anne of Cleves

Anne of Cleves (1539) by Hans Holbein the Younger. Photo: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Henry’s second foreign bride, Anne of Cleves hailed from… Cleves, a small state in modern-day Germany. If you think assessing looks by photos on Hinge is hard, spare a thought for Henry in his international search for a new wife to replace Jane Seymour. To help him visualize the options, he sent Hans Holbein the Younger on a trip around Western Europe to paint potential matches. Eventually, under some duress to choose, Henry picked Anne based on her picture. When their first meeting was a disaster, with Henry taking on the guise of a chivalric knight and Anne lacking a sufficient grasp of English to respond in good humor, it was too late to immediately back out.

Henry found himself unable to consummate the marriage and it only took him six months to find grounds for annulment, resorting to the age-old trick of questioning her virginity. This time, the divorce was amicable and Henry gave Anne generous provisions and continued royal status on the condition that she remain suitably “quiet and merry.”

Queen of Hearts playing card (late 16th century) by an unknown artist Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Traveling from Cleves to an unknown new life in England at the age of 24, Anne was forced to spend two weeks waiting in Calais before crossing the English Channel due to bad weather. In an attempt to prepare for court life, she asked her escort Lord High Admiral, Thomas Wriothesley, to teach her one of the king’s favorite card games. A trio of late 16th-century cards in the Paris pattern are on display in “Six Lives,” providing an example of the kind of deck she might have played with.

Katherine Howard

Probably Katherine Howard (ca. 1540) by Hans Holbein the Younger. Photo: © The Buccleuch Chattels Trust.

Katherine Howard’s particularly brief reign from July 1540 until November 1541 is most notable for how easily she managed to steal Henry’s attention away from Anne of Cleves while serving as her maid of honor. Immediately after she married him, she was showered with gifts originally intended for Anne but few materials have survived that specifically bear her name or initials.

Katherine’s downfall is better documented, however, which came swiftly after pious Thomas Cramner filled Henry in on the gossip about some of her alleged earlier dalliances, greatly shocking the besotted king. One of these was with music teacher Henry Manox, who took advantage of Howard when she was just 13, and the other a relationship with courtier Francis Dereham. In a desperate attempt to evade scrutiny, Dereham exposed a potential extramarital affair with the courtier Thomas Culpeper. In the end, Dereham, Culpeper, and Howard were all executed for treason.

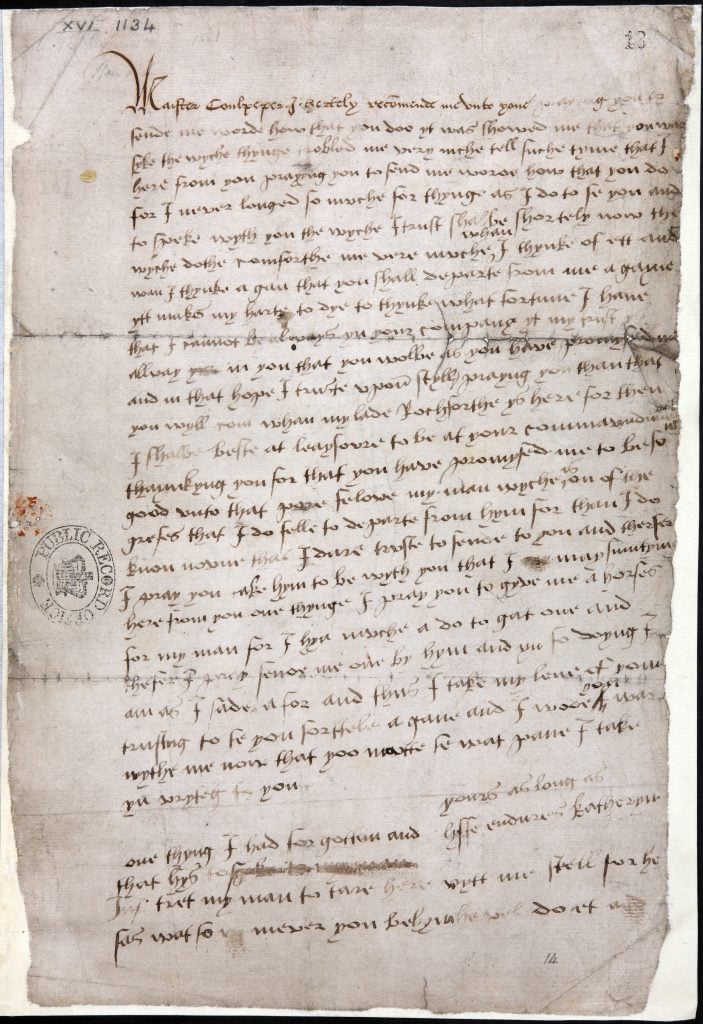

Letter from Katherine Howard to Thomas Culpeper from 1541. Photo courtesy of The National Archives.

