People

‘We Are Always Speaking to a Mass Audience’: MoMA Curator Thomas Lax on the Advantages—and Challenges—of Art in the Digital Age

The curator also tells us about how formative early experiences shaped his understanding of the world.

The curator also tells us about how formative early experiences shaped his understanding of the world.

Terence Trouillot

In March, the Museum of Modern Art in New York promoted Thomas Lax, then an associate curator of performance and media, to full curator. Since 2014, when he came to the museum, Lax has distinguished himself through a number of exceptional exhibitions, including “Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done” (2018), “Unfinished Conversations: New Work from the Collection” (2017), and “Maria Hassabi: PLASTIC” (2016). Before that, Lax worked at the Studio Museum in Harlem under Thelma Golden.

Currently, in anticipation of the MoMA’s expansion this fall, the young curator is working on a massive rehang of the museum’s permanent collection, which promises to emphasize works by women and artists of color. Additionally, Lax is in the midst of organizing an ambitious exhibition on art dealer Linda Goode Bryant’s historic Just Above Midtown gallery, with the show set to open in 2022.

Lax’s promotion comes at a time where performance and new media have commanded the attention of the mainstream art world. Recently, artnet News spoke with Lax about the rising popularity of performance art, how his mentors have shaped his worldview, and what he’s planning for “Just Above Midtown: 1974 to the Present.”

Thomas Lax and Julie Mehretu at Skowhegan Awards Dinner. Photo by Gonzalo Marroquin/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images.

Tell us a bit about your background, and how you came to curating as a profession.

I’ve been at MoMA for the last four-and-a-half years. Previously, I was at the Studio Museum in Harlem for seven years, and that was really my formative experience in terms of doing museum and curatorial work. The Studio Museum, of course, is known as the museum that supports artists of African descent, locally and internationally. But a huge part of that museum’s [mission] is working directly with artists early in their careers, and in a continual and ongoing way.

Before the Studio Museum, I studied Africana Studies and Art Semiotics at Brown University. I was really fortunate to be able to study in the Africana Studies department. I was with a group of people who were not only committed to filling in the gaps of African American history, but who also asked radical questions around the history of black intellectual thought. [They were curious about] how that history provided not only a critique of certain Enlightenment ideals, but also offered a different worldview for understanding the place of black culture and black art-making within the broader history of civilizations and ideas. I think that experience has affected the way I try to approach all the work I’ve done at MoMA, so that it’s not simply about looking for gaps and filling them, but also about asking broader questions about what those gaps reveal about the value systems at play.

Did you grow up surrounded by art? Was it a constant part of your life when you were young?

I would say so, yes. I grew up in New York City, and both of my parents, and the rest of my extended family, really felt all aspects of culture were important. It was part and parcel of our lives. Art and culture were not add-ons or a luxuries, but were really an essential part of what it meant to be in the world. I think a lot of my understanding culture as a sustaining force of subsistence comes from the fact that my family really understood it as an important part of life.

Earlier in my life, I was a performer. I sang and danced. I was part of an education that emphasized those things. So I took up the practical aspects of learning how to sing and read music. I was in the children’s chorus at the Metropolitan Opera, which gave me a sense of discipline. In third grade, having a job where you left school for the day to perform with adults gave me a sense that art was really work, and the hard work it took to really master a craft was something people dedicated their lives to.

Photo courtesy of Thomas J. Lax Instagram.

Let me ask you about Okwui Enwezor. You posted a photo of him with Glenn Ligon on Instagram soon after his death. In the comment, you mentioned that you “shadowed” Okwui for a week. What was that experience like? And more broadly, how did Okwui Enwezor influence you and your career?

I was a fellow at the Center of Curatorial Leadership, and as part of that program, you’re matched with a museum director. And I was matched with Okwui Enwezor and got to shadow him for a week in Munich when he was the director of Haus der Kunst.

He was somebody that many people of my generation—but also a generation older than me—recognized as having a vision of the world that he wanted to make real. There was this idea that it was possible to describe a relationship between people working very far way from one another, and I think seeing him up close offered me an opportunity to bear witness to his encyclopedic brain.

In that photo with Glenn… he and Glenn had a twenty-year-plus relationship, and I think that affirmed the things that I learned through other mentorships. In other words, this academic approach to scholarship and institution-making was made good through real relationships with living artists. I think Okwui embodied those two things: a real care for living artists, and a deep and rigorous attention to historical scholarship.

But I’m super lucky in that I have been the beneficiary of mentorships from a number of people. From my undergrad [career] forward, I got to work with Saidiya Hartman, who was and continues to be a mentor of mine; Kellie Jones at Columbia for graduate school; I worked for Thelma Golden at the Studio Museum, and in that time was working directly with Naomi Beckwith and Christine Y. Kim. And then coming to MoMA, I’ve gotten to work with many of the senior curators here, including Kathy Halbreich, who was the associate director. And what all those people have in common is a real commitment to black feminist practice.

Do you see that as a bigger trend within curatorial practice today?

