Tippet Rise, the brand new art park and performing arts center in Fishtail, Montana, sits midway between Billings and the least used of the four entrances to Yellowstone National Park.

Think of it as Storm King meets Caramoor or Ravinia, the Inhotim of the mountains, or the Naoshima of the West. Cowboy hats are optional, but a smattering of visitors earlier this month were wearing them, without a trace of irony.

Luckily for those who attend the chamber music programs, the concert of bleating and mooing of its 3,000 sheep and 500 cattle is conducted largely on the outskirts of the combined six ranches that were bought almost simultaneously by Tippet Rise founders Cathy and Peter Halstead.

The site was named for Cathy Halstead’s mother, who went by the nickname Tippet. Cathy’s father was Sidney Frank, the self-made booze baron who created Grey Goose vodka (sold to Bacardi for $2.3 billion) and who was—according to legend—rarely seen without a custom-made Davidoff cigar in his mouth.

Cathy and Peter Halstead are longtime philanthropists who are less known in the art world than in the halls of higher education and classical music. The duo strives, they have said, “to make Tippet Rise a place where people feel the profound connection between their own inner nature and the natural world around them, a place where great music collaborates with the big sky and art is rooted deeply in the land.”

Ensamble Studio (Antón García-Abril and Débora Mesa), Domo. Photo by Andre Costantini. Courtesy of Tippet Rise.

“They’ve brought an intensity of culture into spectacular mountains and this sense of the Wild West, which is huge,” said Mark di Suvero, the abstract expressionist sculptor and National Medal of Arts winner. At 82, he just installed three artworks on the 12,000 acre ranch.

“The inventiveness, of what Peter and Cathy have done is just incredible,” he says, adding, “they have shared it with the intensity of real aesthetic perception.”

Two Di Suvero sculptures and one painting are among nearly a dozen artworks at Tippet Rise that are a combination of new, site-specific commissions and loans. Music has been going strong all summer long—sometimes at, around, or beneath Tippet Rise’s outdoor sculptures, and more often in the 150-seat music barn or the outdoor band shell next door.

While many of the visitors this past weekend were enthusiastic local families—including a trio of Trump supporters in trucker hats—there is already some resistance from neighbors. Among a litany of relatively petty complaints (construction dust and the perennially bad driving habits of workers), one in particular stands out: One local warned a reporter from the Stillwater County News that if the mostly classical music program planned for Tippet Rise hit her ears, she would put on her own “counter concert,” which involves singing over a loudspeaker to Joni Mitchell’s 1970 hit “Big Yellow Taxi.”

Di Suvero, clad in paint-speckled jeans and eating a warm brownie from Tippet Rise’s on-site catering, was in Fishtail last week for a special concert to celebrate the purchase of his works. He and the Halsteads sat for interviews at one of the campus’s airy, loft-life residences built for visiting visual and performing artists.

The Olivier Music Barn at Tippet Rise Art Center. Photo by Andre Costantini. Courtesy of Tippet Rise Art Center.

Until this past year, Di Suvero’s Beethoven’s Quartet (2003) had a home at Storm King in upstate New York. Originally, the Halsteads said they tried to buy a newer work from Paula Cooper Gallery, but were too late. After they wooed the artist with a studio visit and a dinner with “some old Barolos,” according to Peter, Di Suvero helped them negotiate the purchase of the artwork and its 2,100-mile move to a low meadow among the hills of Fishtail.

The 24-by-30-foot steel sculpture comes with rubber mallets. “You can play it. And it isn’t often that you are allowed to hit with hammers a giant piece of stainless steel!” Di Suvero emphasized with glee. “It acts like a giant gong! And people love that!”

But the artist’s emotions shift quickly. His blue eyes filled with tears as he recalled a performance in Manhattan of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony shortly after his return from a four-year-long self-imposed exile in protest of the Vietnam war in 1971. “There are moments of music that can change your life,” Di Suvero said. “And Beethoven did that for me.”

Later, during an on-stage conversation with Christopher O’Riley, an esteemed pianist and host of NPR’s “From the Top” who serves as musical director for Tippet Rise, Di Suvero said, “There is a dream that all sculptors have shared which is to take a piece of music and turn it into sculpture, which is not easy to do.” (The Saturday concert in his honor included, naturally, Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 15 in a minor, Op. 132, with some Schubert and a few encores thrown in.)

