People

Why Tourmaline, Chronicler of Queer and Trans Histories, Has Devoted Her Debut Solo Show to Self-Portraits of Fantastic Pleasure

For her debut exhibition at Chapter NY, Tourmaline places herself at the center of tableaux about pleasure.

For her debut exhibition at Chapter NY, Tourmaline places herself at the center of tableaux about pleasure.

Jessica Lynne

To encounter the work of filmmaker and artist Tourmaline is to encounter the work of a person who is enthralled by a meticulous chronicling of history.

This is one of the first things that crosses my mind as I listen to Tourmaline speak about the research processes that she employs in order to tell the stories of Black trans and queer people who have long shaped our world.

Hers is a relationship to Black histories that began as a young person growing up in a family of activists and organizers. While in high school, she started a Black history class—and it was soon offered as an elective to other students. As her interests drew her to New York City and further into activism, this belief in the potency of history only strengthened.

“My fascination and love and life-affirming feelings for the history of our community started as a very young age as a way to ground myself in my power,” she tells me.

Tourmaline is an artist who organizes. She is an artist wrestling with conditions of Black freedoms. She is an artist who chooses to see all that hides in plain sight.

Tourmaline, Salacia (2019). Courtesy of Chapter, NY.

This ethos of discovery pervades an oeuvre that captures on-screen truths about the lives of women such as the late activist, educator, and performer Marsha P. Johnson, Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, and most recently, Mary Jones, a Black trans woman and sex worker who lived in Seneca Village. (The 19th-century community was one of the first areas in New York City where Black freed men were able to own land; it was later destroyed to build Central Park.)

Jones’s story anchors Tourmaline’s most recent short film, Salacia. And it is this film that informs and inspires a new series of self-portraits that comprise the artist’s first solo show, “Pleasure Garden,” on view at Chapter NY Gallery through January 31.

Taking Salacia as a source, the photographs in the exhibition speak directly to a central tenet of Tourmaline’s practice: pleasure.

In the early 1800s, pleasure gardens were best known as public venues that provided fantastical bouts of leisure for wealthy, white New Yorkers. In turning the camera on herself, Tourmaline places herself in conversation with the Black pleasure grounds of the same era that offered respite to Black workers and families living in lower Manhattan.