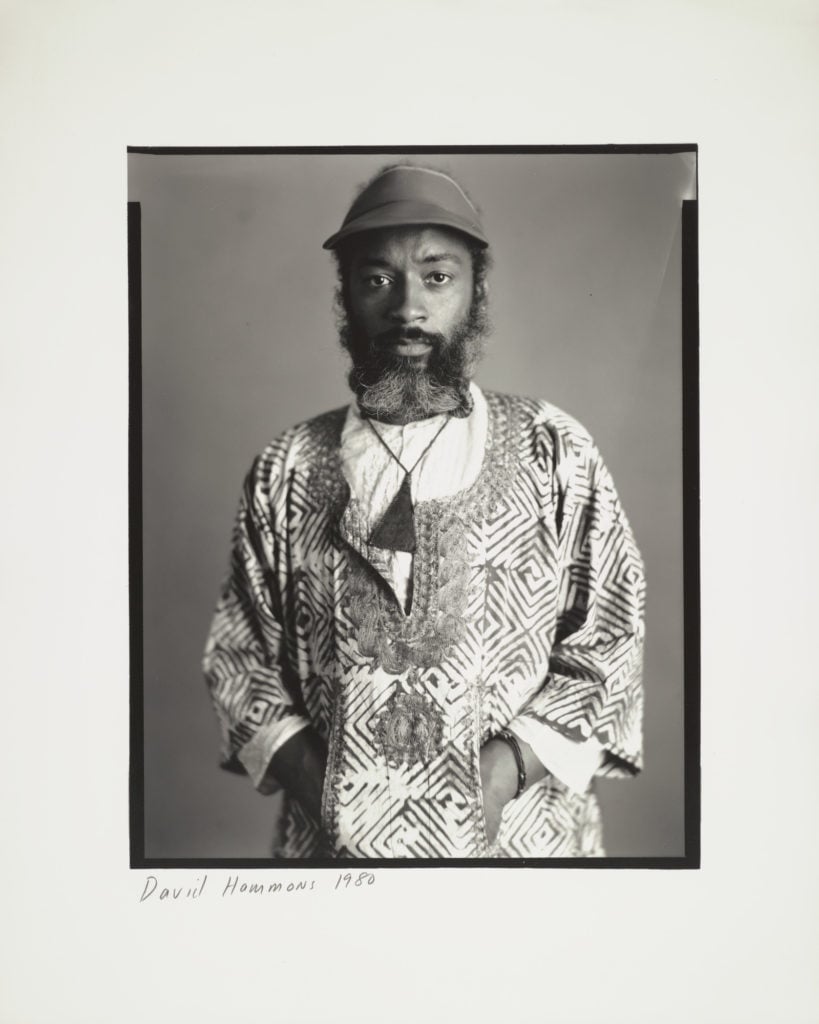

I think we’re in a moment where you would be hard pressed to find any museum director in this country who doesn’t hope, in the next five to ten years, to show more women color and more artists of color. There are a number of us [curators] who are in the field, and I think we’ve come up collectively, and can now rely on one another to understand the change we want to see. As David Hammons said, I’m not coming up in this white cube by myself.

Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, Photograph of David Hammons (1980). © Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, courtesy the Museum of Modern Art Archives.

Let’s talk about performance. MoMA has been doing good job presenting performance in exhibitions—there was Marina Abramović, Judson Dance, etc.—but other museums have been more aggressive in acquiring performance art. What’s your perspective on the strategy for collecting this kind of work? Is that something that interests you?

The way that I’ve approached this question has benefited from a lot people’s work before mine. At MoMA in particular, the first two chief curators of the department that I work in, which is the newest curatorial department at the museum, really set the groundwork—Klaus Biesenbach and Sabine Breitwieser—and then, of course, Stuart Comer, who is the current head of the department, and also Ana Janevski, who’s been in the department for eight years now. I think we’ve exhibited wonderful examples like the ones you’ve mentioned and others.

I think what that work has shown is that collecting performance is an idiosyncratic and kind of case-by-case practice. How you try to make a road map for the future has to respond to the way artists envision the afterlife of their projects. You have to use the model of their approach and build a structure around that.

There seems to be an obvious shift, where museums have been placing a stronger emphasis on showing performance and the moving image. MoMA, more specifically, is dedicating an entire new space to the medium. How do you explain this phenomenon and what are your feelings about its rapid growth in the mainstream?

Right now, the nature of how we communicate means that we are always in some ways speaking to a mass audience. You’re no longer working on one level, but with an amorphous group of people who are algorithmically oriented to like or dislike something. That is why, on the one hand, performance and media are relevant today.

On the other hand, there’s a version of that that becomes one big museum of ice cream, in which we’re spending our lives following things that alienate us from ourselves, and makes us feel totally depressed. I think MoMA—as much as it has to be responsive to many millions of people who are walking through the doors—is also a place that believes in research and scholarship and critique, whatever that means today.

That allows us to show a exhhition like Maria Hassabi’s “PLASTIC,” where you are confronted with a body lying there in front of you. So you are forced to deal with seeing this person as they are circulated online, but also to actually deal with them in real time and space. I think that performance offers a chance to shuttle between these different registers of how culture appears.

Maria Hassabi, “PLASTIC” (2015) live installation photograph. © Maria Hassabi, 2019.

Finally, tell us a little about the show you’re organizing, “Just Above Midtown: 1974 to the Present,” which chronicles the gallery founded by Linda Goode Bryant.

[Part of the show is about] what happened at JAM. Some people within in the art world—the black art world—know it as an alternative art space, a storied and iconic institution that Bryant started in 1974 and ran on 57th Street in the middle of the major commercial art gallery district. But JAM moved downtown a few years later and turned into a nonprofit, and also into a laboratory for artists to make work in front of an audience in a more responsive way.

So for example, David Hammons, at the very first JAM exhibition, showed a work that looked like Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912), but he made it out of greasy, brown paper bags, which caused a stir among other artists. People were saying, “Why are you using these cheap, dirty materials when we have very few places for black artists to show our work. Why are you emphasizing this abject side the culture?” Linda stood steadfast by David, but also created an open dialogue for artists to ask questions about what constituted black art, and in what ways black art had to represent black people.