Di Suvero’s Proverb (2002) is also musical, though less obviously so. It is often compared to a metronome because of the pendulum that swings freely from its twin A-frame supports. It stands 60 feet tall yet is dwarfed by the hillsides of the valley in which it now resides. Until the Halsteads bought Proverb, it stood for more than a dozen years beside I.M. Pei’s Meyerson Symphony Center in Dallas.

Ensamble Studio (Antón García-Abril and Débora Mesa), Beartooth Portal (2015). Image courtesy of Tippet Rise/Iwan Baan. Photo by Iwan Baan.

All but two of Tippet Rise’s sculptures sit atop impressive mesas or are nestled in the hilly folds of the land, creating surprising moments as you drive or walk the isolated looping gravel trails. (“Discovery” is a key theme for the Halsteads.) From each artwork, you can see at most one other work in your field of vision. And that’s a deliberate choice, said Alban Bassuet, Tippet Rise’s director, to encourage “conversations” between specific sculpture pairings.

Tippet Rise would still be worth the trip if it housed nothing but the three site-specific commissions by Spanish born Antón García-Abril and Débora Mesa of Ensamble Studio, who also have a project entitled Supraxtructures Vs. Structures Of Landscape (co-produced by Tippet Rise) on view in the Arsenale the architecture biennale in Venice. (He is an architecture professor at MIT and a founder and director of the MIT’s Prototypes of Prefabrication Research Laboratory or POPLab.

Domo, is a 98-foot long, 16-foot high, three-footed bowl that was designed specifically for its acoustic properties as a shelter for outdoor concerts. It sits on a flat plain, its upper level filled with a dirt cover that Bassuet said he expects will soon sprout plants.

The couple created Domo and its siblings Beartooth Portal and Inverted Portal in situ by digging holes and using the Montana earth to cast them. Each portal piece comprises two roundish concrete shells that were flipped up to create a gate and each is approximately 25 feet tall.

All three of Ensamble Studio’s works make their home on wide, flat pieces of land –all the better to admire their shape from a distance and their scale as you approach.

