Art History

Alex Katz Painted Hundreds of Portraits of His Wife—Here Are 3 Things You Should Know About His Most Famous, ‘Blue Umbrella II’

The iconic painting is currently on view in "Alex Katz: Gathering," at the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

The iconic painting is currently on view in "Alex Katz: Gathering," at the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Annikka Olsen

American figurative painter Alex Katz has developed an artistic style that is immediately recognizable. Whether seeing his work from across an art fair, through a gallery window, or on the page of a book, you can tell: that’s a Katz. His flat planes of color and crisp outlines recall mid-century advertisements, and the refusal of traditional point perspective creates a singular optical experience.

Born in 1927 to Russian émigré parents and raised in Queens, Katz first studied art at Woodrow Wilson High School before enrolling at the Cooper Union Art School in Manhattan in 1946. There, he received traditional Modern art training, which emphasized the tradition of painting from drawing. In 1949, and again the following year, Katz attended the summer session at the Skowhegan School for Painting and Sculpture in Maine, where students were encouraged to paint en plein air. This proved pivotal for Katz, and he has cited painting in this manner, directly from life, as the initial reason he devoted himself to painting, and it continues to be a vital part of his practice today.

Over the next several years, Katz worked to develop what has come to be known as his signature style—and he has said he destroyed upwards of 1,000 paintings in the 1950s during this pursuit. Over the course of the following decades, Katz expanded his practice to include a wide variety of printmaking techniques, and the genres of portraiture and landscape gained prominence in his work.

Blue Umbrella II (1972) is one of—if not the—most famous of Katz’s paintings. The piece centers on the face of a woman with introspective almond eyes that seem to not even register the rain, which is rendered as incessant streaks across the canvas and as glossy teardrops dripping from the corners of the umbrella. The coral paisley of her headscarf and the umbrella’s two shades of bright blue emphasize the otherwise muted palette of the canvas. The composition is analogous to a film still from a mid-century classic, and brims with drama. It is exemplary of the artistic style that has made Katz’s oeuvre so iconic.

Installation view, Alex Katz: Gathering, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Photo: Ariel Ione Williams and Midge Wattles. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

And even at the age of 95, Katz doesn’t seem to be slowing down. Last month, a major career retrospective of the artist’s work, “Alex Katz: Gathering,” opened at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and runs through February 20, 2023. Surveying eight decades of artistic production—from early pen on paper drawings from the 1940s to work made as recently as this year—the focused, purposeful evolution of his work is apparent.

Marking this exhibition and Katz’s incredible career, we’ve taken a closer look at Blue Umbrella II and found three intriguing facts to help viewers gain a little more insight into Katz’s work.

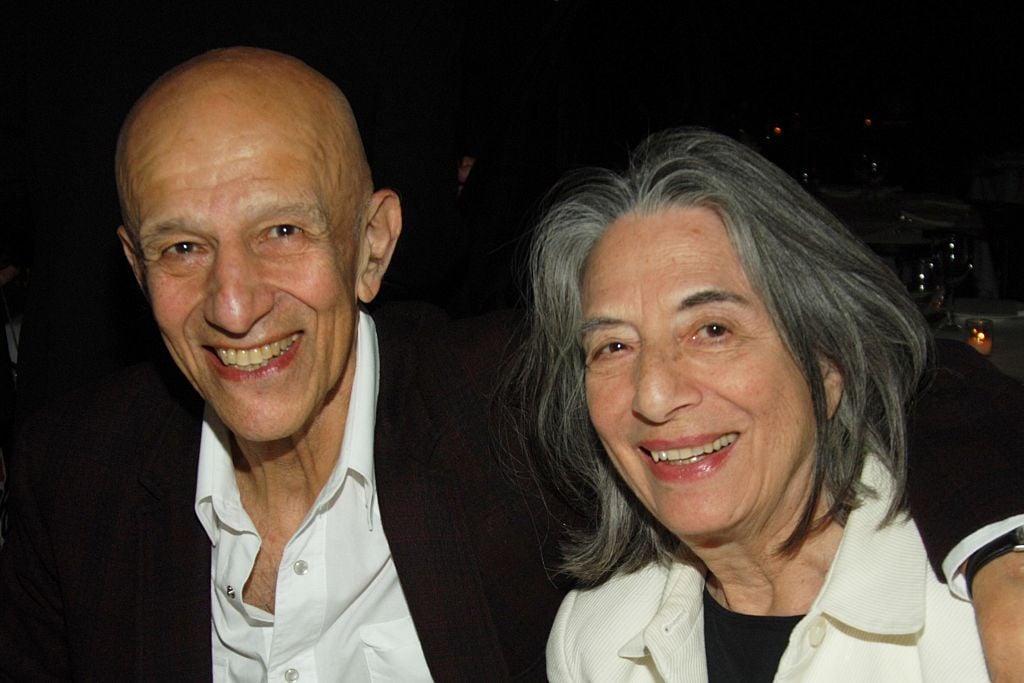

Alex Katz and Ada Katz, 2006, in New York City. Photo by Joe Schildhorn/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images.

Alex Katz met Ada Del Moro at a gallery opening in the East Village in 1957. Del Moro was a research biologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and one of their first dates was to a Billie Holiday concert. The very first portrait Katz made of Ada was the same year they met, an oil on Masonite work of her seated with hands demurely crossed. This work marked the beginning of Katz’s serious interest in portraiture, as well as the start of a lifetime’s worth of portraits of Ada.

