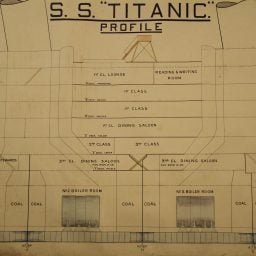

On this day 111 years ago, the legendary RMS Titanic struck an iceberg, just four days into the ship’s maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City. Over 1,500 people lost their lives, with casualties highest among crew members and third-class passengers. Even over a century later, the Titanic remains the most famous—and infamous—shipwreck of all time.

Although nothing can compare to the loss of life, a footnote to the event is the loss of cargo. Along with commercial freight, ranging from hundreds of cases of wine to bales of rubber, cork, and raw silk, many of the passengers entrusted the vessel to carry across the ocean some of their most costly possessions. First-class passenger and survivor William E. Carter, who initially booked passage for himself and his family on the RMS Olympic before deciding to instead leave on the later RMS Titanic, brought on the voyage his 1912 Renault Type CB Coupe de Ville, which was stored in the forward hold of the ship; for fans of the 1997 movie Titanic, the car makes an appearance in Jack and Rose’s steamy rendezvous below deck. The value of the car was estimated to be $5,000, or roughly $150,000 in today’s money.

A number of irreplaceable books were also lost in the sinking of the Titanic, including a rare 1598 copy of Francis Bacon’s essays and a lavishly custom bound edition of Omar Khayyam’s Rubaáyyát. The Rubaáyyát volume had a bespoke binding that spared no expense, featuring a cover of Moroccan leather inlayed with gold and ivory, and over 1,000 precious and semiprecious stones. It was at the time the most expensive book binding ever created.

The most valuable single item onboard the Titanic was, however, a 1912 painting by Merry-Joseph Blondel, La Circassienne au bain. Based on the insurance claim made after the fact, the work was estimated to be $100,000, equivalent to just over $3 million dollars today. The painting belonged to Swedish businessman Mauritz Håkan Björnström-Steffansson, who survived by jumping into the vacant bow of one of the last lifeboats. His claim against White Star Line, the British shipping company that operated the Titanic, was the largest single article claim for either personal or commercial loss.

