Art & Exhibitions

The Zero Group Scores a Big Goose Egg at the Guggenheim

Once futuristic, this work now belongs in the dustbin of art history.

Once futuristic, this work now belongs in the dustbin of art history.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

The Guggenheim’s “ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s–60s” is the first large-scale US survey dedicated to the group Zero, the latest European boys club to make the art historical big time. Founded at Germany’s Düsseldorf Art Academy by Heinz Mack and Otto Piene—Günther Uecker would join in 1961—ZERO eventually expanded to become a bona-fide multinational artist network. Non-core members included the Italian Lucio Fontana, the Frenchman Yves Klein, the Venezuelan Jesús Rafael Soto, and Japan’s Yayoi Kusama. What many of them wanted was to restart art’s stopwatch at zero—the time before Year One. To do so, these artists proposed to take Western art and make it new. Again.

Organized by the Guggenheim’s Valerie Hillings, “ZERO” takes more than 180 works by Mack, Piene, Uecker, and others in order to survey the movement through paintings, drawings, sculptures, kinetic works, archival films, and light installations. Half of the works on view belong to the group’s hardcore members. The rest were authored by 37 fellow-travelers with whom Zero’s nucleus communicated chiefly through correspondence, manifestos, exhibitions, and the movement’s house organ: Zero, a magazine. As much a conventional European art movement as an arty tinkerers club with a fanzine, the Zero group—together with what scholars have recently termed the “Zero network”—presents the classic garage-band story rescued for art canonical posterity.

Like the genesis myth of, say, the Moody Blues, the Zero tale begins with the meeting of leaders Mack and Piene, but also with their effective renunciation of the era’s dominant styles—namely, Abstract Expressionism and its European variant, Art Informel. What the group abhorred about the period’s penchant for signature squiggles was its reliance on emotion and personal expression. What they wanted, instead, was a putatively scientific kind of abstraction that required infinite experimentation. Effectively, this meant adopting novel materials and processes. Traditional media like oil paint, canvas, charcoal, stone, and wood were out; nails, fire, light bulbs, aluminum, mirrors, and motorized parts were in. The group’s grail was innovation above all things. Like with earlier 20th century movements—Futurism and Vorticism, among others—the novelty was very much for its own sake.

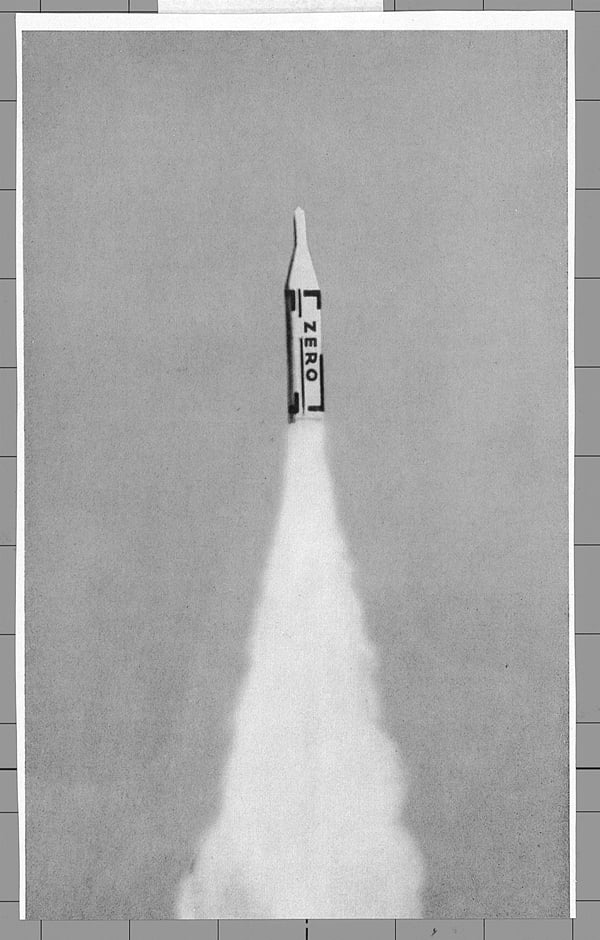

Illustration from ZERO 3 (July 1961), design by Heinz Mack.

© Heinz Mack Photo: Heinz Mack.

Despite the exhibition’s having so much of yesterday’s fresh art on view, it’s striking to note how bland and uniform much Zero work looks today. Arrayed around the Guggenheim’s spiral are multiple instances of monochrome grids that feature dots, punctures, blocks, squares, feathers, and bread rolls by (respectively) artists Bernard Aubertin, Enrico Castellani, Gianni Colombo, Jan Schoonhoven, Henk Peeters, and Piero Manzoni. When Zero creators deemed the grid insufficient, they often resorted to all-over patterns—as seen in paintings by Gerhard Von Gravenitz, Piero Dorazio, and Kusama. A third ubiquitous trait turned out to be the group’s reliance on reflective surfaces. Suffice it to say that “ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow” never looks so predictable, or dated, as when Heinz Mack appears projected on a museum wall—à la Liberace—wearing a silver lamé suit in the Sahara.

Because several gallery shows have piggybacked onto the Guggenheim’s exhibition—including Moller Fine Art’s “ZERO in Vibration/Vibration in ZERO” and Sperone Westwater’s “Heinz Mack: From Zero to Today, 1955-2014”—it’s tempting to see the Zero group’s resurgence in general, and this show in particular, as a textbook primer on overturning art world conventions. But nothing could be further from the truth. Consider, for instance, the works of Zero founders Otto Piene and Günther Uecker. While Piene made a great deal in the 1950s and ’60s of his use of single-hued paintings with circles—White Circle (1957) is a typical item—Uecker did much the same thing with multiple variations on canvas, paint, and nails. Take White Bird (1964), for example. Uecker’s most recognizable artwork, it’s nothing if not a distillation of signature style.

Both at the Guggenheim and elsewhere, there’s no dressing up the fact that the Zero group’s output has not only not aged well, today it looks downright Jurassic. Not only do yesterday’s experiments currently appear antique in these exhibitions, the effort to rope this work together—despite its infrequent surprises—itself seems a redux of age-old efforts to make top-shelf art of second-rate visual phenomena (looked at very skeptically, it resembles yet another revival staged amid an art market hungry for blue chip hits). But what about the group’s canonical value? While it’s true that Zero, and specifically the interventions of Mack, Piene, and Uecker, foreshadowed or dovetailed with existing avant-garde trends—like performance, op art, and earth art—none of the movement’s three founding artists prove fundamental to their history.

Despite excellent scholarship, the Guggenheim’s Zero show can’t help but look like what it is: a collection of period pieces. Monochrome, motorized and often shiny, Zero’s vision of the future, as laid out atop Frank Lloyd Wright’s soaring ramps, points directly at the past.

“ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s–60s” is on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through January 2, 2015.

Installation view of “Zero: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s–60s.”

Photo: Solomon R. Guggenheim/Flickr.