People

In the 1980s, Thomas Bayrle Rented a Xerox Machine by the Hour to Make Blasphemous Artworks. He’s Still Pushing Buttons Today

The celebrated German artist has two solo exhibitions on view in Berlin.

The celebrated German artist has two solo exhibitions on view in Berlin.

Kate Brown

At 8 o’clock in the morning, the artist Thomas Bayrle would rent a photocopier for one hour in downtown Frankfurt. This was in the 1980s, so these whirring contraptions were around, but were costly to buy and not easily accessible, especially if your aim was to play around.

Bayrle, his wife at the time, and a few of his students would crowd around the machine shoulder to shoulder, using their thumbs to manually distort pictures Bayrle had printed onto latex. The warped image of a Mercedes Benz, for example, would be petrified as the beam of light under the machine’s glass surface whizzed by.

“There were no shortcuts at that time, so we had to [make] it with manpower,” Bayrle told me recently in his Frankfurt studio. “But today, I wouldn’t do it like this—it’s boring.”

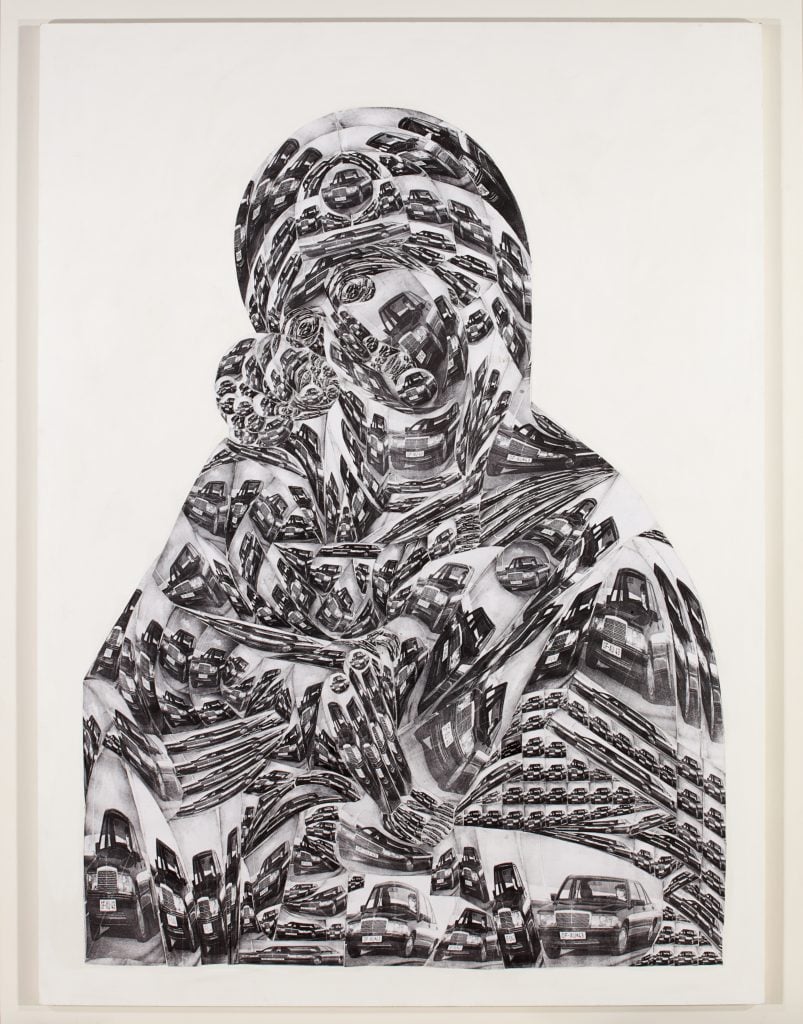

The 84-year-old recounted the story with bright eyes and bursts of energy that belied his age as we sat together in the studio, just across the street from his home. He flashed an un-cropped picture of the photocopied Benz, pinched down in eight thumbprints to create his 1989 Madonna Mercedes, now in the Städel Museum collection in Frankfurt. The final image looks like a marbled version of the icon, except that when you look closely, she’s made from a multitude of versions of the car, transformed by the artist’s self-fashioned, pre-Adobe warp tool.

Thomas Bayrle Madonna Mercedes (1989). Collector of the Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Eigentum des Städelschen Museums-Verein e.V. Photographer: © Städel Museum -ARTOTHEK

oeuvre: © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn

Ever since Bayrle began making art in the 1960s, he has been keen to transgress new technologies. He is called a Pop Art icon in Germany, and draws regular comparisons to Andy Warhol. But that’s not a complete picture of an artist who was greatly informed by the post-war political landscape, German industrialism, and the rise of China, in addition to mass media. For nearly five decades, he has explored the boundary between uniqueness and mass production, between automation and the intricacy of the artist’s hand.

Long cherished in Germany and also in Asia, Bayrle’s uptake in the U.S. came later, most recently when Massimiliano Gioni brought a major institutional survey of the artist’s works to the New Museum in 2018. Back home, Bayrle helped rear a generation of artists during his many years teaching at the prestigious Staedelschule in Frankfurt, with cohorts of students including Haegue Yang, Jana Euler, and Tomas Saraceno. Despite his clear influence, Bayrle is humble, appreciative, and interested to listen.

