Today, Polish-American artist Morris Hirshfield is considered one of the most significant self-taught artists of the 20th century. But this was not always the case. The term “Outsider Art” was coined in 1972, well after Hirshfield’s death in 1946, but his paintings still suffered from the critical prejudice that frequently accompanies art that is made outside of mainstream modes and contexts. In the decades since, Hirshfield’s contribution as an important Modernist painter has been frequently overlooked, and his work has been relegated to the footnotes of art history.

The American Folk Art Museum (AFAM) in New York has attempted to rectify that, by mounting the most comprehensive exhibition to date of the artist’s work with “Morris Hirshfield Rediscovered.” The critically applauded show, on view through January 29, 2023, seeks to not only introduce Hirshfield to a contemporary audience, but also solidify his standing within the greater trajectory of Modern art and rectify years of critical neglect. And unlike the shows Hirshfield was involved in during his lifetime, this AFAM exhibition has been met with widespread acclaim by critics and audiences alike.

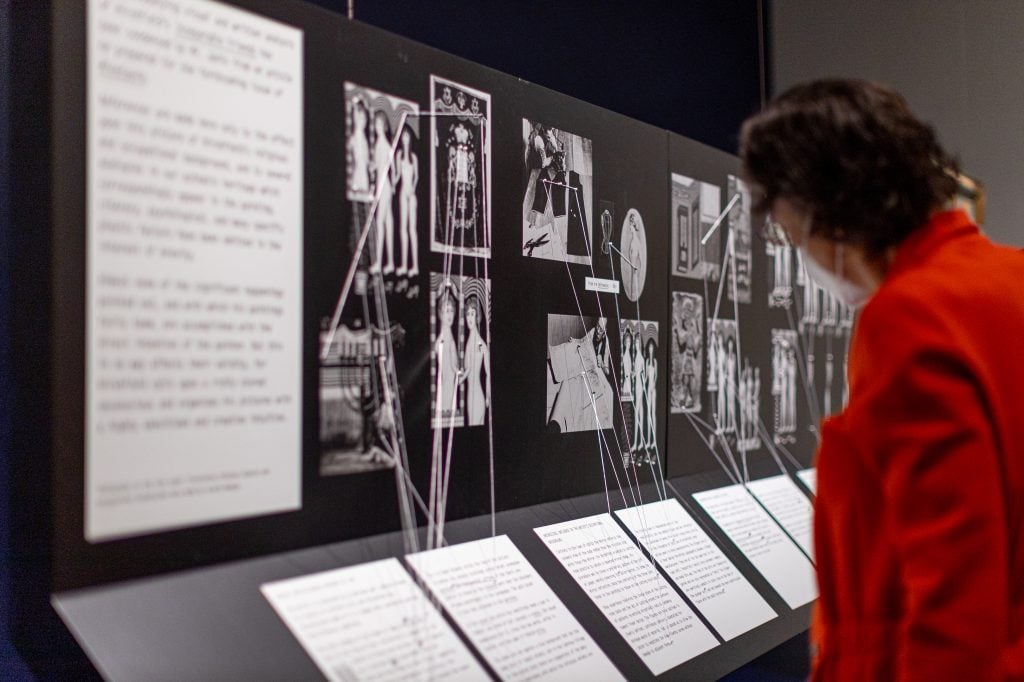

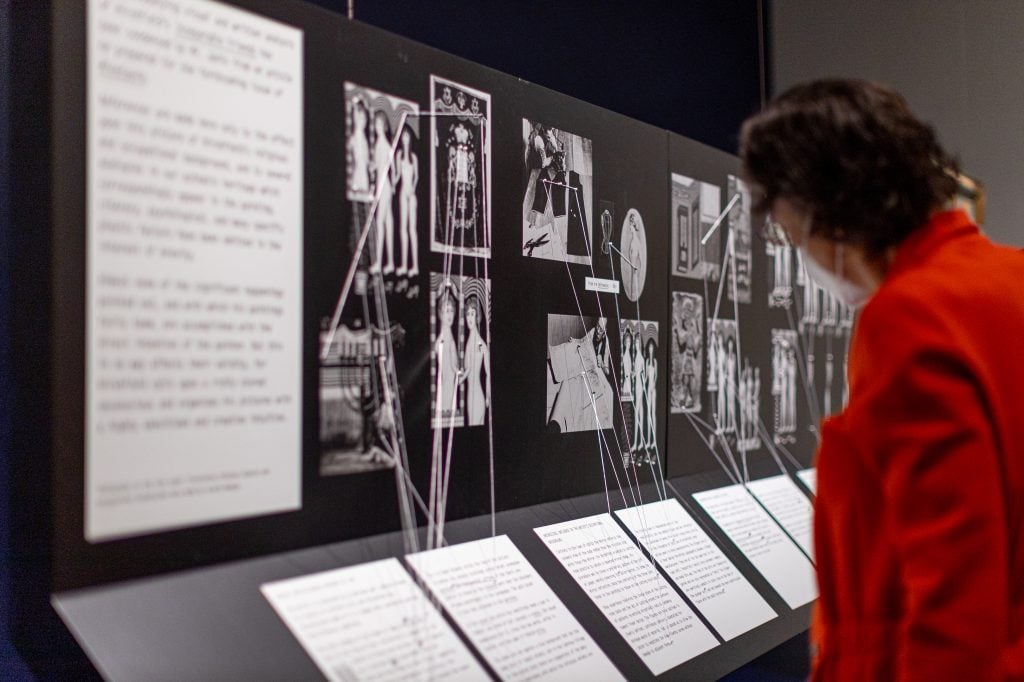

Installation view, “Morris Hirshfield Rediscovered.” Courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York.

Born in 1872 in Poland, Hirshfield led a life largely set apart from the art world—although he dabbled in wood carving and created a sculpture for his local synagogue as a teenager. He immigrated to New York City at age 18, where he initially worked in a women’s apparel factory, first as a pattern cutter before working his way up to tailor. Eventually, he left the factory and went into business with his brother, Abraham, opening a small women’s coat and suit shop.

After 12 years, the shop was shuttered and Hirshfield opened “E-Z Walk Manufacturing Company” with his wife, Henriette. The most successful items produced were “boudoir slippers”—ornate, comfortable shoes meant for home wear—which greatly contributed to the company’s growth. At its height, the business had more than 300 employees and it grossed roughly $1 million dollars a year. The house slippers were arguably Hirshfield’s greatest business success, and 14 of his patented designs from the 1920s were meticulously recreated by artist Liz Blahd for the AFAM exhibition as an homage to this facet of the artist’s life.

Celebrating this novel and intriguing exhibition, we did a deep dive into the life and work of Hirshfield and found three incredible facts about the artist to give viewers more insight into his work.

Installation view, “Morris Hirshfield Rediscovered.” Photo: Eva Cruz/EveryStory. Courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York.