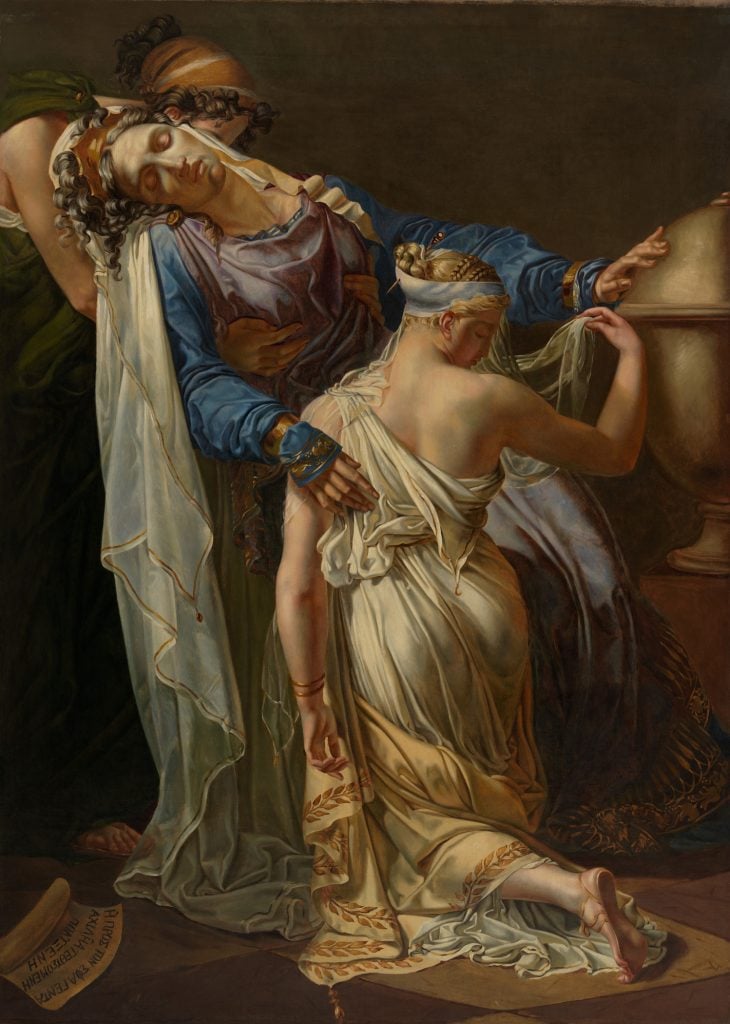

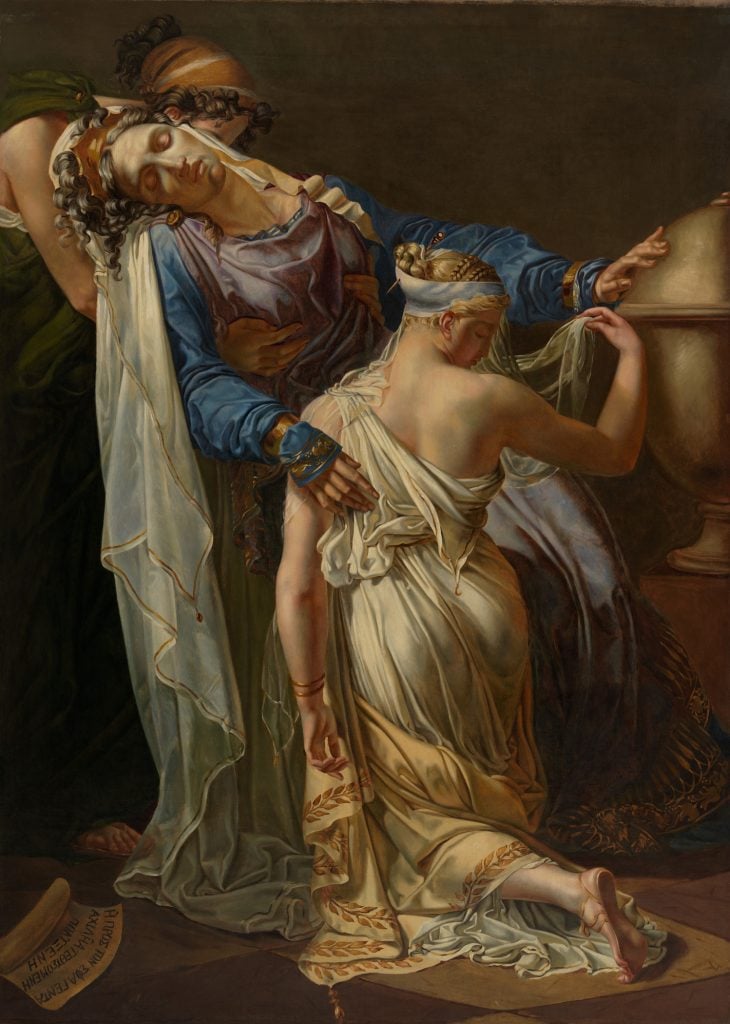

Merry Joseph Blondel, Hecuba and Polyxena (after 1814). Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

But what made this single painting so valuable? What did it look like, and who was the artist that painted it? We took a deep dive to find out more about the most expensive artwork lost on the RMS Titanic.

Who was Merry-Joseph Blondel?

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Merry-Joseph Blondel (1809). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Though his name is not widely recognizable today, French Neoclassical painter Merry-Joseph Blondel was a well-known and awarded figure within the 19th century art scene. Born in 1781, Blondel hailed from an artistic family; his father, Joseph-Armand Blondel, was a successful painter who also specialized in stucco (or render) decoration. Following a series of unsuccessful apprenticeships his father committed him to, Blondel eventually became a student of French painter Jean-Baptiste Regnault in 1801.

Although he achieved early recognition for his work while under the tutelage of Regnault, it was in 1803 when he was awarded the Prix de Rome for his painting depicting the mythical hero Aeneas carrying his father Anchises from the burning city of Troy that his career took off. The award secured a place for Blondel at the French Academy in Rome at the Villa Medici, however, due to bureaucratic technicalities, it was not until 1809 that he enrolled. Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres was a fellow student, and though their respective teachers were rivals (Blondel with Regnault, Ingres with Jacques Louis David), and they frequently competed for the same positions and awards, they remained lifelong friends.

Merry-Joseph Blondel, Aeneas rescuing his father Anchises from the burning Troy (ca. 1803).