While his spiritual vision of industry and technology appears natural in the 21st century, it was not always this way. “It was almost blasphemy to connect meditative feelings with the mechanic world” or to “have the desire to try and link the rhythm of yourself and your body with automated machine rhythms,” he wrote in a text for a recent Gladstone Gallery show.

This interest manifested in his “superforms,” images made from other, atomized images (as in Madonna Mercedes), which have been a constant thread. Yet Bayrle, who finds sublime beauty in modern machination, has consistently innovated their execution. They exist as analog prints, delicate paintings, or as mixed-media works made from stamps, to name a few examples. Each is a petri dish made of bits of digital code. When I returned home from Frankfurt, I unfolded a newspaper he gave me to find a large portrait Kim Kardashian constructed from smartphones.

“Thomas Bayrle: Playtime“, New Museum, New York, 2018: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

In one part of a pair of exhibitions on view now at Neugerriemschneider in Berlin, Bayrle is showing anonymous robotic arms made not from solid machines, but carefully constructed out of hundreds—maybe thousands—of small warped smartphones. Bits of bright overpainting creep around the screens to make these otherwise icy blue pictures oscillate like a rippled glass window.

In the second exhibition, portraits of titans of art—Kusama, Monet, and Basquiat—have been reconstructed through cell-like stamps of a single brush stroke. The work tows a careful line jest and serious portraiture.

“I use painting when I think it is necessary,” Bayrle said as we moved around the studio. “I am not against it, and I am not for it. I use it when there is a purpose for it, but I don’t use it if it is a burden.”

Faule stellen installation view. © Thomas Bayrle, VG Bild Kunst, Bonn. Courtesy the artist and neugerriemschneider, Berlin. Photo by: Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Masses of objects and people—throngs of smartphones, groups of dancers, soldiers, cars, and planes—have always been central to his oeuvre. “The brush stroke is the most singular, original thing one can do, but I repeated it,” Bayrle said. “I used it as a cliché.”

One of the earliest examples of his superform paintings depicts his mother. Painted by hand in 1970 out of yellow rotary telephones, he seemed frustrated that it was not more perfect. (It looks perfect).

I ask why he assigned this subject that particular object. “She was always on the phone. But she was okay with the work,” he shrugged, before switching back to talking about how it was made. “I didn’t [decide to] paint this because I wanted it to be hand-done. This was just the way I could realize it, but I always wanted the work to be as slick and as anonymous as possible.”

Bayrle’s upbringing was remarkable in many ways, not least because both of his highly educated parents were steeped in the arts and German cultural institutions, which was especially rare for women at the time. The family spent the first three years of his life in Berlin while the Nazi party was in power, and when the war finally broke out, they relocated outside the city. His father was an artist, and continued to make work even when he was drafted into the German army to serve in the war. He even had a brush with Picasso in the 1920s in Paris.

“The bombing was so strong that we had to escape to a small village,” Bayrle recalled. “But this was good after a big city.” As a young boy from a metropolis, the sudden presence of nature fascinated him, and began then to draw of plants and trees.

Durchscheinen ist alles, installation view. © Thomas Bayrle, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Courtesy the artist and neugerriemschneider, Berlin. Photo by: Jens Ziehe

Yet Bayrle did not go to art school. Instead, he went to work at a textile factory before working as a graphic designer. He actually participated in Documenta 3 in 1964 as part of the publishing duo Bayrle & Jäger, and only later as a fine artist in subsequent editions.

“I was not hammering too much at being an artist,” he told me. “I was free in my visual experience. I was not afraid to work as a commercial artist one day, and the next day as a painter.”

His years at the textile factory informed how Bayrle would later interpret and make art. “It was so tough, it was better than art school. It was the pure horror of production.” His job was to fix single threads through mechanical looms to prevent them from getting caught and stalling the entire machine. The lines of threads reminded him of streets and highways, and one can see those very same highways in later works like his photo collages of cities from the 1970s and early 1980s. Some of his superforms even look a bit like woven jacquard.

“It was a pure fantasy that came from a piece of woven textile,” he said, stopping to look at me. “This is very important: people must learn to combine diverse areas and views into new views.”

Of these machines and that efficiency, he speaks both romantically and cautiously. “It was total strength, total terror.” This cocktail of awe works its way across a series of kinetic readymade sculptures made in the 2010s, including ones made from humming and hissing car engines, exposed like innards, that he showed at Documenta 13 in 2012. In another work from the next year, two disembodied windshield wipers from a Ford Galaxy, looking like bugs’ legs, flap back and forth helplessly.

Documenta 13, Kassel, 2012: Nikolaus Schletterer

Despite starting out in factory work, Bayrle did settle into an artist’s lifestyle eventually. But he was in Frankfurt, and the West German art world’s boomtowns were like Düsseldorf, where Joseph Beuys was teaching a young Jörg Immendorf, and Cologne. “Frankfurt,” he said, “was the ad world.”