All of Hirshfield’s paintings were made in the last seven years of his life

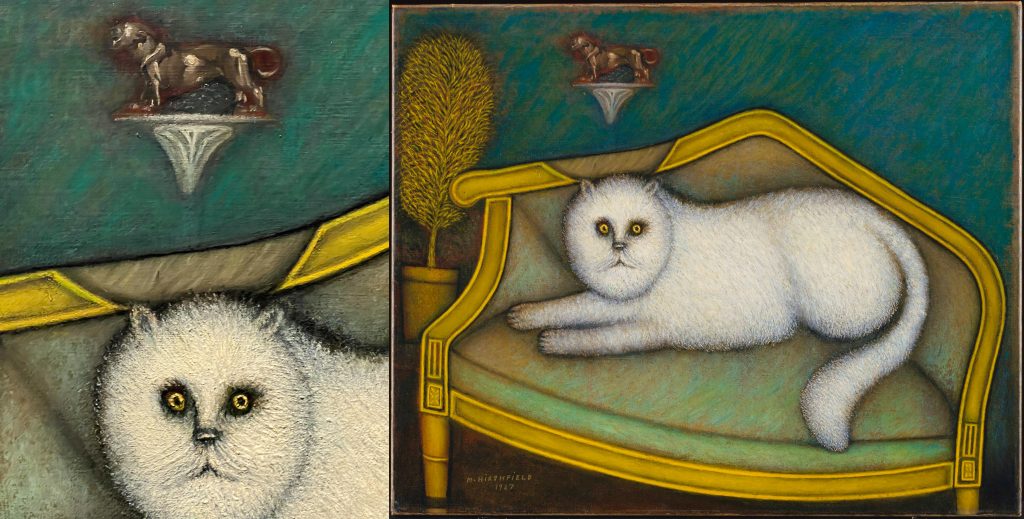

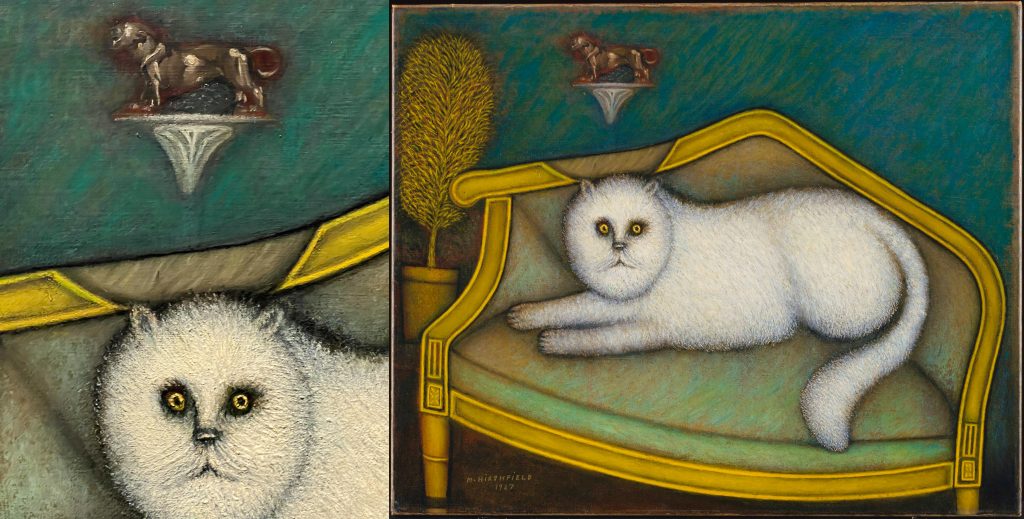

Morris Hirshfield, left: Angora Cat (detail) (1937–39), right: Angora Cat (1937–39). Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection. © 2022 Robert and Gail Rentzer for Estate of Morris Hirshfield / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

With an incredibly diverse and varied body of work, it would seem to follow that Hirshfield had a long and storied artistic career, or at the very least a history of informally experimenting with painting. But he spent the majority of his professional career working in women’s apparel and footwear. Forced to retire in 1935 due to failing health, Hirshfield only began to paint at the ripe age of 65. The seemingly immediate ingenuity and resourcefulness with which he approached his practice can be seen in some of his first paintings, like Angora Cat (1937–39). The support for this work was a preexisting painting that hung in Morris and Henriette’s Brooklyn apartment; the lion figurine set on a decorative shelf above the cat’s head is a remnant of the overlaid painting, cleverly incorporated into the new composition. The extreme detail that Hirshfield paid to every facet of his paintings, such as including repeating, intricately detailed patterns across backgrounds and costumes, indicates a rigorous pace to his artistic output. Together, Hirshfield’s oeuvre of nearly 80 paintings were entirely created in the last seven years of his life—perhaps a cogent reminder that it’s never too late to start something new.

Hirshfield’s first major retrospective led to the

museum director’s demotion

Installation view, “Morris Hirshfield Rediscovered.” A recreation of part of the Museum of Modern Art, “The Paintings of Morris Hirshfield” (1943). Photo: Eva Cruz/EveryStory. Courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York.