Ultimately, Blondel returned to Paris in the early 1810s, and began to regularly contribute to the salon exhibitions at the Louvre Museum. Blondel’s work was heavily influenced by Neoclassicism, a style that exploded in popularity in the late 18th century and remained fashionable throughout the early 19th century. Focusing on classical themes and subjects, and employing clean, often austere compositional tactics, Neoclassical painting was an apogee of traditional academic painting styles, emphasizing skill, technique, and restraint. Blondel excelled in the style and won several awards and medals for his work, as well as received numerous prominent public commissions, including notably the fresco cycle The Fall of Icarus (1819) at the Louvre and a series of full-length royal portraits for the Palace of Versailles.

Merry-Joseph Blondel, The Fall of Icarus (1819). Collection of the Louvre Museum, Paris.

In 1824, King Charles X of France elevated him to the rank of Knight of the Royal Order of the Legion of Honor, and he was given a seat within the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1832. Contemporaneously to his knighting, Charles X also offered him a teaching position at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, which he took and remained at until his death in 1853.

La Circassienne au Bain (1814)

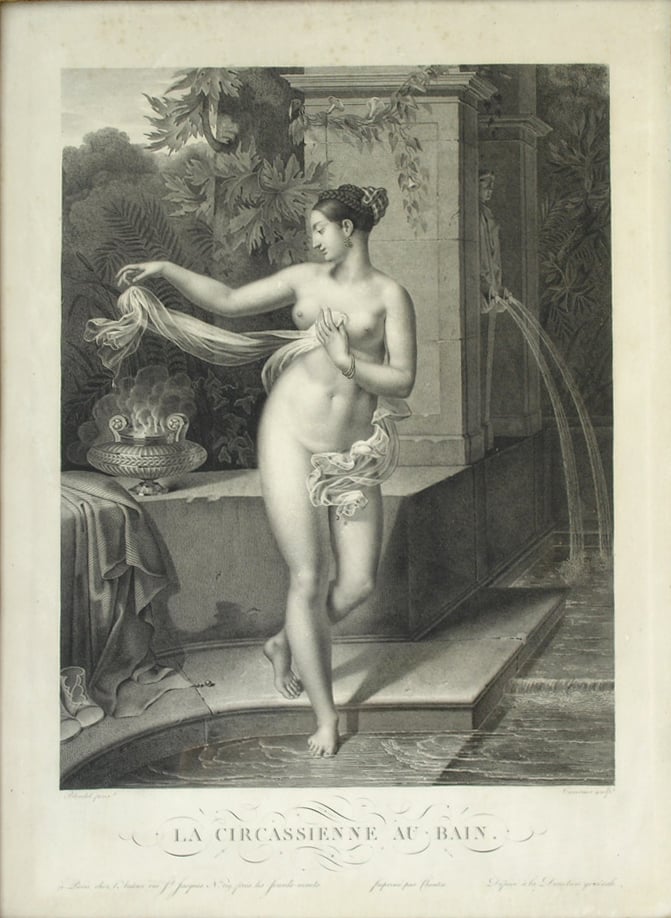

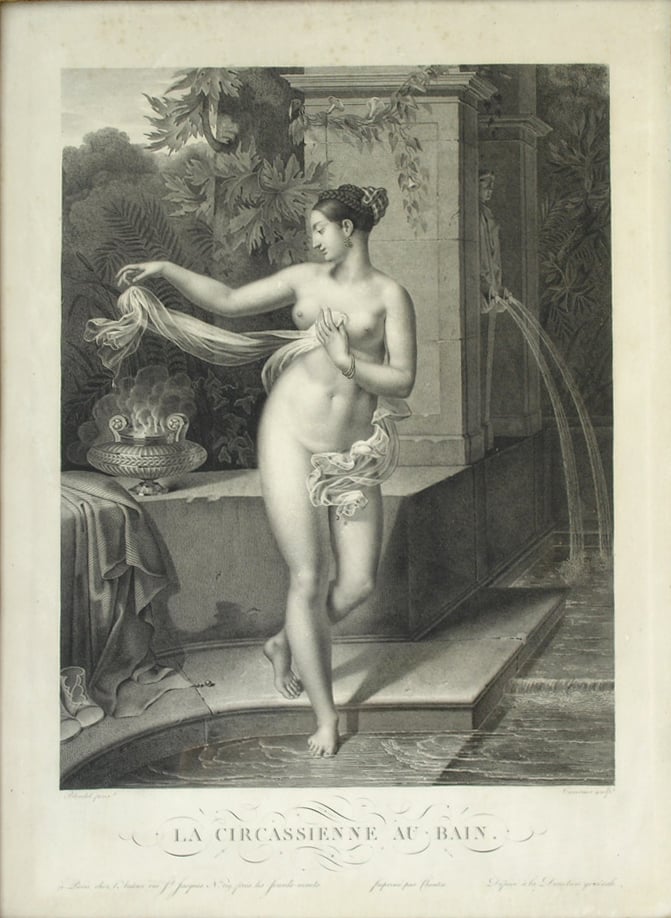

Pierre-Joseph Tavernier, after Merry-Joseph Blondel, La Circassienne au Bain (1814).

Blondel’s La Circasienne au Bain of 1814, sometimes referred to as Une Baigneuse, is emblematic of the Neoclassical style. Featuring a full-length portrait of an idealized Circassian woman stepping into a bath inspired by those of classical antiquity, Blondel completed the work within only a few years of his return to Paris. It was exhibited at the Paris Salon at the Louvre Museum the same year it was finished, and the initial reception of the work seems to have been decidedly reserved. While the work illustrated Blondel’s technical skill, it lacked the artist’s usual artistic nuance and dynamism.