Indeed, marketing and ad agencies were blossoming in the town and American companies set up outposts there; Bayrle was greatly informed by the industry, but also by the U.S. soldiers who populated the city in those post-war years. (Bayrle actually held drawing classes for soldiers for a time.)

“Frankfurt had a good kind of cheapness. It was a muddy, money town,” he said. “Artists hated it. For ‘real’ artists, Frankfurt was an impossible place. This town was America.”

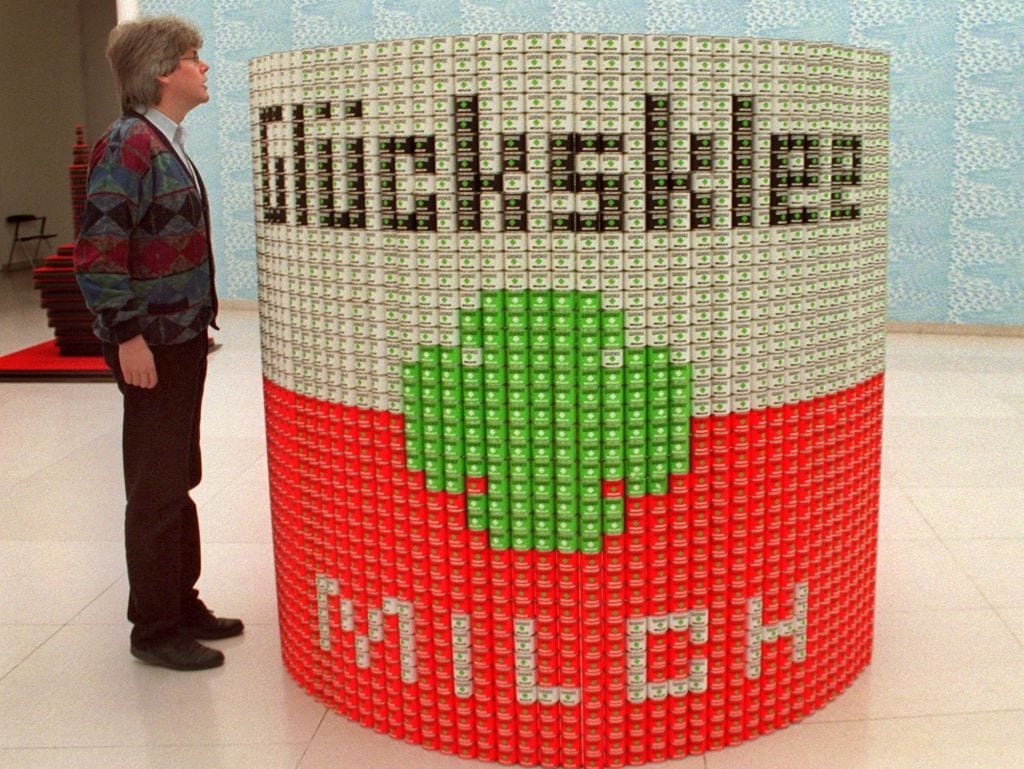

A visitor takes a look at Thomas Bayrle’s oversized Glückskleedosen sculpture at the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt am Main in 1997. Photo: Katja Lenz/picture alliance via Getty Images.

Though Bayrle floated around with Americans for a time, and while the blossoming Pop Art field was greatly inspiring him, the masses and the production lines were as much about corporate America as they were about China.

Bayrle, then a devoted communist, was active in the leftist youth and student movement in Germany which, after the war, was filled with hard-liners deeply concerned with West Germany’s failure to oust former Nazis, many of whom ended up in high-level state or corporate positions.

His work at the time—pictures of Mao, throngs of Chinese crowds eating ice cream, or a rocket superform made out of völkisch German figures and beer mugs—sought to look beyond the popular, monotone line of thinking that defined the Cold War.

“I worked in a basement with a machine. It turned out to be dangerous later, when because of the RAF, associations with communism became quite illegal,” he told me, in reference to the far-left group Red Army Faction. “Officially, it was impossible to work for these groups. They were persecuted and they were under police stress. We were friends with them before, so when they were chosen considered criminals by the police it became very dangerous for us.”

“Thomas Bayrle: All-in-One“, Institut d’art contemporain (IAC), Villeurbanne/Rhône-Alpes,

2014: Blaise Adilon

Yet Bayrle is careful to remind me that he is not simply finding poetry in industrialized society. “I am not only optimistic,” he said. “One must work with it in a positive way. But that depends on how your emotions and desires are.”

The ability to think beyond simple binaries has been an undercurrent of Bayrle’s work—and something that continues to keep his practice relevant: a recent exhibition at Gladstone brought together super-formed portraits of Kim Kardashian, Xi Jinping, and the Pope together in one gallery space. Again, this seems to be less about values and more about mass culture and our heavy consumption of images.

“With a free thing, you must do a tough thing—and with a tough thing, you work towards a free thing,” he said. “It is good to have contradictions. There always has to be a mix of planning and trying, and making errors. There should be a relaxed approach to it, and it is important that it is honest.”