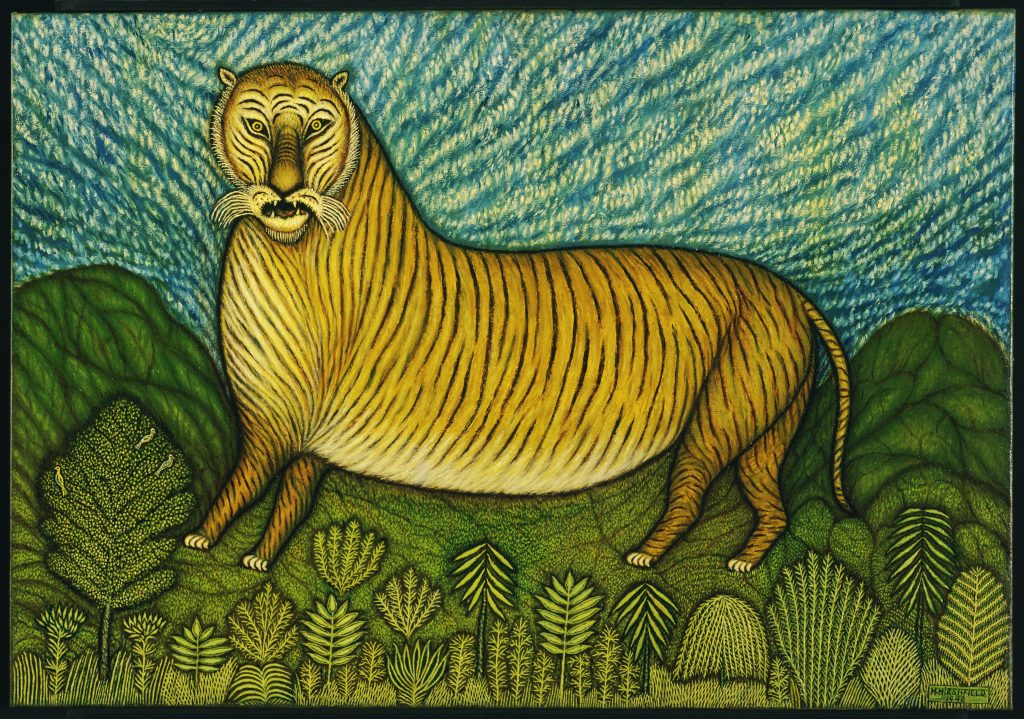

One of the most significant (perhaps even infamous) events of Hirshfield’s relatively short career as an artist was his 1943 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York—which made him the first self-taught artist to garner such a comprehensive show at the museum. According to the press release, “The Paintings of Morris Hirshfield” featured 30 “primitive paintings” and was installed under the direction of Sidney Janis, a supporter of Hirshfield’s work and an influential New York dealer and collector who was at the time a member of the museum’s advisory committee. The show was a critical failure, and the press it received was overwhelming negative—with art critics collectively referring to Hirshfield as the “Master of Two Left Feet,” alluding to the planar perspective the artist used in his compositions, particularly of women. Though of course there were other contributing factors, the influx of bad press caused by the exhibition led the trustees of the museum to demote director Alfred Barr—who deemed Hirshfield’s Tiger (1940) an “unforgettable” modern animal painting—before the show had even closed. The exhibition at the AFAM, however, has reclaimed the moniker for Hirshfield, with the catalogue accompanying the current exhibition titled Master of Two Left Feet: Morris Hirshfield Rediscovered, written by art historian Richard Meyer.

The Surrealists loved his work

Morris Hirshfield, Girl with Pigeons (1942). Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection. © 2022 Robert and Gail Rentzer for Estate of Morris Hirshfield / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Despite mainstream criticism of Hirshfield’s paintings, many Surrealists working in New York at the time embraced his singular style. Marcel Duchamp and André Breton were both fans of Hirshfield’s intriguing and unique paintings, and Breton included Girl with Pigeons (1942) in the seminal “First Papers of Surrealism” exhibition of 1942—the first major Surrealist art show in the U.S. That same year, examples of Hirshfield’s work were documented in the home of Peggy Guggenheim, in a photoshoot taken by Hermann Landshoff. In these images, Surrealist juggernauts Duchamp, Breton, Leonora Carrington, and Max Ernst (Guggenheim’s husband at the time), are shown collected around and apparently transfixed by Hirshfield’s Nude at the Window (Hot Night in July) (1941). In 1945, Hirshfield was asked to contribute an artwork for the cover of the October issue of View: The Modern Magazine, a periodical that advocated for avant-garde art, with an emphasis on Surrealism. Hirshfield created a new piece featuring one of his signature flattened women on a meticulously detailed blue field, surrounded by three birds and adorned in geometric flowers and a sash.