Art World

A Former Janitor at a Migrant Detention Center Has Turned Items Confiscated From Detainees Into Art

Tom Kiefer secretly rescued belongings destined for the trash, photographing them to honor their former owners.

Tom Kiefer secretly rescued belongings destined for the trash, photographing them to honor their former owners.

Maxwell Williams

The desert along the Mexico-US border is a treacherous place. People with no other options, escaping difficult situations often produced by U.S. intervention in their homelands, travel shocking distances in search of a better life. And then, if they’re lucky enough to survive, they are often captured by US border agents, processed, and deported. “El Sueño Americano | The American Dream: Photographs by Tom Kiefer,” a new show at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, hones in on a step in that unforgiving process.

Tom Kiefer yearned to photograph grain silos and billboards—“the American landscape,” he calls it—like his heroes Walker Evans, Robert Frank, and Frank Gohlke. But his idea of the American landscape, and the focus of his lens, changed after taking a job as a custodian at the US Customs Border Protection processing center a few miles outside of the small southwestern Arizona town of Ajo, where he lives.

© Tom Kiefer, Cynthia’s CD Collection (2017). Courtesy of Redux Pictures.

There, he began collecting objects confiscated from apprehended migrants and discarded in the trash that it was his job to take out. Kiefer eventually figured out ways to photograph the belongings as a way to honor their former owners.

In the early 2000s, Kiefer had moved from L.A. to the small former copper mining community of Ajo in the Sonoran Desert, so he could achieve his goal of becoming a homeowner, something that had proven impossible in Los Angeles. He took a job as a janitor, because “art doesn’t pay the bills,” he tells me over the phone from his home in Ajo, about 40 miles or so from the Mexican border.