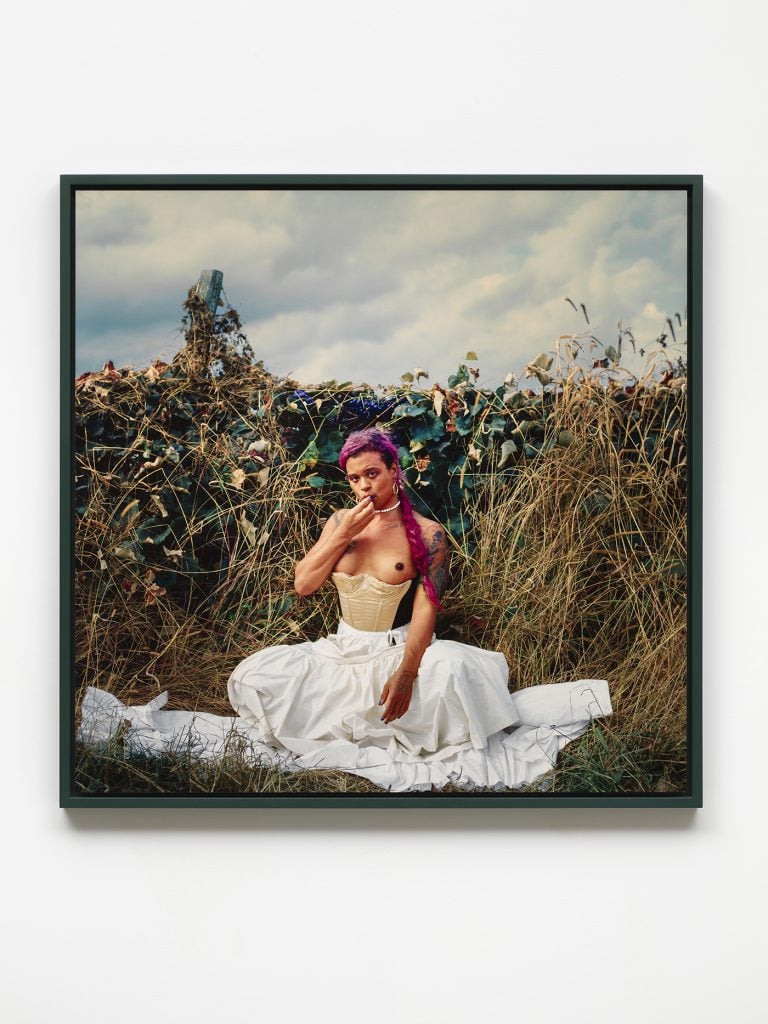

Tourmaline, Morning Cloak (2020). Photo: Dario Lasagni, courtesy of Chapter NY.

In Morning Cloak, Tourmaline, 37, sits on the grass in a pleasure garden of her own divination. She wears a white outfit that is gathered at the waist, flowing outward from her body, and a tan bustier. She gazes at the camera slyly while eating a grape. Summer Azure captures the artist suspended in the blue sky, wearing a helmet designed for space travel, as if to say, “Here, too, I will bask in the sweetness of myself.”

These photographs take their visual cues from research that Tourmaline conducted for the film, pouring over archives about Seneca Village, analyzing ambrotypes of the Lyons family (one of the first families to own land in the village), and closely examining the photography of Jacob Riis, who documented the conditions of tenement housing of Manhattan.

Still, the artist was most curious about what it would have meant for Black folks to have imaged themselves. That became her anchoring prompt and invitation into the world of “Pleasure Garden.”

Self-portraiture represents a new medium for the artist, but it is the form that allowed Tourmaline to include herself in this ongoing act of freedom dreaming that has become so central to her filmmaking.

Her first film, The Personal Things, an animated short based on the life of Miss Major, was released in 2016. But it is her previous work at organizations such as the Sylvia Rivera Law Project and Queers for Economic Justice and her role as a longtime organizer that propelled her research of the Black and brown trans histories that ground her art practice.

“I am always working to expand my practice and so one thing that I had noticed is that I had yet to incorporate myself on the other side of the lens,” Tourmaline says. “I had to sit with that and the idea that if we are talking about all of us as a community, for me, at least, it’s really important to not leave myself out.”

If there was a discomfort in this approach, it is difficult to assess from the photographs. An affirming mood of ease pervades them. In Coral Hairstreak, she stands in a cornfield wearing the same white outfit she donned in the air. She holds onto her sunglasses with her left hand, gazing directly at the camera. This is nothing if not certainty.

Tourmaline, Coral Hairstreak (2020). Photo: Dario Lasagni, courtesy of Chapter NY.

“The generous seduction within Tourmaline’s artistic practice is that her work offers us an occasion to practice and experience the pleasures of the kinds of worlds in which we as queer and trans Black and brown people want to live,” says Thomas Lax, the curator of media and performance at the Museum of Modern Art, which acquired Salacia last year. “By folding the past, present, and future in on themselves, she offers all of us a lush and generative space in which we can offer a fleshy record of what has been as we insist on making good on our most wild desires.”

Indeed, pleasure lives in this “fleshy record.” It lives in the proclamation that names that which has always been here, that is still here with us. Through Tourmaline’s eyes, we witness histories generated by individuals who seek sites of liberation beyond the conscriptions of dominant discourse. We are encouraged to take pleasure in the imagining of an otherwise because we are not the first to do so.

“Now I’m kind of like, look at the presence,” she says. “Look at the presence of Marsha [P. Johnson]. I don’t need to convince anybody about the power and the beauty of a Miss Major or a Marsha. I, as an artist, am just going to bask in and share my joy in relationship to these stories, to these places. In doing that, I get to benefit from the real power of people who came before me.”