The pair were married the following year, in 1958, and Ada became one of the most repeated subjects of Katz’s work. In total, Katz has created more than 250 portraits of Ada Katz, including Blue Umbrella II, which was made almost exactly 15 years after the first Masonite portrait. It highlights the evolving and aging relationship between husband and wife, artist and muse. With portraits of Ada spanning over six decades, Katz has portrayed Ada as everything from a demure 20-something to a mother with child to a mature woman—individually they represent Katz’s dedication to the genre, but together they illustrate the artist’s never-wavering dedication to the love of his life.

View of Alex Katz’s studio, 2016, in New York. Photo by Catherine Panchout/Sygma via Getty Images.

Katz has developed an approach to painting wherein he paints “faster than [he] can think,” tapping into a meditative stream of consciousness that eliminates the possibility of over contrivance or second guessing. Katz also frequently uses the “wet-on-wet” style of painting—where different colors and layers are applied while the paints remain wet—including in Blue Umbrella II, which gives it and others like it their even and luminous swathes of color. The wet-on-wet method has been employed by artists ranging from 17th-century Dutch master Frans Hals to 1980s how-to painter Bob Ross, and it allows for a level of immediacy and decisiveness that is too easily circumvented by using slower modes of painting.

Despite working at such a rapid pace, you won’t find paint splatters or spills in Katz’s studio or workshop. Though the idea of an artist’s studio conjures images of built up, dried paint on floors, walls, and brushes, the clean Minimalism of his work extends into workspace, and visitors have noted its pervasive tidiness and cleanliness.

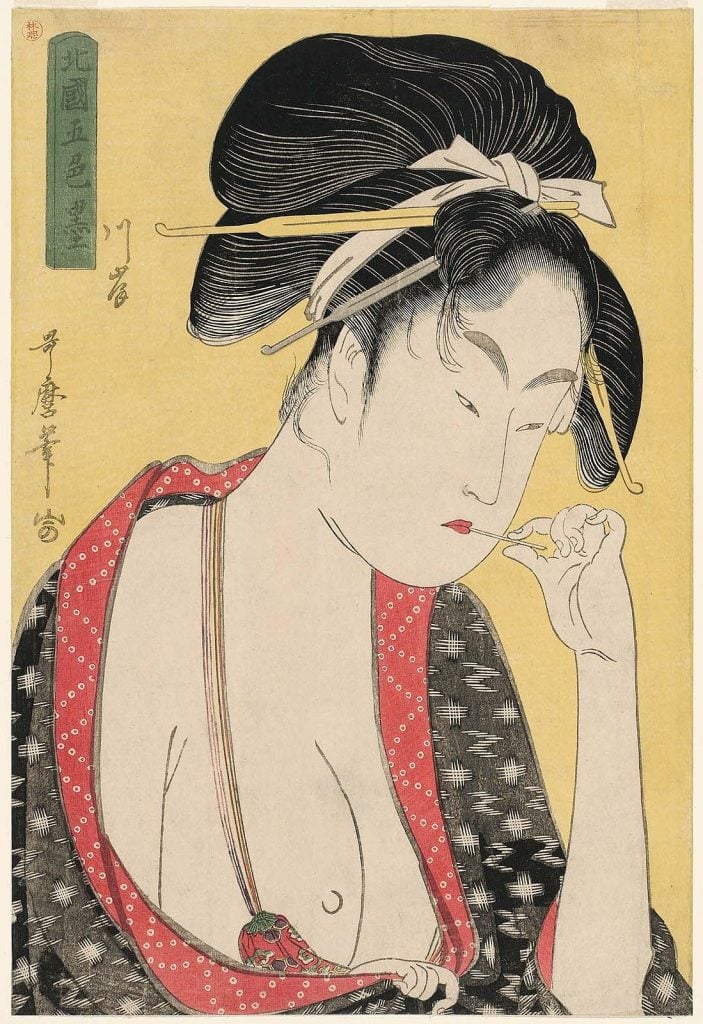

Kitagawa Utamaro, Moatside Prostitute (Kashi), from the series “Five Shades of Ink in the Licensed Quarter” (Hokkoku goshiki-zumi), (ca. 1794–95). Collection of the Museum of Fine Art, Boston.

Perhaps the most obvious influences on the development of Katz’s style were his figurative painter contemporaries, which he was also close friends with, such as Jane Freilicher, Fairfield Porter, and Larry Rivers. Katz has also cited Modern masters like Edward Hopper, Henri Matisse, and Henri Rousseau as key sources of inspiration. However, Katz also looked to older art history as well as outside the visual arts for inspiration. Poets such as John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, and Edwin Denby moved through the same circles as Katz, and the reciprocity of their esteem for one another’s work undoubtedly helped shape his creative output.

Intriguingly, Katz has also referenced historic artists figures like 18th-century Japanese artist Kitagawa Utamaro as a source of inspiration. Utamaro’s pared-down line work yet emotive compositions have a minimalist essence that can be compared to what is found in Katz’s work. Additionally, when Katz’s career was first gaining momentum in the 1960s, the highly polished world of the Abstract Expressionists and flashy Pop artists was reaching its peak. Artists like Utamaro portrayed a “bohemian world” that Katz has always identified with, one that is inherently antithetical to the higher echelons of what is considered fine art.

Katz has also noted that exposure to the work of El Greco while still in art school was an early influence as well. Though the visual similarities between the two artists’ work are scarce, their specificity of perspective is a common element. Katz recognized that El Greco’s paintings were made to be viewed from a certain vantage, and within a certain environment—namely one lit by candlelight. In a similar manner, Katz creates his work with their own internal perspectival logic. This can be seen in works like Blue Umbrella II, where depth is alluded to through elements like the spokes of the umbrella, but the composition still reads as flat due to the minimal use of highlights and shading throughout.