One letter written in 1541 from Howard to Culpeper is included in the show at the NPG. It is signed “yours as long as life endures, Katheryn.” It was used as evidence against her.

Katherine Parr

Katherine Parr (ca. 1547) attributed to Master John. Photo: Fraser Marr, © Private Collection, London.

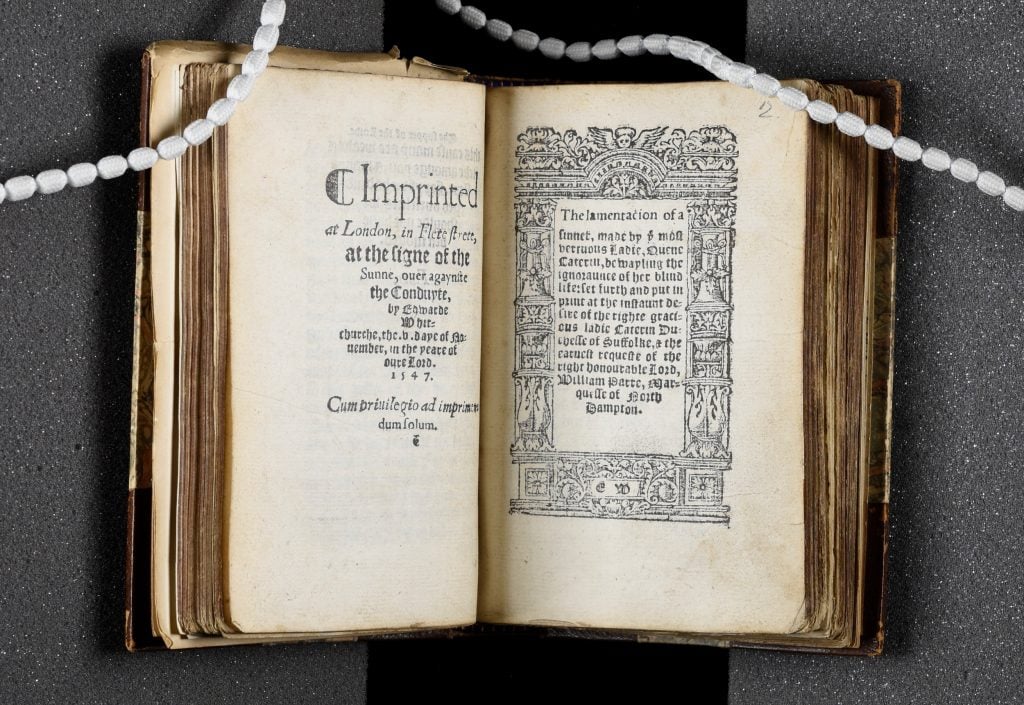

Aside from outliving Henry and putting an end to the curse that seemingly followed his courtship, Katherine Parr was a tour de force. She was not only a keen patron of the arts but a writer and the first English queen to publish under her own name with Prayers and Meditations (1545), which included five original prayers.

This was followed up by The Lamentation of a Sinner (1547), a boldly self-reflective enquiry into themes of sin, repentance, and the Lutheran concept of justification by faith alone. The copy on display at the NPG is small, revealing it as a book intended for private reading. Beside it is a copy of Parr’s first book Psalms or Prayers Taken out of Scripture, published anonymously in 1544. It carries an inscription written by Henry on the back of the title page.

Katherine Parr’s Lamentations of a Sinner (1547). Photo: By permission of the Master and Fellows of Pembroke College, Cambridge.

At court, Parr forged a close bond with her stepchildren and was influential in passing the Third Succession Act, restoring Mary and Elizabeth to the line of succession to the throne. She later had them sent to Hampton Court to be educated alongside their half-brother Prince Edward, passing the baton on to the next generation of England’s Queens.