Despite the loss of the original, lithographic reproductions from French and German periodicals illustrate the somewhat stilted, highly stylized composition. Though strictly adhering to the tenants of Neoclassicism, the work lacks a general sense of grace or natural movement. Over the course of the next century, however, as Blondel became more famous, the work seemingly garnered more favor as its value skyrocketed.

John Parker, after Merry-Joseph Blondel, La Circassienne au Bain (date unknown).

According to the insurance claim made by Björnström-Steffansson for the painting following its loss aboard the Titanic, it stood at approximately eight feet tall and four feet wide—though this has been contested, as it does not correlate with the scale that Blondel typically worked in outside of frescoes, or with size of full-length portraits of the period. An anonymous artist going by the sobriquet John Parker conducted extensive research and reproduced the work in color in oil on canvas sometime in the early 2010s, giving insight into what the original may have looked like.

When or where Björnström-Steffansson initially acquired La Circasienne au bain is unknown. Following his studies at the Stockholm Institute of Technology, where he focused on chemical engineering, he was enroute to Washington, D.C., to continue his studies on a scholarship awarded by the Swedish government when he boarded the Titanic. It could be inferred that he perhaps brought it with him on the voyage as something to ultimately help furnish his accommodations; or, alternatively, he may have brought it as capital in case of need.