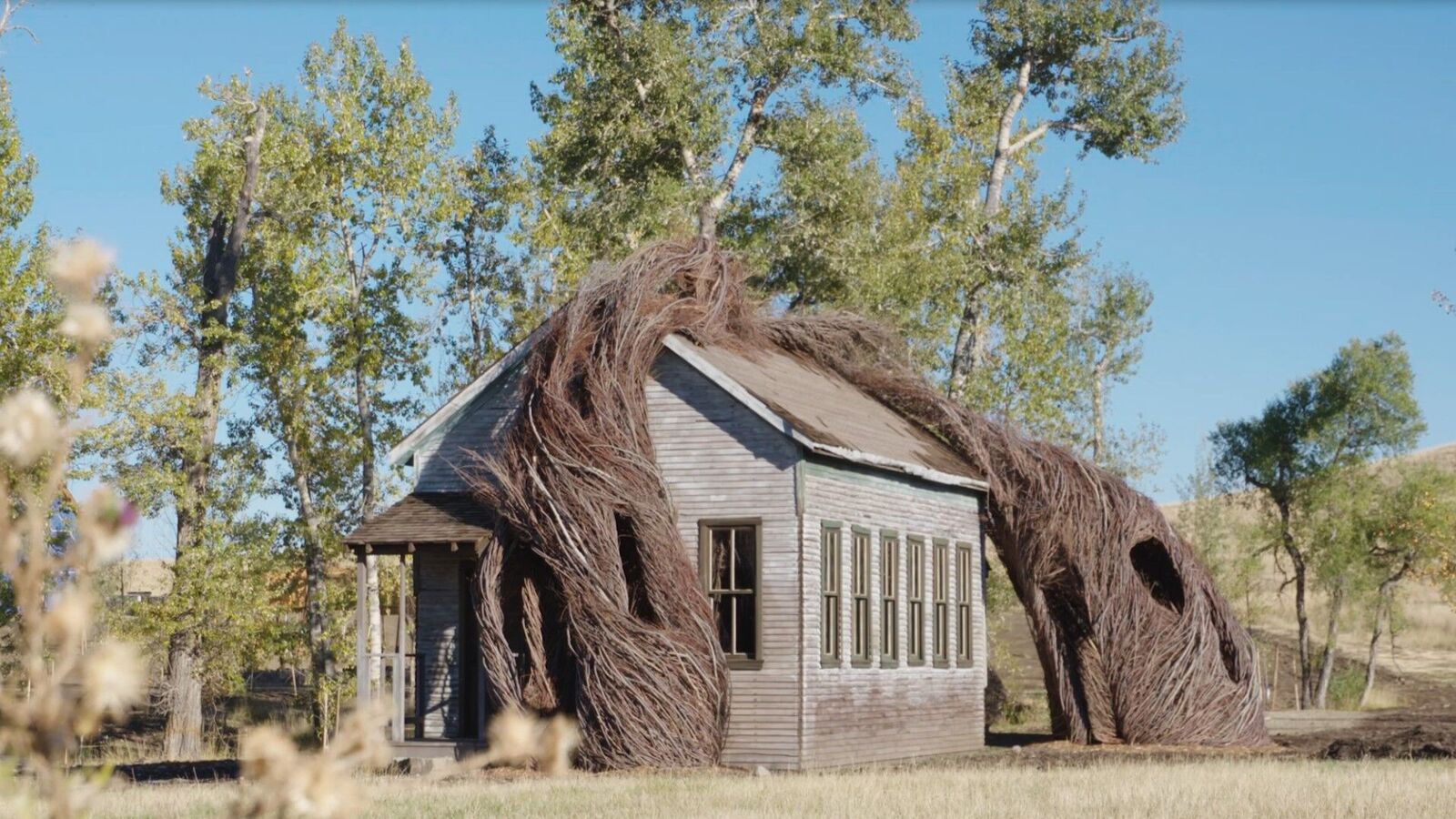

Patrick Dougherty, Daydreams (2015). (School house in collaboration with JXM & Associates LLC and CTA architects.) Image courtesy of Tippet Rise/Djuna Zupancic. Photo by Djuna Zupa.

Stephen Talasnik‘s Satellite No. 5: Pioneer (2015), is but one of a series of nomadic wooden structures, collectively titled Satellite, that will be made and sited throughout the campus. Nearly 35 feet tall and 40 feet long, the sculpture is made of wood planks and logs, some shod in rusted steel, and looks a little like the jungle gyms with the swaying plank bridges kids love so much; one can’t help but want to climb it. The yellow cedar, which will gradually gray with weather exposure, currently stands in lovely contrast to the green vale in which this piece rests. On Saturday, the sculpture became a stage for a rare performance of John Luther Adams’s Inuksuit, played by 45 percussionists including members of the nearby Billings Symphony and the Excelsis Percussion Quartet.

Patrick Dougherty’s piece Daydreams (2015) is a newly commissioned replica of a frontier-era schoolhouse that has been crafted to look like a historical ruin overtaken by thick rivers of twisted willow vines. If one were to happen upon it as one sometimes encounters abandoned 19th century miner’s cabins in the west, it would make quite an impression and be more impactful as a comment on human interaction with nature. But situated as this one is directly adjacent to the main facilities of the campus and in view of the business end of the outdoor band shell and the music barn, it lacks the power of its sister sculptures at Tippet Rise.

Alexander Calder’s Two Discs (1965) is the first artwork you see when driving towards the center of the Tippet Rise campus. It is so black it is almost a shadow of itself against the big Montana sky, even as dark comes and the stars turn the green land grey and the blue horizon a deep purple. It is on loan from its longtime home at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington DC as part of a lending program being touted by its director, Melissa Chiu, who trekked to Tippet Rise earlier this summer.

“It’s not every day that a project of this scale comes about!” Chiu said in an email after her trip. “The combination of creative arts, music and sculpture, in the natural environment makes it very special.” She also alluded to the possibility of “many more curatorial and programming collaborations with Tippet Rise in the months and years to come.”

But not everything onsite takes your breath away. Like Dougherty’s work, Calder’s mobile Stainless Stealer (1966), which is also a Hirshhorn loan, seems ill-placed, hanging as it does off an eave in the back of the music barn. It gets no opportunity to be seen against the landscape, or even with much natural light. A seatmate at one concert didn’t even notice the 15-foot mobile dangling above him. Among the massive amount of land available, surely a better spot can be found for this seminal work.