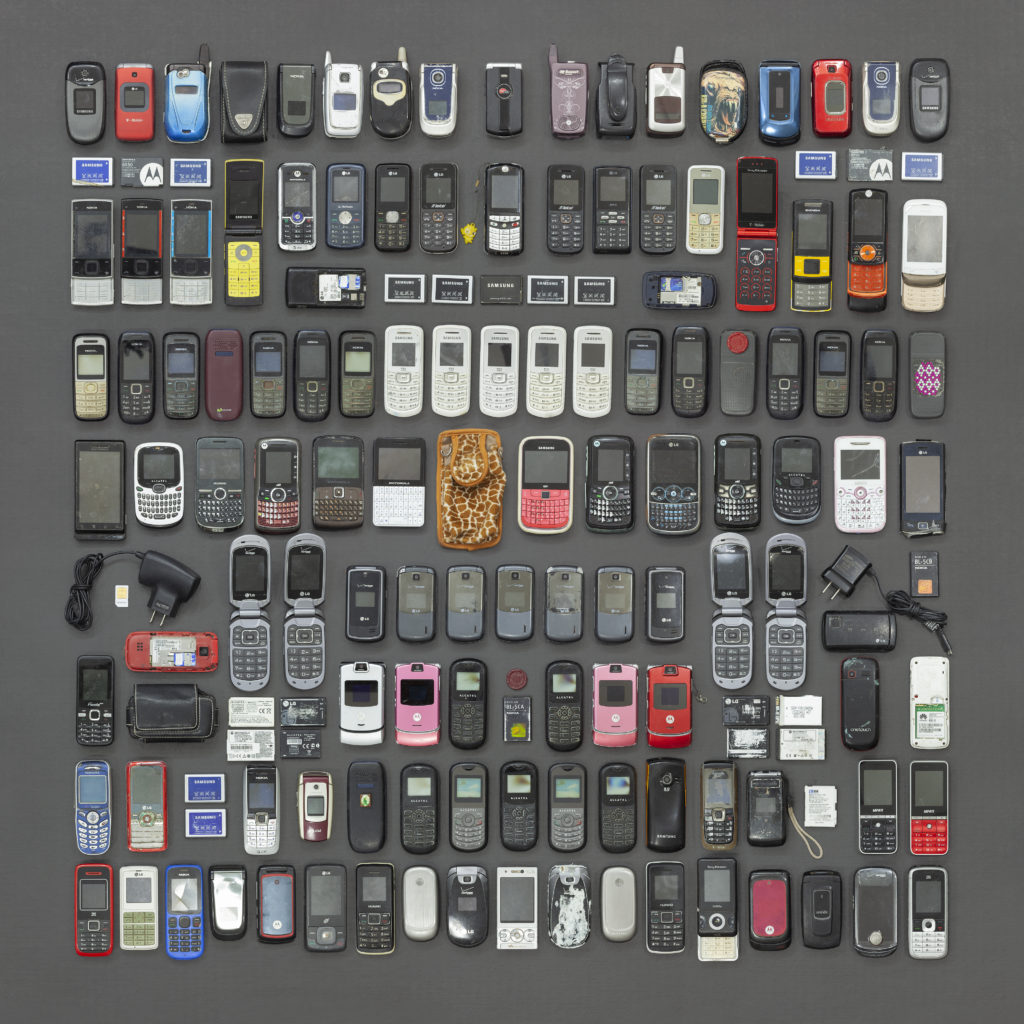

© Tom Kiefer, Cell Phone Assembly (2019). Courtesy of Redux Pictures.

Kiefer went in every day to the processing center and did his job until 2014. Moving through the space as a janitor, he could blend in, and he became almost a fly on the wall, able to see the entire operation. Vehicles would pull into the sally port—a small fenced-in docking station—of the center, and out would step people who had crossed the Mexico-US border, risking it all to seek a better life in America before being picked up by CBP officers.

“The people that had been apprehended in the desert would pile out, and then that’s where they would start the first stages of processing,” Kiefer recalls. “First, either the agent or the person apprehended go through the backpacks [full of belongings that the migrants had been carrying with them through the desert]. They basically empty just about everything in the backpack because they aren’t allowed extra shoes or clothing they brought with them, or belts or shoelaces or toiletries; anything considered nonessential or potentially lethal was confiscated and thrown in the trash.”

© Tom Kiefer, Tuny (2015). Courtesy of Redux Pictures.

At first, Kiefer noticed that there was quite a bit of non-perishable food being thrown out—stuff that needed to last the trek through the desert—and in 2007, he asked his supervisor if he could bring the items to a food bank. The supervisor acquiesced and Kiefer started going through the bags to pull out food. But one day he noticed another item in among the bags: a rosary, and other personal items.

“And I thank God that I just listened to my heart and my head, and said, ‘No, I can’t, I can’t let this rosary stay in the trash, or this Bible, or this family photograph,’” Kiefer recalls thinking. “’This just ain’t right.’”

So he began to clandestinely swipe things destined for the garbage. He would stash them at home in boxes, organized by object—toothbrushes in one box, rosaries in another, kids’ shoes in one, medication in another.

“What I recovered was such a small portion [of the objects confiscated from the migrants],” Kiefer says. “I was there to empty trash. I couldn’t stand around above a dumpster or garbage can—everything was a split-second decision. And I couldn’t draw any attention to myself.”

© Tom Kiefer. Pain Relief (2017). Redux Pictures.

For six years, Kiefer continued to his collection, not knowing exactly what he was going to do with it all. He didn’t want to create false, staged narratives by placing the objects in a desert setting, as if they had been left behind. Finally, he realized that he could use color and type to bring the objects to life. He photographed black combs on a black background and pink combs on pink backgrounds; arranged toothbrushes in an almost ironic red, white, and blue; and placed rosaries together against a vibrant red backdrop. For Kiefer, the images are a reminder that the people were here, and that they aren’t forgotten.

“Where I always come from is a place of deep reverence and respect towards these belongings that were taken away from people,” says Kiefer. “I use color to, not to doll it up or make it pretty, but just to make it beautiful—give it its rightful moment in the sun, so to speak.”

Installation view of “El Sueno Americano” at the Skirball Cultural Center.

Kiefer sees his images as documents of a dark period of American history, one that he thinks will be remembered with shame.

“One of the things that I want this work to accomplish is just for people to think for themselves, about what is our country becoming?,” he says. “Is this how we want to treat the most vulnerable? I mean, we’re not talking about terrorists, for God’s sake. You take away a Bible and a rosary. How is that protecting the border?”