The Aftermath

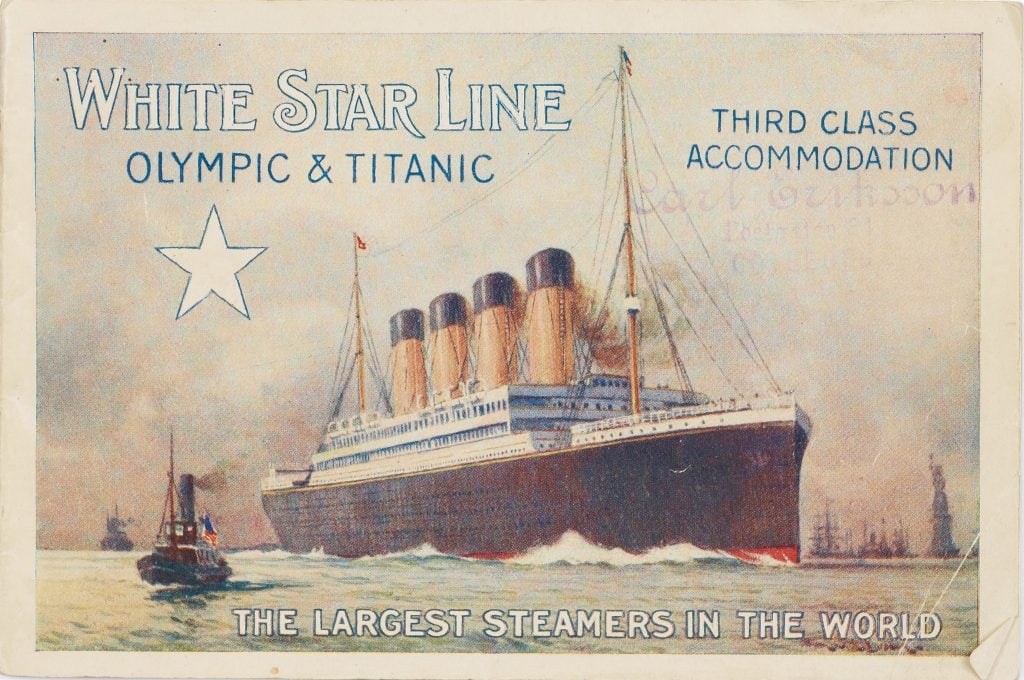

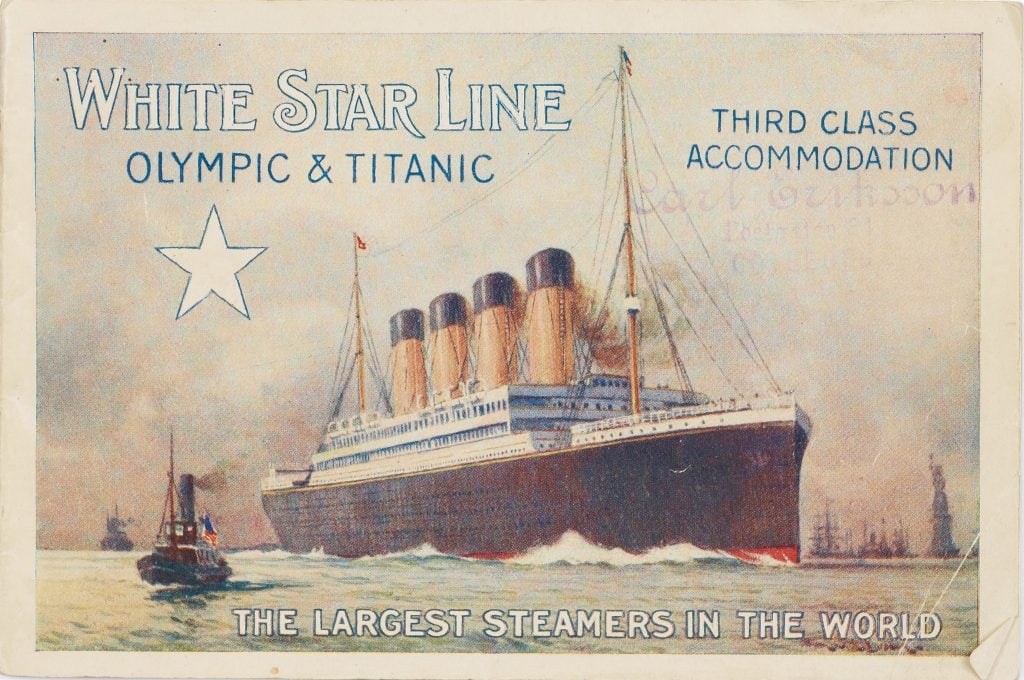

White Star Line. Titanic and Olympic, ca. 1910. From a private collection. Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images.

On August 22, 1913, the New York Times reported that the total aggregated claims brought against the Titanic’s operator Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, Ltd. (White Star Line) had reached $16,804,112.23 (equivalent to over half a billion today)—an incredible sum comprised of loss of life, personal injury, and loss of property claims. What was lost on the Titanic can largely be deduced through the formal claims made by passengers, however, it is possible that there were more artworks and artefacts lost that were not claimed because their owners perished. Some that survived may have only made claims for what they felt was most valuable, such as jewelry and wardrobes full of haute couture, while others are known to have made wide ranging claims—right down to the cost of a bar of soap.

It is unknown how much Björnström-Steffansson’s claim for Blondel’s La Circasienne au Bain was settled for, but in total we know that following negotiations the total settlement paid out was $644,000, or approximately $19.6 million today. Ironically, the loss of Blondel’s 1814 painting has helped to keep his name and his practice alive over the centuries, as with each anniversary of the Titanic’s fateful first and last voyage La Circasienne au Bain is brought to light once more as the single most expensive item to go down with the ship.